Pregnancy in women with autoimmune rheumatic diseases is associated with several maternal and foetal complications. The development of clinical practice guidelines with the best available scientific evidence may help standardize the care of these patients.

ObjectivesTo provide recommendations regarding prenatal care, treatment, and a more effective monitoring of pregnancy in women with lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS).

MethodologyNominal panels were formed for consensus, systematic search of information, development of clinical questions, processing and grading of recommendations, internal validation by peers, and external validation of the final document. The quality criteria of the AGREE II instrument were followed.

ResultsThe various panels answered the 37 questions related to maternal and foetal care in SLE, RA, and APS, as well as to the use of antirheumatic drugs during pregnancy and lactation. The recommendations were discussed and integrated into a final manuscript. Finally, the corresponding algorithms were developed. We present the recommendations for pregnant women with SLE in this first part.

ConclusionsWe believe that the Mexican clinical practice guidelines for the management of pregnancy in women with SLE integrate the best available evidence for the treatment and follow-up of patients with these conditions.

El embarazo en mujeres con enfermedades reumáticas autoinmunes se asocia a diversas complicaciones maternofetales. El desarrollo de guías de práctica clínica con la mejor evidencia científica disponible puede ayudar a homogeneizar la atención en estas pacientes.

ObjetivosProporcionar recomendaciones respecto al control prenatal, el tratamiento y el seguimiento más efectivo de la mujer embarazada con lupus eritematoso (LES), artritis reumatoide (AR) y síndrome por anticuerpos antifosfolípidos (SAF).

MetodologíaPara la elaboración de las recomendaciones se conformaron grupos nominales de expertos y se realizaron consensos formales, búsqueda sistematizada de la información, elaboración de preguntas clínicas, elaboración y calificación de las recomendaciones, fase de validación interna por pares y validación externa del documento final teniendo en cuenta los criterios de calidad del instrumento AGREE II.

ResultadosLos grupos de trabajo contestaron las 37 preguntas relacionadas con la atención maternofetal en LES, AR y SAF, así como de fármacos antirreumáticos durante el embarazo y la lactancia. Las recomendaciones fueron discutidas e integradas en un manuscrito final y se elaboraron los algoritmos correspondientes. En esta primera parte se presentan las recomendaciones para mujeres embarazadas con LES.

ConclusionesLa guía mexicana de práctica clínica para la atención del embarazo en mujeres con LES proporciona recomendaciones e integra la mejor evidencia disponible para el tratamiento y el seguimiento de estas pacientes.

Autoimmune diseases develop more frequently in women in reproductive stage; thus, during pregnancy their development is potentially frequent. Pregnancy requires the interaction of endocrine and immune mechanisms, which facilitate maternal and foetal communication, regulate implantation, foster placental growth and prevent immune rejection of the semialogenic foetus.1 These changes can affect the clinical course of autoimmune diseases and they can in turn have an influence on the maternal and foetal outcome, so these are considered high-risk pregnancies.2 The type and frequency of maternal and foetal complications vary with each autoimmune disease.2 However, in general terms, the risk of an adverse maternal and foetal outcome can be reduced when the pregnancy is planned, especially when the disease is controlled and minimal risk medications can be used during gestation. Thus, a multidisciplinary team that participates in the health care process of this group of patients and contributes to the improvement of the maternal and foetal outcome is required.

Pregnancy in women with autoimmune rheumatic disease, especially in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), means a significant challenge for the physicians in charge of the health care process of this group of patients. Knowledge about the security of medications, the effect of pregnancy on the disease, the effect of the disease on pregnancy, preconception advice and the participation of a multidisciplinary team are cornerstones for the provision of effective and safe medical and obstetrical attention. A planned pregnancy associated to close obstetric surveillance during the entire pregnancy and the puerperium increase the probability of favourable outcomes in the mother-son pairing.

The development of a clinical practice guideline (CPG) for pregnancy and autoimmune rheumatic diseases derives from the need to provide recommendations supported by the best scientific evidence available to the health care professional in charge of this group of patients, aiming at minimizing the frequency of maternal and foetal complications. In this first part of the CPG, its development and methodology as well as the recommendations for women with SLE are shown.

Extent and Objectives- •

To provide recommendations about prenatal control, the most effective treatment and follow-up of pregnant women with SLE, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS).

- •

To prevent the main maternal and foetal complications in women with autoimmune rheumatic diseases.

- •

To identify and reduce the risk of foetal adverse reactions and events related to the use of antirheumatic drugs in women with autoimmune rheumatic diseases.

This guideline is targeted to rheumatologists, OB/GYNs, internists and neonatologists.

Target PopulationWomen ≥18 years old with an established diagnosis of SLE, RA and APS.

Attention LevelSecond and third attention level. The use of this guideline will improve the efficacy, security and quality of the medical attention provided to the target population.

MethodologyThe methodology used in the preparation of the document included the establishment of nominal groups of experts, development of formal consensus, search for systematized information, elaboration of clinical questions, elaboration and qualification of recommendations, internal validation phase by pairs and external validation of the final document. During the elaboration of the guideline, the quality criteria of AGREE II3 instrument were considered.

Working Group. For the establishment of the working group, 30 rheumatologists who are members of the Colegio Mexicano de Reumatología (Mexican College of Rheumatology) where invited and 2 of them rejected the invitation to participate. The selection process considered the professional background of the experts, their clinical judgement, the geographical diversity (with reasonable representation of the different states of the country), their belonging to the main health institutions in the country, including second and third attention level institutions, knowledge and command of the subject, representation per gender, with a men-women balance in the working tables, as well as training in the development of CPG with evidence-based medicine methodology. Given the importance of creating a multi and interdisciplinary working group, apart from the presence of rheumatologists, the collaboration of other specialists was requested so as to obtain their opinion to help improve the disease treatment or the methodology of recommendations elaboration. Finally, the group was made up of 23 rheumatologists, 2 internists, one paediatric neonatologist and 2 OB/GYNs. Once all the members of the working group were selected, and upon their agreement to participate in the project, a nominal group meeting was convened. In this meeting, a theoretical explanation of the CPG working methodology was carried out and a debate was opened to define the title, extent, objectives and users of the guideline; the leaders of each working table were appointed. In the working group training, the development of the PICO (patient, intervention, comparator and outcome or result) clinical questions, CPG elaboration and adaptation, evidence and recommendations elaboration and qualification as well as search protocol procedures were addressed. The working groups reviewed the following subjects: (1) SLE I (maternal morbidity), (2) SLE II (foetal morbidity), (3) RA, (4) APS, and (5) use of antirheumatic drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Development of RecommendationsThe recommendations developed in this document are general in nature and based on the best scientific evidence available at the moment of their development; they pretend to be a useful tool to accelerate the decision-making during the health care process of the pregnant patient with SLE, RA and APS. In this way, the recommendations established herein do not define a unique course of behaviour in a procedure or treatment; thus, when applied in practice, they could exhibit justified variations based on the clinical judgement of the person using them as reference, as well as on the specific needs and preferences of each patient in particular, the resources available at the time of attention and the regulation established by each institution or practice area.

Systematic Search. The systematic search for information was focused on CPG and on primary and secondary studies about SLE, RA, primary APS and antirheumatic drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

The CPG search was carried out in web sites belonging to entities in charge of the elaboration and compilation of CPG. Below, there is a table that shows the web sites consulted for the preparation of this guideline (Table 1).

Websites Consulted for the Elaboration of This CPG Guideline.

| Websites | No. of results obtained | No. of documents used |

|---|---|---|

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) – England | 7 | 0 |

| Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) – Scotland | 3 | 0 |

| New Zealand Guidelines Group (NZGG) – New Zealand | 0 | 0 |

| National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) – Australia | 1 | 0 |

| Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) health care guidelines – USA | 0 | 0 |

| National Guideline Clearinghouse | 6 | 0 |

| Guidelines International Network (G-I-N) | 15 | 0 |

| Total | 32 | 0 |

As no CPG addressed clinical questions related to potential pregnancies during the course of the 3 target rheumatic diseases, it was not possible to develop the guideline through the adaptation process. For that reason, we proceeded with the de novo elaboration, and carried out a search for primary and secondary studies in Pubmed, Tripdatabase and the Cochrane library, based on the following inclusion criteria:

- •

Documents written in English and Spanish.

- •

Documents published during the last 5 years (recommended range) or, in case of scarce or null information, documents published during the last 10 years (extended range).

- •

Documents focused on treatment.

The bibliographical search was carried out during June 2013 and the terms MeSH Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic AND pregnancy were employed. The search protocol used was: (“Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic/complications”[Mesh] OR “Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic/congenital”[Mesh] OR “Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic/drug therapy”[Mesh] OR “Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic/pharmacology”[Mesh] OR “Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic/prevention and control”[Mesh] OR “Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic/therapy”[Mesh]) AND (“pregnancy”[MeSH Terms] OR “pregnancy”[All Fields]) AND ((Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Comparative Study[ptyp] OR Consensus Development Conference, NIH[ptyp] OR Controlled Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Guideline[ptyp] OR Meta-Analysis[ptyp] OR Multicenter Study[ptyp] OR Observational Study[ptyp] OR Practice Guideline[ptyp] OR Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp] OR Review[ptyp] OR systematic[sb]) AND “2004/04/27”[PDat]: “2013/09/24”[PDat] AND “humans”[MeSH Terms] AND (Spanish[lang] OR English[lang])). 110 results were found.

The bibliographical search for RA employed the MeSH terms: Arthritis, Rheumatoid AND pregnancy. The search protocol used was: (“Arthritis, Rheumatoid/complications”[Mesh] OR “Arthritis, Rheumatoid/congenital”[Mesh] OR “Arthritis, Rheumatoid/drug therapy”[Mesh] OR “Arthritis, Rheumatoid/embryology”[Mesh] OR “Arthritis, Rheumatoid/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Arthritis, Rheumatoid/prevention and control”[Mesh] OR “Arthritis, Rheumatoid/therapy”[Mesh]) AND (“pregnancy”[MeSH Terms] OR “pregnancy”[All Fields]) AND ((Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Comparative Study[ptyp] OR Controlled Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Guideline[ptyp] OR Multicenter Study[ptyp] OR Observational Study[ptyp] OR Practice Guideline[ptyp] OR Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp] OR Review[ptyp] OR systematic[sb]) AND “2004/04/27”[PDat]: “2013/09/24”[PDat] AND “humans”[MeSH Terms] AND (English[lang] OR Spanish[lang])). 51 results were found.

The bibliographical search for APS used the MeSH terms: Antiphospholipid Syndrome AND pregnancy. The search protocol used was: (“Antiphospholipid Syndrome/complications”[Mesh] OR “Antiphospholipid Syndrome/congenital”[Mesh] OR “Antiphospholipid Syndrome/drug therapy”[Mesh] OR “Antiphospholipid Syndrome/embryology”[Mesh] OR “Antiphospholipid Syndrome/genetics”[Mesh] OR “Antiphospholipid Syndrome/mortality”[Mesh] OR “Antiphospholipid Syndrome/prevention and control”[Mesh] OR “Antiphospholipid Syndrome/therapy”[Mesh]) AND (“pregnancy”[MeSH Terms] OR “pregnancy”[All Fields]) AND ((Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Comparative Study[ptyp] OR Controlled Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Guideline[ptyp] OR Meta-Analysis[ptyp] OR Multicenter Study[ptyp] OR Observational Study[ptyp] OR Practice Guideline[ptyp] OR Review[ptyp] OR systematic[sb]) AND “2004/04/27”[PDat]: “2013/09/24”[PDat] AND “humans”[MeSH Terms] AND (English[lang] OR Spanish[lang])). 246 results were found.

The search protocol related to antirheumatic drugs security in women with autoimmune rheumatic diseases was as follow: (“antirheumatic agents”[Pharmacological Action] OR “antirheumatic agents”[MeSH Terms] OR (“antirheumatic”[All Fields] AND “agents”[All Fields]) OR “antirheumatic agents”[All Fields] OR (“antirheumatic”[All Fields] AND “drugs”[All Fields]) OR “antirheumatic drugs”[All Fields]) AND (autoimmune[All Fields] AND (“rheumatic diseases”[MeSH Terms] OR (“rheumatic”[All Fields] AND “diseases”[All Fields]) OR “rheumatic diseases”[All Fields])) AND ((Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Comparative Study[ptyp] OR Controlled Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Meta-Analysis[ptyp] OR Multicenter Study[ptyp] OR Observational Study[ptyp] OR systematic[sb]) AND “2004/04/27”[PDat]: “2013/09/24”[PDat] AND “humans”[MeSH Terms] AND (English[lang] OR Spanish[lang])). 96 results were found. Out of the 503 articles obtained in the search protocols, 346 articles were excluded based on the reading of their titles and abstracts, as they did not comply with the objectives of the questions raised in this guideline.

Upon the search for information, a total of 157 articles were selected for the elaboration of the document. The articles were referred to the experts’ panel for their critical reading and assessment of the evidence degree. For the grading of level of evidence, Shekelle et al.4 Classification System was employed. This classification lets us estimate the strength of the recommendations and assess the evidence quality based on the best design to answer the question (Table 2). The aspects considered significant by the editorial team of the guideline because they make up an area lacking conclusive evidence or because they are specially relevant clinical aspects, were marked with the sign (√) and received the consideration of good practice point (GPP) or opinion based on clinical experience and reached through consensus.

Shekelle et al. Modified Scale.

| Evidence category | Recommendation soundness |

|---|---|

| Ia. Evidence for meta-analysis of the randomized clinical studies | A. Directly based on category I evidence |

| Ib. Evidence from at least one randomized controlled clinical study | |

| IIa. Evidence from at least one controlled study without randomization | B. Directly based on category II evidence or recommendations extrapolated from evidence I |

| IIb. At least other kind of quasi-experimental study or studies of cohort | |

| III. Evidence of a descriptive, non-experimental study, such as comparative studies, correlation studies, cases and controls and clinical reviews | C. Directly based on category III evidence or recommendations extrapolated from category I or II evidences |

| IV. Evidence from expert's committees, reports, opinions or clinical experience from authorities regulating the subject or both | D. Directly based on category IV evidence or recommendations extrapolated from category IIor III evidences |

It classifies evidence per levels (categories) and indicates the source of the issued recommendations based on the soundness degree. To establish the evidence category, it uses Roman numbers from i to iv and letters a and b (lower case). In soundness of recommendation, upper case letters from A to D are used.

Source: Modified from Shekelle et al.4

Validation method: Clinical pairs.

Update period: This guideline shall be updated when there is evidence supporting its update or, if previously scheduled, 3–5 years after its release.

Questions IncludedSystemic Lupus Erythematosus- 1.

In women with SLE, which are the safest contraceptive options?

- 2.

In women with SLE, what actions shall be implemented during the preconception period?

- 3.

In pregnant women with SLE, what are the frequency and risk factors of disease relapse?

- 4.

In pregnant women with SLE, what are the frequency and risk factors to develop preeclampsia/eclampsia?

- 5.

In pregnant women with SLE, which are the most effective treatment options to prevent and treat disease reactivation?

- 6.

In pregnant women with SLE, what are the frequency and risk factors associated to foetal loss?

- 7.

In pregnant women with SLE, what are the frequency and risk factors associated to preterm birth?

- 8.

In foetus of pregnant women with SLE, what are the frequency and risk factors associated to low birth weight/intrauterine growth restriction/small for gestational age?

- 9.

In women with SLE, how is the follow-up during pregnancy and immediate puerperium carried out?

- 10.

In foetus of women with positive anti-Ro and/or anti-La antibodies, what are the most effective prevention and treatment options for the management of congenital heart block (CHB)?

- 11.

In women with RA, which is the disease effect and treatment regarding fertility and fecundity?

- 12.

In women with RA, which are the most effective contraceptive options?

- 13.

In women with RA, which are the safest contraceptive options?

- 14.

In women with RA, which is the disease improvement or relapse frequency during pregnancy and puerperium?

- 15.

In women with RA, which are the factors associated with the disease improvement or relapse during pregnancy and puerperium?

- 16.

In pregnant women with RA, which is the best instrument to assess the disease activity?

- 17.

In pregnant women with RA, what is the gestation effect on the clinical instruments of functional assessment?

- 18.

In pregnant women with RA, what is the effect of antibodies (rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies) on the disease activity?

- 19.

In pregnant women with RA, which is the influence of the disease activity on the foetal outcome?

- 20.

In pregnant women with RA, which are the safest treatment options to manage a reactivation of the disease?

- 21.

In breastfeeding women with RA, which is the effect on the disease activity?

- 22.

In women with APS, which are the safest contraceptive options?

- 23.

In women with APS, which are the actions and procedures that should be implemented during the prenatal control?

- 24.

In pregnant women with APS, what are the risk factors for the development of preeclampsia?

- 25.

In pregnant women with APS, with a history of 3 or more miscarriages (≤10 weeks of gestations [WOG]) and without previous history of thrombosis, what are the most efficient treatment options?

- 26.

In pregnant women with APS, with a history of at least one foetal death (>10WOG) or preterm birth (<34WOG) due to severe preeclampsia or placental insufficiency without previous history of thrombosis, what are the most efficient treatment options?

- 27.

In pregnant women with APS with previous history of thrombosis, regardless of her obstetric history, what are the most efficient treatment options?

- 28.

In pregnant women with APS, what is the influence of antiphospholipid antibodies in the clinical course and in the therapeutic decision?

- 29.

In women with APS, what are the most efficient treatment options during puerperium?

- 30.

In women with APS, which are the safest peripartum or peri-caesarean treatment options?

- 31.

In children of women with APS, which are the actions and procedures that should be implemented during the neonatal follow-up?

- 32.

In pregnant women with autoimmune disease, what is the risk of foetal exposure to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or analgesics (NSAIDs)?

- 33.

In pregnant women with autoimmune disease, what is the maternal and foetal risk of glucocorticoids exposure for disease treatment?

- 34.

In pregnant women with autoimmune disease, what is the foetal risk of exposure to antimalarial medication, azathioprine, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine A, leflunomide, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide and methotrexate?

- 35.

In pregnant women with autoimmune disease, what is the foetal risk of exposure to biological drugs (anti-TNF, rituximab and others)?

- 36.

In pregnant women with autoimmune disease during the breastfeeding period, what are the antirheumatic drugs that can be most safely employed?

- 37.

In pregnant women with autoimmune disease, what is the risk of foetal exposure to oral anticoagulants and heparin?

SLE is a multisystemic autoimmune disease of unknown cause, characterized by the production of diverse antibodies that affects mainly women in reproductive stage with normally conserved fertility.5

Maternal Morbidity1. In Women With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, What Are the Safest Contraceptive Options?The use of triphase oral contraceptives (ethinyl estradiol plus norethindrone) is not associated to the reactivation risk (assessed by SELENA-SLEDAI) of SLE and it does not increase the risk of known adverse events associated to its intake in healthy women6 [LOE Ib]. The use of combined oral contraceptives, progestogens alone and non-hormonal intrauterine devices does not increase the risk of aggravating the disease activity (assessed by SLEDAI) in patients with mild to moderate SLE; this has only been assessed in women without previous episodes of thrombosis7 [LOE Ib]. Contraception with cyproterone acetate (50mg) and clormadinone (5mg) is well tolerated and effective as contraceptive method in patients with mild, moderate or severe SLE8 [LOE III]. Triphase oral contraceptives and non-combined progestogens can be used in patients with SLE, as their use does not increase the disease activity or the risk of adverse events, especially episodes of thrombosis6,7 [GR A]. The use of triphase oral contraceptives and non-combined progestogens is not recommended in patients with previous history of thrombosis and/or pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors, neither is it recommended in patients with SLE with associated antiphospholipid antibodies and/or APS6,7 [GR A].

Contraception with progestogens (through different routes of administration) is safe and effective for all kind of patients with SLE at different activity degrees, and it can be administered in patients with positive antiphospholipid antibodies8,9 [GR C]. The intrauterine device with progestogens is safe and effective when a long-term (at least 5 years) contraceptive method is desired in women with SLE9 [GR C]. Emergency contraception based on progestogens is safe in women with SLE9 [GR C]. Combined barrier contraceptive methods (condoms and spermicide) can be used in patients with SLE; however, their low efficiency as contraceptive method must be considered.9 The definitive (surgical) contraceptive method is safe and effective; in patients with SLE, its use is recommended in those subjects with satisfied parity9 [GR C].

- •

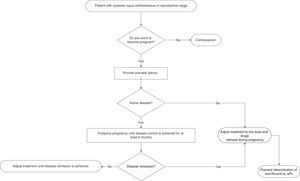

Physicians who provide health care to women with SLE must provide advice on contraception in a personalized way to all fertile women (Fig. 1) [GPP].

Pregnancy in patients with SLE, compared to the general population, is a high-risk pregnancy due to an elevated complication rate and maternal mortality rate10,11 [LOE III/IV]. The frequency of maternal and foetal complications during pregnancy of women with SLE is higher in unplanned pregnancies12 [LOE III]. Ideally, pregnancy in patients with SLE must be a planned event and there must be close preconception medical surveillance customized for each patient12,13 [GR C/D].

The primary objective of preconception control in patients with SLE that want to be pregnant is to make the patients achieve disease remission at least 6 months before allowing pregnancy13 [LOE IV]. Pregnancy is not recommended in patients with SLE who have received teratogenic drugs during the last 6 months (depending on each drug and assessing the risk-benefit ratio of its use) [GR D]. It is suggested for women with SLE that plan to become pregnant to have antiphospholipid, anti-DNAdc and anti-SSA/Ro and anti-SSB/La antibodies determinations done as part of the preconception assessment14 [GR D]. Pregnancy in women with SLE must be planned, monitored and considered high-risk in all cases11,13 [GR D]. Pregnancy in patients with SLE is contraindicated in women with severe pulmonary hypertension, restrictive pulmonary disease, heart failure, chronic renal failure (creatinine >2.8mg/dl), history of severe preeclampsia or HELLP syndrome (microangiopaty characterized by haemolytic anaemia, elevation of hepatic enzymes and thrombocytopenia), brain vascular event within the previous 6 months and severe SLE relapse during the last 6 months [GR D]. All fertile patients with SLE must receive medical advice (including the patient and her family) from the rheumatologist and the OB/GYN during the preconception period.

- •

If the patient is pregnant and active when she arrives to the physician's office, the reactivation must be immediately treated and she must be informed about the high risk of developing maternal and foetal complications [GPP].

In a prospective study on pregnant women with SLE compared to a control group (non-pregnant women), disease exacerbation was reported in 65% of the pregnant women vs 42% of the control group (P=.015)15 [LOE IIa]. At least 3 prospective studies show that pregnant women with SLE have a higher rate of disease relapse (between 58 and 65%) compared to non-pregnant women with SLE15–17 [LOE IIa]. At least 4 prospective studies on women with SLE showed a disease relapse rate of 27%–70% and it was not higher when compared to non-pregnant women with SLE18–21 [LOE IIa/IIb]. A SLE activity rate of 1.2 people/year in pregnant women vs 0.4 people/year in non-pregnant women (P<.0001) has been reported22 [LOE IIb]. A prospective study reported as risk factors of SLE activity during pregnancy: an elevated number of disease relapses before pregnancy (P<.05), the discontinuation of chloroquine during pregnancy (P<.05) and a high SLEDAI rate (>5) before pregnancy.22 In a retrospective study, it was observed that disease reactivation in patients with SLE is more frequent during pregnancy (36.5%±3.3%)23 [LOE III]. In women with SLE, pregnancy increases the risk of thrombotic events (brain vascular disease, brain thromboembolism and deep venous thrombosis), severe infections and thrombocytopenia10 [LOE III]. Pregnancy in patients with pre-existing lupus nephropathy increases the activity of renal disease (assessed by SELENA 2K); 47.5 vs 13.4% (P=.0001)24 [LOE III]. Pregnant patients with previous lupus nephritis have a greater risk of renal activity in any organ, compared to those patients that never had a renal condition (54.2 vs 25%; P=.004 and 45.7 vs 6.6%; P=.00001)25 [LOE III]. The following are risk factors of disease relapse in pregnant patients with SLE: active disease within 6 months before conception, multiple exacerbations before conception, treatment interruption during pregnancy and comorbidities26 [LOE IV]. The most frequent clinical manifestations of activity during pregnancy are: mucocutaneous (25%–90%), haematological (10%–40%), articular (20%) and renal (4%–30%)15,16,26 [LOE IIa]. Close medical surveillance and communication among a multidisciplinary team is recommended, as there is a high risk of disease relapse during pregnancy and immediate puerperium, especially in patients with previous lupus nephritis [GR C/D].

- •

Pregnant women with SLE should not abandon treatment [GPP].

As reported in a meta-analysis, the frequency of preeclampsia in patients with SLE is 7.6%, and 0.8% in the case of eclampsia. Moreover, the presence of active renal condition during pregnancy is a risk factor for the development of preeclampsia but not of eclampsia27 [LOE Ia]. A multicentre study from the USA reported a frequency of 22.5% of preeclampsia and 0.5% of eclampsia in pregnant patients with SLE (OR: 3 and 4.4 respectively, 95% CI, P<.001)10 [LOE III]. A prevalence study of HELLP syndrome in an open population and in patients with SLE reported a frequency of severe preeclampsia in pregnant patients with SLE of 10%–20% and of HELLP syndrome of 0.5%–0.9%28 [LOE III]. A retrospective study that included pregnant women with SLE (with and without previous renal condition) reported a preeclampsia frequency of 22.8% in patients with previous renal activity vs 13.3% in patients without it (P=0.2)25 [LOE III]. Risk factors for the development of preeclampsia/eclampsia described in pregnant patients with SLE are history of histologic class (WHO) iii and iv lupus nephritis, history of preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome, pre-existing high blood pressure, presence of antiphospholipid antibodies and active SLE29 [LOE IV]. Preeclampsia generally occurs as from 20 weeks of gestation, with increased levels of uric acid, normal C3 and C4, and normal double-chain anti-DNA antibodies. In active lupus nephropathy there is hypocomplementemia, elevated anti-DNAdc, normal or increased levels of uric acid and active urinary sediment, and it occurs at any time during gestation13,20 [LOE IV]. A differential diagnosis between lupus nephropathy and preeclampsia shall be performed in pregnant patients with SLE [GR D]. It should be considered that pregnant patients with SLE have a high risk of preeclampsia development; thus, minimum blood pressure elevations and fluctuations ranging from normal or low blood pressure to mild elevations can be symptoms of the beginning of preeclampsia. Young women or women over 35 years old, primigravida and with history of lupus and/or active nephropathy at the beginning of pregnancy are patients with the highest risk.30

Two meta-analysis showed that early administration (≤16 WOG) of low daily doses of aspirin (50–150mg) reduces the risk of developing severe preeclampsia (RR: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.08–0.57) or preeclampsia (RR: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.36–0.62) in women at risk of developing it31,32 [LOE Ia]. If there is no contraindication, the use of low doses of aspirin is recommended for all pregnant women with SLE to reduce the risk of preeclampsia development31,32 [GR A].

5. In Pregnant Women With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, What Are the Most Efficient Treatment Options to Prevent and Treat Disease Reactivation?A prospective placebo-controlled study that included pregnant patients with SLE showed that hydroxychloroquine reduces the risk of exacerbations but does not have an influence on foetal outcome33 [LOE Ib]. Hydroxychloroquine discontinuation during pregnancy increases the risk of SLE activity, including severe exacerbations such as severe urine protein and thrombocytopenia34 [LOE IIa]. The use of hydroxychloroquine is recommended to prevent SLE relapses during pregnancy33 [GR A].

A prospective study in pregnant patients with SLE concluded that the use of low doses of prednisone does not prevent disease relapses15 [LOE IIb]. The use of prednisone at doses higher than 20mg/d in pregnant patients with SLE increases the risk of preeclampsia and gestational diabetes35 [LOE IV]. The use of non-fluorinated glucocorticoids in pregnant patients with SLE is recommended to treat moderate to severe activity26 [GR D].

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., naproxene, ibuprofen and indomethacin) can be used during pregnancy for the control of joint manifestations; its use shall be avoided only in the third trimester to prevent foetal complications, especially the early closure of ductus arteriosus13 [GR D]. Azathioprine can be used during pregnancy in patients with SLE, in case of moderate to severe activity before pregnancy (continue the administration if it was administered before pregnancy or start administration during pregnancy, as necessary)35 [GR D]. Treatment with azathioprine should be continued in pregnant patients with SLE that received it before pregnancy, and patients taking mycophenolate mofetil or other immunosuppressant who want to become pregnant should switch to azathioprine administration (before pregnancy)35 [GR D]. The use of methotrexate and leflunomide is completely contraindicated during pregnancy26 [GR D]. In a number of cases of pregnant patients with SLE exposed to cyclophosphamide during the first or second gestation trimester, foetal loss was reported in 100% of the cases36 [LOE IV]. The use of mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide in pregnant patients with SLE shall be reserved only for severe activity cases that threaten the mother's life. It is essential to report the potential teratogenic effects in the foetus or to consider the pregnancy therapeutic discontinuation26 [GR D]. The use of intravenous (iv) gammaglobulin during the pregnancy of patients with SLE is safe and effective and represents a treatment option for those patients with recurrent foetal losses37 [LOE III]. There are no studies that analyze the security of the use of biological medications in pregnant patients with SLE, and the scarce information available derives from case reports; thus, these medications shall not be used during pregnancy and must be discontinued in case of accidental exposure38 [GR C]. It is advisable for patients with SLE that become pregnant to continue the treatment administered before pregnancy, provided that it does not include completely contraindicated drugs during pregnancy.15 It is necessary to personalize the SLE activity treatment during pregnancy, considering the activity seriousness and the potential adverse events on the foetus35,38 [GR D].

- •

It should be noted that most SLE reactivation cases during pregnancy and the postpartum period are mild to moderate in intensity, so the use of metilprednisolone pulses should be avoided, except in high-risk life-threatening situations [GPP].

In women with lupus nephritis, a frequency of 16% of spontaneous abortions, 3.6% of deaths and 2.5% of neonatal deaths has been reported27 [LOE Ia]. In a prospective study in pregnant women with SLE, it was found that the frequency of spontaneous abortions was 14% and of foetal death was 12%22 [LOE IIb]. Hypocomplementemia (P<.05), high blood pressure at conception (P>.001) and antiphospholipid antibodies (P<.05) are foetal loss predictors in pregnant women with SLE22 [LOE IIb]. SLE activity within 6 months before conception has been associated to foetal loss in 42% of cases36 [LOE IIb]. The disease clinical activity associated to hypocomplementemia and elevated anti-DNAdc antibodies titles are associated to foetal loss in pregnant women with SLE31 [LOE IIb]. Pregnancy is not recommended in women with active lupus nephritis27 [GR A]. SLE activity during pregnancy must be eventually identified and treated to reduce the risk of adverse foetal outcome (foetal loss, prematurity and intrauterine growth restriction)39,40 [GR B/C]. Patients with SLE are recommended to have an adequate disease control at least as from 6 months before pregnancy planning36 [GR B].

Associated APS is a foetal loss (risk 3.1 times higher) and spontaneous abortion (risk 5 times higher) predictor. Thrombocytopenia during the first trimester is associated to foetal loss (risk 3.3 times higher)41 [LOE IIb]. High blood pressure during the first trimester of gestation is associated to foetal loss (risk 2.4 times higher) and death (risk 3.4 times higher)41 [LOE IIb]. Chronic systemic high blood pressure (before pregnancy or acquired in the first trimester) shall be controlled to reduce the risk of adverse foetal outcome (foetal loss, prematurity and intrauterine growth restriction)22,40–42 [GR B/C].

Hypocomplementemia and urine protein >1g/24h are foetal loss predictors in women with lupus nephritis43 [LOE IIb]. Lupus nephritis (OR: 7.3), anticardiolipine antibodies (OR: 3.9) and disease activity during pregnancy (OR: 1.9) are foetal loss predictors40 [LOE III]. In women with chronic renal disease, pregnancy can accelerate the renal function deterioration and worsen high blood pressure and urine protein, with a higher risk of maternal mortality and foetal complications (such as intrauterine growth delay)44 [LOE IV]. In women with lupus nephritis, pregnancy can be planned if renal function is normal or presents minimal damage (serum creatinine <1.5mg/dl, creatinine clearance ≥60ml/min, urine protein <1g/24h)43,45 [GR C].

7. In Pregnant Women With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, What Are the Frequency and Risk Factors Associated to Preterm Birth?The reported frequency of prematurity in foetus of pregnant women with lupus nephritis is 39.4% (95% CI: 32.4–46.4%)27 [LOE Ia]. The clinical activity of the disease along with the presence of hypocomplementemia and elevated high anti-DNAdc antibodies titles is associated to prematurity in foetus of women with SLE39 [LOE IIb]. The measurement of serum complement (C3 and C4) and anti-DNadc antibodies is recommended to identify pregnant women with SLE with foetal loss and prematurity risk39 [GR B].

High blood pressure during pregnancy and preeclampsia increase the risk of prematurity in foetus of pregnant women with SLE22,42 [LOE IIb]. Positive antiphospholipid antibodies (OR: 3.6; 95% CI: 1.5–8.7; P=.004) and active disease at conception (OR: 5.5; 95% CI: 2.3–12.8; P<.0001) increase the risk of prematurity in foetus of women with SLE46 [LOE III]. A retrospective analysis of 396 pregnancies determined that the presence of lupus nephritis (OR: 18.8; 95% CI: 1.5–125.9; P=.02), anti-Ro antibodies (OR: 13.9; 95% CI: 1.0–116.4; P=.04) and disease relapses (OR: 2.4; 95% CI: 1.3–4.5; P=.003) was associated to prematurity in pregnant women with SLE40 [LOE III]. High blood pressure and disease activity control is recommended to reduce prematurity risk in pregnant women with SLE22,40,42,46 [GR B/C].

8. In Foetus of Pregnant Women With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, What Are the Frequency and Risk Factors Associated to Low Birth Weight/intrauterine Growth Restriction/small for Gestational Age?The reported frequency of intrauterine growth restriction in foetus of pregnant women with lupus nephritis is 12.7% (95% CI: 32.4–46.4%)27 [LOE Ia]. The frequency of low birth weight is higher in foetus of women with lupus nephritis compared to women without the disease (46 vs 20%, P=.01)24 [LOE IIb]. In a prospective study of pregnant women with SLE, intrauterine growth restriction was observed in 35% of cases22 [LOE IIb]. Active disease at conception has been associated to intrauterine growth restriction (OR: 3.2; 95% CI: 1.3–7.6; P<.007)46 [LOE IIb]. A prospective study of 29 pregnancies in women with SLE showed that low serum albumin levels, antiphospholipid antibodies, gestational urine protein, high blood pressure and anti-Sm antibodies were associated to low birth weight47 [LOE IIb]. In women with SLE, urine protein has been associated to small foetus for their gestational age48 [LOE III]. A retrospective analysis of 396 pregnancies in women with SLE determined that the presence of anti-La antibodies (OR: 11.4; 95% CI: 1.1–115.1; P=.03), high blood pressure (OR: 37.7; 95% CI: 3.6–189.7; P=.02), Raynaud's phenomenon (OR: 12.2; 95% CI: 2.1–69.7; P=.005) and disease activity (OR: 4.1; 95% CI: 1.3–13.1; P=.01) were associated to intrauterine growth restriction40 [LOE III].

9. In Women With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, How Is the Follow-up During Pregnancy and Immediate Puerperium Carried out?Pregnancy in women with SLE must be considered a high-risk pregnancy10 [LOE III]. The frequency of complications during pregnancy of women with SLE, such as disease relapse, foetal loss, prematurity and neonatal asphyxiation, is greater when pregnancy is unplanned12 [LOE III]. During the pregnancy of a patient with SLE, the patient must be assessed by the rheumatologist every 4–6 weeks and by the OB/GYN every 4 weeks up to week 20 of gestation, every 2 weeks up to week 28 of gestation and weekly until delivery35,49–51 [GR D]. At the beginning of pregnancy, C3, C4, CH50, anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-Sm, anti-DNAdc antibodies and anticardiolipine, as well as lupus anticoagulant should be determined13,52 [GR D]. During the pregnancy of women with SLE, it is recommended to perform a monthly complete blood count, blood biochemistry, serum electrolytes, general urine test, creatinine/urine protein rate, C3, C4, CH50 and anti-DNAdc13,52 [GR D]. During the pregnancy of women with SLE, it is recommended to perform foetal ultrasounds between week 7 and 13 of gestation and monthly after week 16 of gestation to determine foetal anomalies and monitor the growth52 [GR D]. It is recommended to carry out foetal well-being tests weekly as of week 26 of gestation52 [GR D].

10. In Foetus of Women Containing Positive Anti-Ro and/or Anti-La Antibodies, What Are the Most Effective Prevention and Treatment Options for the Management of Congenital Heart Block?Cardiac neonatal lupus risk in children of mothers with anti-Ro antibodies is 2% and with anti-La antibodies is 5%53–55 [LOE IIb]. CHB recurrence rate associated to anti-Ro antibodies is 17%56 [LOE IIb]. Neonatal cardiac lupus mortality rate is around 20%53,57 [LOE III]. In pregnant women with positive anti-Ro and/or anti-La antibodies, a foetal echocardiography must be performed weekly from week 16 to week 26 of gestation14,52,58 [GR D].

A multicentre, open, with no randomized selection study did not show any benefits derived from the use of dexametasone to revert third degree CHB or the lack of progression from second to third degree CHB59 [LOE IIb]. A retrospective, multinational, multicentre study in 175 patients did not find significant differences in survival of foetus treated or not with fluorinated glucocorticoids, regardless of the dose, CHB degree and/or presence of anti-RO antibodies60 [LOE III]. The use of fluorinated glucocorticoids is not recommended in foetus with third degree CHB59,60 [GR C].

In a sub-analysis of 2 retrospective studies, with foetus belonging to positive anti-Ro/anti-La mothers, a CHB reversion from second degree to sinusal rhythm or first degree block was found in 35% of the cases exposed to dexametasone, compared to 6.25% of cases not exposed (P=.053)57,60 [LOE III]. The use of fluorinated glucocorticoids is recommended in foetus with second degree CHB57,60 [GR C].

In 2 prospective, multicentre studies in pregnant women of <12WOG, with positive anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies and at least one previous birth with CHB/neonatal lupus, the use of iv gammaglobulin (400mg/kg) every 3 weeks, from week 12 to 24 of gestation, did not prevent the recurrence of CHB61,62 [LOE IIb]. The use of gammaglobulin iv is not recommended for the prevention of CHB recurrence in pregnant women with anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies61,62 [GR B].

A retrospective study in 20 patients treated with iv gammaglobulin (1g/kg per 1–3 doses), combined with glucocorticoids, showed 80% of live births with established neonatal cardiac lupus (cardiomyopathy)63 [LOE III]. A report of 2 cases showed second to first degree CHB reversion with the combined use of dexamethasone 4mg/d, iv gammaglobulin (1g/kg every 15d) and weekly plasmapheresis until birth64 [LOE IV]. The use of therapy combined with glucocorticoids, iv gammaglobulin and plasmapheresis creates second and third line interventions to revert second degree CHB64 [GR D].

A case control study determined that exposure to hydroxychloroquine during pregnancy in women with SLE and positive anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies can reduce the risk of developing neonatal cardiac lupus (OR: 0.46; 95% CI: 0.18–1.18; P=.10)65 [LOE III]. A retrospective study of 3 cohorts determined that the use of hydroxychloroquine during pregnancy in women with SLE and positive anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies reduces the risk of developing recurrent neonatal cardiac lupus (OR: 0.23; 95% CI: 0.06–0.92; P=.037)66 [LOE III]. It is recommended to continue the use of hydroxychloroquine during pregnancy in women with positive anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies to reduce the risk of developing recurrent neonatal cardiac lupus65,66 [GR C].

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsAuthors state that no experiments were performed on human beings or animals as part of this investigation.

Data confidentialityAuthors state that this article does not contain patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentAuthors state that this article does not contain patient data.

Conflict of InterestThe Mexican College of Rheumatology received unrestricted educational support from the company UCB. The staff working at UCB had no interference with the information vested herein and did not participate in any meetings of the working group.

Please cite this article as: Saavedra Salinas MÁ, Barrera Cruz A, Cabral Castañeda AR, Jara Quezada LJ, Arce-Salinas CA, Álvarez Nemegyei J, et al. Guías de práctica clínica para la atención del embarazo en mujeres con enfermedades reumáticas autoinmunes del Colegio Mexicano de Reumatología. Parte I. Reumatol Clin. 2015;11:295–304.