(1) To analyse the implementation of multidisciplinary care models in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) patients, (2) To define minimum and excellent standards of care.

MethodsA survey was sent to clinicians who already performed multidisciplinary care or were in the process of undertaking it, asking: (1) Type of multidisciplinary care model implemented; (2) Degree, priority and feasibility of the implementation of quality standards in the structure, process and result for care. In 6 regional meetings the results of the survey were presented and discussed, and the ultimate priority of quality standards for care was defined. At a nominal meeting group, 11 experts (rheumatologists and dermatologists) analysed the results of the survey and the regional meetings. With this information, they defined which standards of care are currently considered as minimum and which are excellent.

ResultsThe simultaneous and parallel models of multidisciplinary care are those most widely implemented, but the implementation of quality standards is highly variable. In terms of structure it ranges from 22% to 74%, in those related to process from 17% to 54% and in the results from 2% to 28%. Of the 25 original quality standards for care, 9 were considered only minimum, 4 were excellent and 12 defined criteria for minimum level and others for excellence.

ConclusionsThe definition of minimum and excellent quality standards for care will help achieve the goal of multidisciplinary care for patients with PAs, which is the best healthcare possible.

1) Analizar la implementación de los modelos de atención multidisciplinar en pacientes con artritis psoriásica (APs), y 2) definir estándares de calidad de mínimos y de excelencia.

MétodosSe envió una encuesta a profesionales que ya realizan atención multidisciplinar o están en vías preguntando por: 1) tipo de modelo de abordaje multidisciplinar, y 2) grado, prioridad y facilidad de la implementación de los estándares de calidad de estructura, proceso y resultado. En 6 reuniones regionales se presentaron y discutieron los resultados de la encuesta, tanto a nivel nacional como regional, y se definió la prioridad definitiva de los estándares de calidad. En una reunión de grupo nominal, 11 expertos (reumatólogos y dermatólogos) analizaron los resultados de la encuesta y las reuniones regionales. Con ello definieron qué estándares de calidad son actualmente de mínimos y cuáles de excelencia.

ResultadosLos modelos de atención multidisciplinar conjunto y paralelo son los más implementados, y los de los estándares de calidad es muy variable: en los de estructura varía del 22 al 74%, en los de proceso del 17 al 54% y en los de resultado del 2 al 28%. De los 25 estándares de calidad originales, 9 se consideran solo de mínimos, 4 de excelencia y 12 tienen definidos unos criterios para ser de mínimos y otros para la excelencia.

ConclusionesLa definición de estándares de calidad de mínimos y de excelencia ayudará en la consecución del objetivo de la atención multidisciplinar para pacientes con APs, que es la mejor asistencia sanitaria posible.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic and progressive disease that greatly impacts patients’ quality of life.1–4 In routine clinical practice, many patients are assessed by dermatologists and rheumatologists independently, which results in the care process possibly being less than optimal from a from a clinical and patient point of view, and even in terms of the efficiency of the system.5–7 Therefore, various units have been set up in Spain for the multidisciplinary care of patients with PsA where rheumatologists and dermatologists work closely together.8 This multidisciplinary approach is also recommended by major organisations such as the European League Against Rheumatism.9

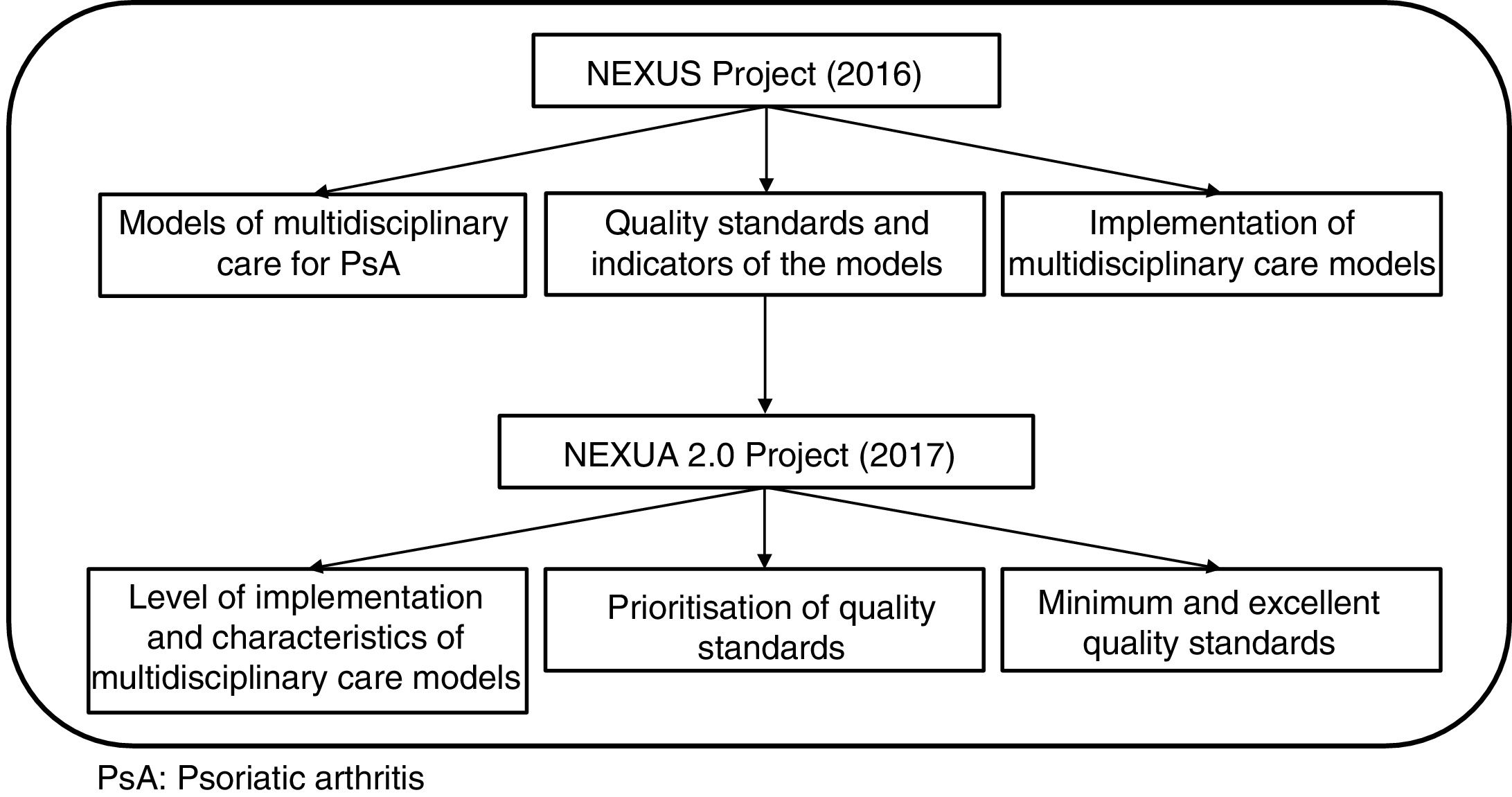

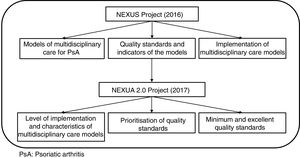

With the above in mind, the NEXUS project was implemented in 2016 to promote and standardise the multidisciplinary care of patients with PsA to ensure care of maximum quality for these patients.

To that end the various multidisciplinary care models implemented in our country were studied, and quality standards were created (structure, process, outcome), as well as quality indicators.10 These quality models and variables were also positively evaluated by patients and hospital managers. All this information was later disseminated regionally to provide a point of departure for rheumatologists and dermatologists interested in starting a multidisciplinary care model of any type.

The NEXUS 2.0 project was launched in 2017 to analyse the situation of multidisciplinary care models already implemented or in the process of implementation, such as the quality standards defined in the previous project. Although NEXUS recommends that standards should be assessed after 2 years, bearing in mind all of the above, and particularly all the barriers and limitations described in the NEXUS project for implementing models in hospitals that already have them, analysis of the first months’ dissemination of these models to centres interested in implementing them might be helpful when evaluating areas for improvement, and in generating new proposals to promote the most effective implementation possible.

This might serve not only as a guideline for professionals who want to start multidisciplinary care for patients with PsA, but also as the basis to continue to evolve, and improve this multidisciplinary care.

MethodsNEXUS 2.0 study designContinuation study of the NEXUS project, described below. The objectives of this new phase were: (1) to study the implementation of the various multidisciplinary care models for patients with PsA, and their quality standards, all of which had been developed during the previous phase, NEXUS project, and (2) to define minimum quality standards to encourage and foster the implantation of these models. A mixed methodology was followed to achieve this, and it was undertaken in 3 phases. The first was a quantitative phase that involved the completion and analysis of a survey, and the second a qualitative study, which in turn comprised regional meetings, followed by a national meeting.

NEXUS projectA study designed to foster and promote multidisciplinary care for PsA. The study analysed Spain's current multidisciplinary care models, and a series of quality standards and indicators were generated for the appropriate care of these patients. Part of this study – the analysis of the multidisciplinary care models for PsA – has been described previously.10 In sum, this project was undertaken during 2016, after a literature review of the various multidisciplinary care models for PsA, and another systematic review to find quality standards and indicators created for these patients. All the information obtained was presented and discussed in a nominal group meeting with the 24 experts on the project, 12 rheumatologists, who provide multidisciplinary care for patients with PsA in their daily practice. The various multidisciplinary care models in Spain were analysed in this meeting. Twelve different multidisciplinary care models were described, implemented for at least 1–2 years, that were globally grouped into 3 different subtypes: joint face-to-face, parallel face-to-face, and preferential circuit. Moreover, a series of preliminary, quality standards of structure, process and outcome was also defined for these multidisciplinary care models, and their corresponding quality indicators. After this meeting, by means of structured and individual interviews with the 24 experts, data were collected that included the centre, department and population attended, on the multidisciplinary care model (type, material and human resources, requirements of professionals, objectives, entry and exit criteria, agendas, action protocols, responsibilities, decision making, research and teaching activities, joint clinical sessions, creation/starting, planning, advantages/disadvantages of the model and barriers/facilitators in implementing the model). Following the meeting, the preliminary quality standards and indicators were also voted on with a Delphi round where, in addition to the level of agreement, their priority and feasibility of implementation were also evaluated.

Furthermore, after all the above, 2 focus groups were held, one with patients with PsA, and the other with hospital managers, that assessed the models and the provisional standards and indicators, and comments were generated that were also considered by the experts. A definitive total of 25 quality standards, and 24 quality indicators was obtained. This final phase is awaiting publication.

Finally, all this information was disseminated in regional meetings with, in addition to the 24 NEXUS experts, rheumatologists and dermatologists interested in implementing this type of multidisciplinary care in their hospitals (Fig. 1).

NEXUS 2.0 surveyA structured on-line survey was sent to the NEXUS project participants (both those already using multidisciplinary care, and those interested in implementing it) where they were asked about: (1) type of multidisciplinary approach model (joint, parallel, preferential circuit, other, awaiting creation); (2) level of implementation of the quality standards of structure, process and outcome, (yes/no); (3) priority in implementing quality standards (from 1 to 5, 1=low priority, 5=high priority), and (4) ease of implementing quality standards of structure, process and outcome (from 1 to 5, 1=very easy, 5=very difficult).

NEXUS 2.0 regional meetingsA total of 6 regional meetings were held in which the national and regional results of the survey were presented. These were discussed along with the barriers and facilitators in implementing the models, and the quality standards of structure, process and outcome. Following this, the priority of the quality standards was reassessed, and their definitive priority defined.

NEXUS 2.0 national meetingIn a nominal group meeting, 11 experts in multidisciplinary care (rheumatologists and dermatologists) analysed the results of the survey and regional meetings. From that they defined both the current minimum and excellent quality standards. Minimum quality standards were those that should always be met, regardless of the type of multidisciplinary care model. On the other hand, excellent standards would not be mandatory but would add extra quality for the areas meeting them, and of course it should be the objective of all models to implement these standards.

Statistical analysisDescriptive data analysis was performed.

ResultsImplementation of multidisciplinary care models for psoriatic arthritis and quality standards of structure process and outcomeFifty centres were included, of which 79% had already implemented a multidisciplinary care model for patients with PsA. The joint approach at 38% was the most implemented, followed by the parallel approach (27%), and the preferential circuit (27%). Eight percent reported that they were implementing a model that currently resembles the preferential circuit but that would be changed towards a joint or parallel model.

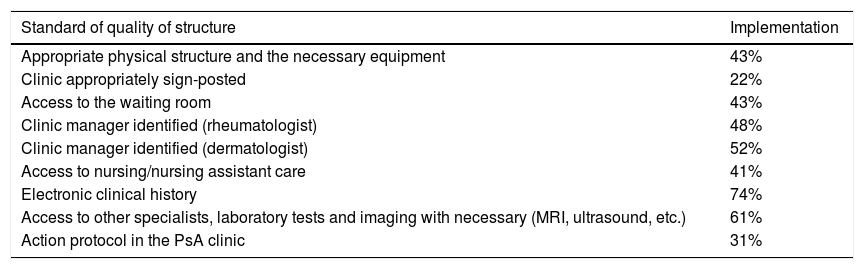

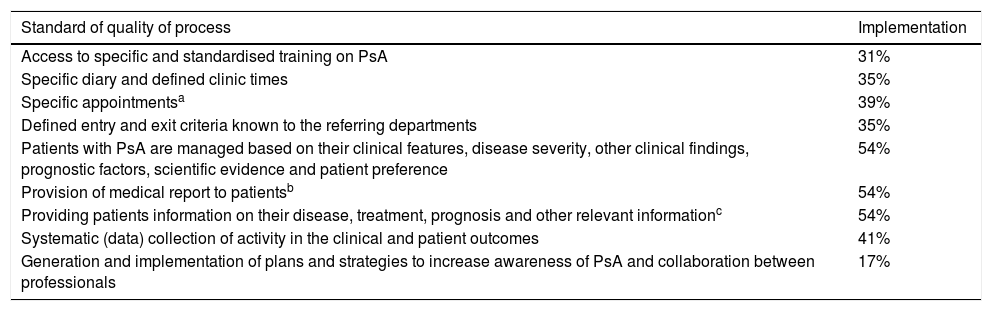

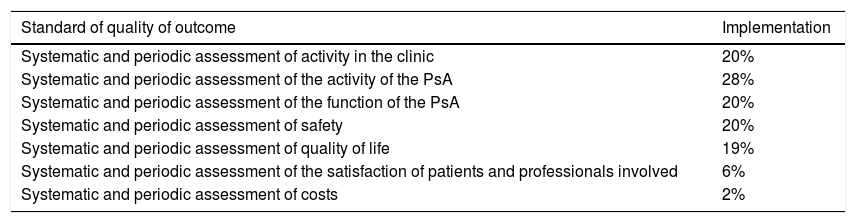

The degree of implementation of the quality standards defined earlier in the NEXUS project (Tables 1–3) was very variable. Among the quality standards of structure (Table 1), an electronic clinical history was available in more than 70% of the centres, but correct signposting of the clinic only in 22%. Of the quality standards of process (Table 2), providing the patient with a medical report had only been implemented in 54% of the centres, but plans and strategies for increasing awareness of PsA and collaboration between professionals had only been generated and implemented in 17%. However, the very low level of implementation of quality standards of outcome is striking (Table 3). Twenty-eight percent undertook systematic, periodic evaluations of the activity of PsA, in contrast, only 2% undertook systemic and periodic evaluations of costs.

Degree of implementation of standards of quality of structure for multidisciplinary care models for patients with PsA.

| Standard of quality of structure | Implementation |

|---|---|

| Appropriate physical structure and the necessary equipment | 43% |

| Clinic appropriately sign-posted | 22% |

| Access to the waiting room | 43% |

| Clinic manager identified (rheumatologist) | 48% |

| Clinic manager identified (dermatologist) | 52% |

| Access to nursing/nursing assistant care | 41% |

| Electronic clinical history | 74% |

| Access to other specialists, laboratory tests and imaging with necessary (MRI, ultrasound, etc.) | 61% |

| Action protocol in the PsA clinic | 31% |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Degree of implementation of the standards of quality of process for multidisciplinary care models for patients with PsA.

| Standard of quality of process | Implementation |

|---|---|

| Access to specific and standardised training on PsA | 31% |

| Specific diary and defined clinic times | 35% |

| Specific appointmentsa | 39% |

| Defined entry and exit criteria known to the referring departments | 35% |

| Patients with PsA are managed based on their clinical features, disease severity, other clinical findings, prognostic factors, scientific evidence and patient preference | 54% |

| Provision of medical report to patientsb | 54% |

| Providing patients information on their disease, treatment, prognosis and other relevant informationc | 54% |

| Systematic (data) collection of activity in the clinical and patient outcomes | 41% |

| Generation and implementation of plans and strategies to increase awareness of PsA and collaboration between professionals | 17% |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis.

“Specific appointments” refers to issuing a paper or similar showing all the data referring to date, time and other information about a medical appointment. “Specific diary” refers to an administrative issue and acknowledging a specific medical space for this activity.

Degree of implementation of the standards of quality of outcome for the multidisciplinary care models for patients with PsA.

| Standard of quality of outcome | Implementation |

|---|---|

| Systematic and periodic assessment of activity in the clinic | 20% |

| Systematic and periodic assessment of the activity of the PsA | 28% |

| Systematic and periodic assessment of the function of the PsA | 20% |

| Systematic and periodic assessment of safety | 20% |

| Systematic and periodic assessment of quality of life | 19% |

| Systematic and periodic assessment of the satisfaction of patients and professionals involved | 6% |

| Systematic and periodic assessment of costs | 2% |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis.

Priority of implementation (material in the annexe) varied according to the standard but was high in general, especially for some. Of the standards of structure, the availability of an adequate physical structure, the necessary equipment, and action protocols in PsA clinics, and of the standards of process, managing patients with PsA based on their clinical features, severity, etc., and their preferences, and informing patients about their disease, treatments, prognosis, and other relevant information were considered the highest priority. Lastly, of the standards of outcome, the highest priority quality standards were systemic and periodic assessment of disease activity, and patient safety.

Finally, in terms of ease of implementation (material in the annexe), except for the quality standards of outcome, most of the quality standards of structure and process were considered very easy to implement.

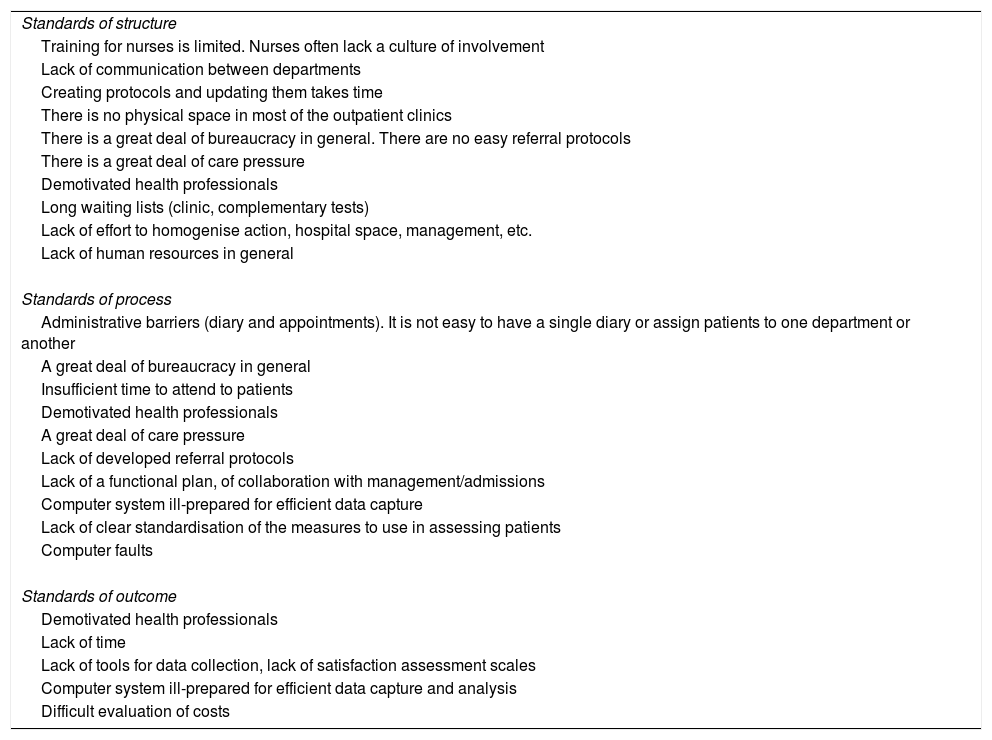

On the other hand, barriers and other difficulties in implementing quality standards were gathered. These are described in Table 4, highlighting the lack of time and involvement of all the actors, particularly from management and admissions.

Barriers to the implementation of standards of quality of structure, process and outcomes.

| Standards of structure |

| Training for nurses is limited. Nurses often lack a culture of involvement |

| Lack of communication between departments |

| Creating protocols and updating them takes time |

| There is no physical space in most of the outpatient clinics |

| There is a great deal of bureaucracy in general. There are no easy referral protocols |

| There is a great deal of care pressure |

| Demotivated health professionals |

| Long waiting lists (clinic, complementary tests) |

| Lack of effort to homogenise action, hospital space, management, etc. |

| Lack of human resources in general |

| Standards of process |

| Administrative barriers (diary and appointments). It is not easy to have a single diary or assign patients to one department or another |

| A great deal of bureaucracy in general |

| Insufficient time to attend to patients |

| Demotivated health professionals |

| A great deal of care pressure |

| Lack of developed referral protocols |

| Lack of a functional plan, of collaboration with management/admissions |

| Computer system ill-prepared for efficient data capture |

| Lack of clear standardisation of the measures to use in assessing patients |

| Computer faults |

| Standards of outcome |

| Demotivated health professionals |

| Lack of time |

| Lack of tools for data collection, lack of satisfaction assessment scales |

| Computer system ill-prepared for efficient data capture and analysis |

| Difficult evaluation of costs |

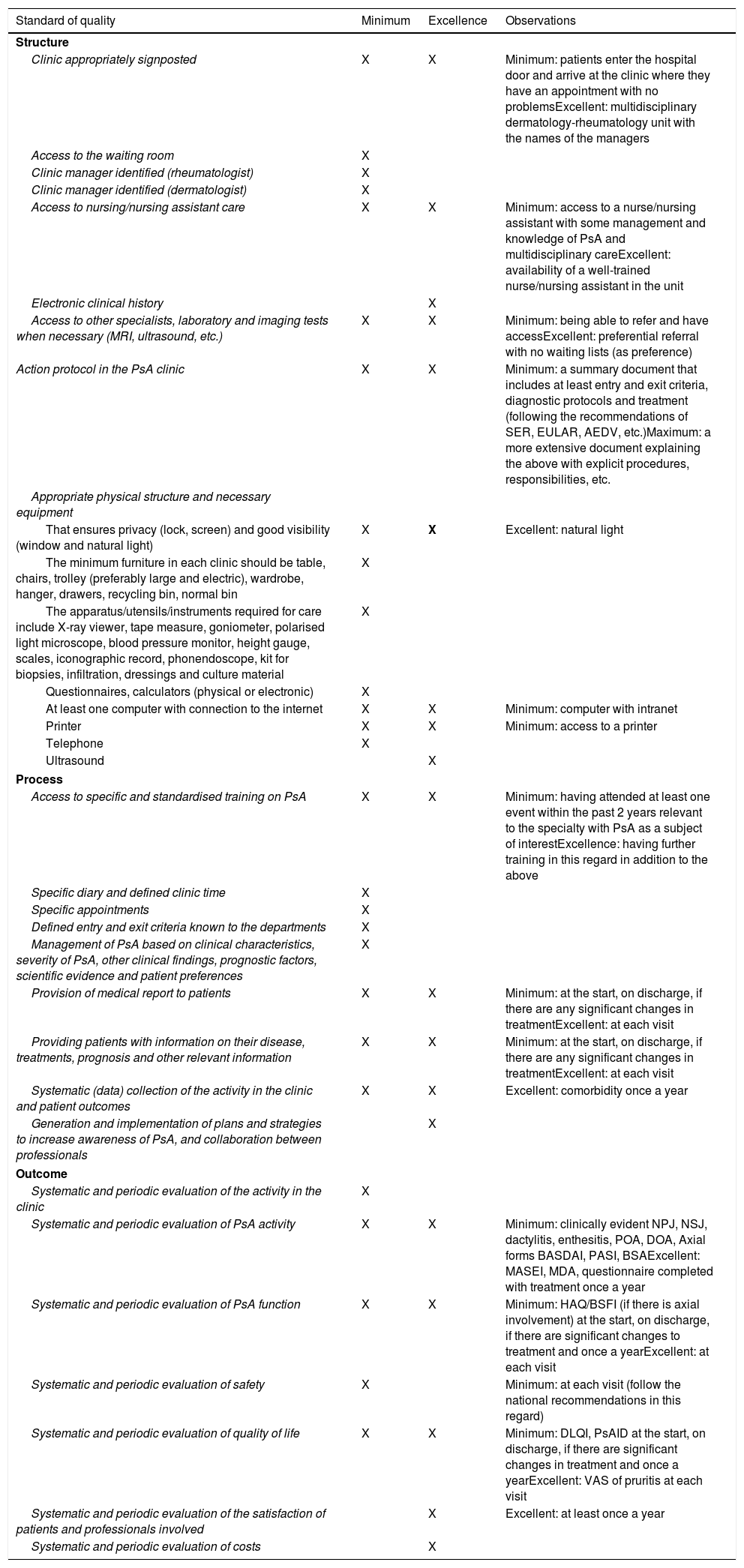

Table 5 shows the minimum and excellent quality standards once all the above had been discussed by the experts. Some were considered minimum, such as access to the waiting room, and for clinic managers to be clearly identified. Others were considered excellent, such as the availability of an ultrasound machine in the multidisciplinary care clinic. Some of the levels that would be considered minimum and excellent quality were sub-specified. For example, for the standard of quality on access to nursing/nursing assistant care, access to a nurse or nursing assistant with some knowledge and management of PsA and multidisciplinary care was considered a minimum quality standard, whereas an excellent quality standard would be to have a well-trained nurse/nursing assistant as part of the multidisciplinary care unit.

Minimum and excellent standards of quality of structure, process and outcome.

| Standard of quality | Minimum | Excellence | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | |||

| Clinic appropriately signposted | X | X | Minimum: patients enter the hospital door and arrive at the clinic where they have an appointment with no problemsExcellent: multidisciplinary dermatology-rheumatology unit with the names of the managers |

| Access to the waiting room | X | ||

| Clinic manager identified (rheumatologist) | X | ||

| Clinic manager identified (dermatologist) | X | ||

| Access to nursing/nursing assistant care | X | X | Minimum: access to a nurse/nursing assistant with some management and knowledge of PsA and multidisciplinary careExcellent: availability of a well-trained nurse/nursing assistant in the unit |

| Electronic clinical history | X | ||

| Access to other specialists, laboratory and imaging tests when necessary (MRI, ultrasound, etc.) | X | X | Minimum: being able to refer and have accessExcellent: preferential referral with no waiting lists (as preference) |

| Action protocol in the PsA clinic | X | X | Minimum: a summary document that includes at least entry and exit criteria, diagnostic protocols and treatment (following the recommendations of SER, EULAR, AEDV, etc.)Maximum: a more extensive document explaining the above with explicit procedures, responsibilities, etc. |

| Appropriate physical structure and necessary equipment | |||

| That ensures privacy (lock, screen) and good visibility (window and natural light) | X | X | Excellent: natural light |

| The minimum furniture in each clinic should be table, chairs, trolley (preferably large and electric), wardrobe, hanger, drawers, recycling bin, normal bin | X | ||

| The apparatus/utensils/instruments required for care include X-ray viewer, tape measure, goniometer, polarised light microscope, blood pressure monitor, height gauge, scales, iconographic record, phonendoscope, kit for biopsies, infiltration, dressings and culture material | X | ||

| Questionnaires, calculators (physical or electronic) | X | ||

| At least one computer with connection to the internet | X | X | Minimum: computer with intranet |

| Printer | X | X | Minimum: access to a printer |

| Telephone | X | ||

| Ultrasound | X | ||

| Process | |||

| Access to specific and standardised training on PsA | X | X | Minimum: having attended at least one event within the past 2 years relevant to the specialty with PsA as a subject of interestExcellence: having further training in this regard in addition to the above |

| Specific diary and defined clinic time | X | ||

| Specific appointments | X | ||

| Defined entry and exit criteria known to the departments | X | ||

| Management of PsA based on clinical characteristics, severity of PsA, other clinical findings, prognostic factors, scientific evidence and patient preferences | X | ||

| Provision of medical report to patients | X | X | Minimum: at the start, on discharge, if there are any significant changes in treatmentExcellent: at each visit |

| Providing patients with information on their disease, treatments, prognosis and other relevant information | X | X | Minimum: at the start, on discharge, if there are any significant changes in treatmentExcellent: at each visit |

| Systematic (data) collection of the activity in the clinic and patient outcomes | X | X | Excellent: comorbidity once a year |

| Generation and implementation of plans and strategies to increase awareness of PsA, and collaboration between professionals | X | ||

| Outcome | |||

| Systematic and periodic evaluation of the activity in the clinic | X | ||

| Systematic and periodic evaluation of PsA activity | X | X | Minimum: clinically evident NPJ, NSJ, dactylitis, enthesitis, POA, DOA, Axial forms BASDAI, PASI, BSAExcellent: MASEI, MDA, questionnaire completed with treatment once a year |

| Systematic and periodic evaluation of PsA function | X | X | Minimum: HAQ/BSFI (if there is axial involvement) at the start, on discharge, if there are significant changes to treatment and once a yearExcellent: at each visit |

| Systematic and periodic evaluation of safety | X | Minimum: at each visit (follow the national recommendations in this regard) | |

| Systematic and periodic evaluation of quality of life | X | X | Minimum: DLQI, PsAID at the start, on discharge, if there are significant changes in treatment and once a yearExcellent: VAS of pruritis at each visit |

| Systematic and periodic evaluation of the satisfaction of patients and professionals involved | X | Excellent: at least once a year | |

| Systematic and periodic evaluation of costs | X | ||

AEDV: Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BSA: Body Surface Area; DLQI: Dermatology Quality of Life Index; EULAR: European League Against Rheumatism; VAS: visual analogue scale; HAQ: Health assessment Questionnaire; MASEI: Madrid Sonographic Enthesitis Index; MDA: Minimal Disease Activity; NPJ: number of painful joints; NSJ: number of swollen joints; PASI: Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PsAID: Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; SER: Spanish Society of Rheumatology; DOA: doctor's overall assessment; POA: patient's overall assessment.

Continuing with standards of outcome, again some are considered only minimum, such as the provision of a specific diary and set consultation times or entrance and exit times defined and known by the departments. Others were considered excellent such as the generation and implementation of plans and strategies to increase awareness of Pas, and collaboration between professionals. And finally, several had indications as minimum standards and others as excellent standards. Such as the quality standards on providing patients with a medical report or the standard referring to the information that they should be given; a minimum quality standard would be to do so at the start, on discharge, or if there are significant changes in treatment, and doing so at each visit would be an excellent quality standard.

Finally, regarding the quality standards of outcome, we found minimum quality standards such as the systematic and periodic evaluation of safety; excellent quality standards, such as the systematic and periodic evaluation of costs, and some where it was specified why they would be minimum or excellent.

DiscussionIn this document we present the results of the NEXUS 2.0 PROJECT. The ultimate objective of the NEXUS project was to improve the care, quality of life and satisfaction of patients with PsA, and achieve improved use of health resources.10 To that end the various models implemented in our country were analysed and characterised in depth, and were basically grouped into 3 different formats, joint care, parallel care model, and preferential circuit models.10 But once these multidisciplinary care models have been established, it is essential to evaluate their activity to demonstrate their efficacy and assess areas for improvement, as has been done in other areas of rheumatology.11–16 Hence a series of quality standards and indicators has been defined based on best evidence and experience that were evaluated and endorsed by patients and healthcare managers.

In this continuation of the initial project we have confirmed, on the one hand, the great interest in developing multidisciplinary care for PsA among rheumatologists and dermatologists, reflected in the implementation of a multidisciplinary care model of some type in several centres. As we expected, the model implemented varies according to the characteristics and circumstances of each centre; the joint and parallel models being the most implemented.

The implementation of quality standards varies greatly. Firstly, we would highlight the low level of implementation of standards of quality of outcome. As we observed in the local meetings, one of the principal barriers in implementing these standards, in addition to lack of time, is the lack of an efficient electronic data collection system to continue with these processes and routine clinical activity in clinics, which, at the same time, enables data collection in a format (coding) that enables subsequent exploitation and statistical analysis. Any change to this situation requires the involvement of various actors including managers, computer consultants and clinicians, and this is not without its difficulties.

Although standards of structure are the most implemented subgroup of standards, it is striking that two thirds of the centres do not currently have an action protocol in their PsA clinics. Although many clinical processes are internalised, implementing agreed protocols in this area could be of enormous help in reducing variability of clinical practice. Furthermore, if all issues relating to activity in different models (level of responsibility, actions to be taken if a manager cannot attend the clinic, how prescriptions of biological therapies are assigned, etc.) are covered in writing, this will prevent confusion and other problems.

We also want to highlight the low level of implementation of standards of process for the systematic assessment of patients with PsA, which has already been confirmed in other studies.17 Again, the great care pressure with the consequent limitation of time in the clinic, and the lack of an efficient data collection system and the variability of the type of variables to use in assessing PsA might have contributed decisively to this. In this regard, a group of experts have recently standardised the clinical assessment of patients with axial spondyloarthritis and PsA by creating a checklist (ONLY TOOLS project),18 in which, in addition to making the assessment of these patients systematic based on best evidence and experience, various formats have been generated of this checklist to facilitate data collection.

As we have shown, this second phase of the NEXUS project has made clear that the feasibility of implementing quality standards is not uniform, and there are a series of difficulties and other barriers that are not helpful. Therefore, bearing in mind the final objective of multidisciplinary care – clinical excellence – the project's group of experts defined which quality standards would be minimum, i.e., essential, and which would indicate excellent care. However, they also defined minimum and excellent levels within some of the quality standards. We consider that this classification of standards adapts more realistically to the characteristics of multidisciplinary care currently practiced in our country and will serve to motivate and help centres that have more difficulties in implementing these models and standards. Finally, in this regard we would like to highlight that both the rheumatologists and dermatologists were in full alignment both in the situation analysis and in relation to developing these minimum standards.

We would like to highlight that this project has some limitations. Firstly, both the rheumatologists and dermatologists who took part are particularly interested in multidisciplinary care, which might mean that these data do not properly reflect the current situation in multidisciplinary care. However, considering the high number of participants, we believe to an extent that this might be a good reflection of what is happening in our country. Furthermore, and given that a large part of this study was based on meetings and the opinion of the participants (including a self-reported questionnaire), it also might not be a good reflection of the real situation in multidisciplinary care (unlike an epidemiological study). However, the same arguments, barriers and facilitators were repeated, as well as the agreement in this regard between rheumatologists and dermatologists, which adds value to what we present. We also assessed implementation with limited time, i.e., the ideal would probably be to do so with more time in terms of developing standards and indicators. However, given the hypothetical difficulties that centres might encounter, we decided to bring this date forward a few months to be able to help as soon as possible in the event of any difficulties, and not lose out to the inertia of a project that is starting up. It is possible that readers might notice that we have not defined standards and indicators of efficiency. We should point out that they were selected to be as realistic as possible, however, bearing in mind that we should aspire to maximum care quality standards, we are sure that this will change soon to include “hard” standards of efficiency. Finally, we did not perform an analysis tailored to the specific data of the centres; this will be done in further analyses of this project.

In sum, in the NEXUS 2.0 project we have continued to work in disseminating and implementing multidisciplinary care models of quality for patients with PsA but tailored to the characteristics and circumstances of our national health system. Therefore, one of the most relevant contributions of the NEXUS project has been to create tools to ensure homogeneous, patient-focussed practice that are based on best evidence and experience and are able to define essential requirements to clinical excellence. This system will also enable self-evaluation for continuous improvement in multidisciplinary care. Therefore, we are fully confident that everything generated in this project will be decisive in achieving clinical excellence in the care of patients with PsA.

FinancingThe project was funded through the Rey Juan Carlos University.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To doctors Javier Calvo Cátala, Cristina Campos Fernández, Amalia Rueda Cid, Manuel Velasco Pastor, Juan José Lerma Garrido, Dolores Pastor Cubillos, Angels Martínez Ferrer, Almudena Mateu Puchades, Gerard Pitarch, Encarna Montesinos Villaescusa, Juan Alberto Paz Solarte, Maite Abalde, Jose A. Mosquera, Jose Álvarez, Luis Fernández, Javier Concheiro, Jesús Ibáñez, Marisa Cristina Cáceres Cwiek, Laura Cuesta Montero, Laura García Fernández, Pedro Lloret Luna, Rafael Rojo España, Carolina Pereda Carrasco, Paloma Sánchez-Pedreño Guillén, Caridad Soria Martínez, Carmelo Tornero Ramos, María Rosario Oliva Ruiz, Rafael Méndez, María José Moreno Martínez, Luis Francisco Linares Ferrando, Manuel José Moreno Ramos, Encarnación Pagán García, Neus Alicia Quilis Marti, Ana M. Carrizosa Esquivel, Juan Povedano Gómez, Gustavo Adolfo Añez Sturchio, María Picazo, Azucena Hernández Sanz, Cristina Schoendorff Ortega, Prudencio Ambrojo Antunez, Remedios Llorente Suárez, Francisco Domínguez de Luis, Antonio Cardenal Escarcena, Maria Torresano Andrés, Manuel Maqueda López.

Please cite this article as: Queiro R, Coto P, Joven B, Rivera R, Navío Marco T, de la Cueva P, et al. Estado actual de la atención multidisciplinar para pacientes con artritis psoriásica en España: proyecto NEXUS 2.0. Reumatol Clin. 2020;16:24–31.