Gout is a crystal arthropathy that is associated with significant loss of quality of life. A treat-to-target approach and proactive monitoring yield superior outcomes to standard care. The Clinical Nurse Specialist enhances follow-up and adherence to treatment in patients with gout, improving their perceived healthcare quality.

ObjectiveTo determine the factors that affect the perceived quality and satisfaction of patients with gout treated in a rheumatology clinic and to identify areas for improvement, as well as to explore the influence of nurses’ work in the care and management of these patients.

MethodsCross-sectional observational study in patients with gout monitored in a monographic clinic by anonymous survey based on the SERVQUAL quality model, with demographic data and questions about aspects of care.

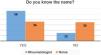

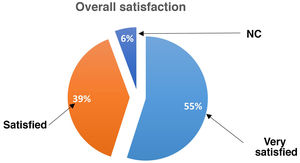

Results71 completed surveys were collected from the 80 delivered between August 2019 and January 2020. Most of the participants were males over 45 years of age. A total of 39% were satisfied with the care received, and 55% were very satisfied. All the respondents were satisfied with the face-to-face consultation with the Clinical Nurse Specialist and 66% considered the telephone consultation with the nurse to be good. Possible areas for improvement (referral time to consultation, identification, and availability of health providers) were identified.

ConclusionWe found high overall satisfaction perceived by the patients attended in a gout consultation with the Clinical Nurse Specialist. Understanding and systematizing the patients’ opinion is essential to improve clinical care.

La gota es una artritis cristalina que se asocia con pérdida importante de calidad de vida. Un tratamiento por objetivos y un seguimiento proactivo permiten obtener mejores desenlaces clínicos. La enfermería especializada en reumatología optimiza el seguimiento en pacientes con gota y la adherencia al tratamiento, pudiendo mejorar la calidad percibida de estos enfermos en relación con la atención sanitaria.

ObjetivoDeterminar Determinar los factores que afectan a la calidad percibida y a la satisfacción de los enfermos con gota atendidos en consultas de reumatología e identificar áreas de mejora, así como explorar la influencia de enfermería en la atención y el seguimiento de estos pacientes.

MetodologíaEstudio observacional transversal en pacientes con gota seguidos en una consulta monográfica mediante encuesta anónima basada en el modelo de calidad SERVQUAL, con datos demográficos y preguntas sobre aspectos asistenciales.

ResultadosSe recogieron 71 encuestas cumplimentadas de las 80 entregadas entre agosto de 2019 y enero de 2020. La mayoría de los participantes fueron varones de más de 45 años. El 39% se mostraron satisfechos con la atención recibida, y el 55% muy satisfechos. Todos los encuestados se mostraron satisfechos con la consulta presencial conjunta con enfermería especializada en reumatología, y el 66% consideraron buena la consulta telefónica con el enfermero. Se identificaron posibles áreas de mejora (tiempo de derivación a consulta, identificación y disponibilidad del personal sanitario.

ConclusiónEncontramos una alta satisfacción global percibida por los pacientes atendidos en consulta de gota con enfermería especializada en reumatología. Conocer y sistematizar la opinión de los pacientes es esencial para mejorar la atención ofrecida.

Gout is a systemic metabolic disease resulting from the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in tissues. In addition to producing painful and often disabling inflammatory joint attacks, it also has significant cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic implications1. It is a chronic disease that entails significant socio-occupational costs and is associated with loss of quality of life and increased morbidity and mortality, especially in patients with severe gout2–4.

However, it has been proven that correctly treating gout can have a positive impact on these aspects, with lower mortality in patients who achieve the recommended urate target (<6 mg/dl)5. Similarly, urate lowering therapy (ULT) improves the quality of life of these patients6. Furthermore, several studies have shown that proactive gout monitoring improves adherence, which is related to better clinical outcomes7. On these lines, in the last decade several investigators have explored the role of the Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) in monitoring gout, and have achieved overall very positive results in the global management (>90% of patients with target uricaemia, >95% adherence to ULT, significant reduction in attacks and in the number and size of tophi, substantial improvement in quality of life and knowledge of the disease, savings in quality-adjusted life years)8,9 and cardiovascular management (better control of traditional risk factors, positive trend in reduction of estimated risk at 5 years) of the disease. In a disease that has such low adherence to treatment (less than 50% overall), CNS intervention has been proposed to help modify aspects related to the patient (knowledge and awareness of the disease, motivation, behaviour changes)11,12.

Satisfaction surveys are a very useful tool for measuring patients’ perception of care quality. They help not only to ascertain the degree of patient satisfaction with the care received, but also to detect aspects in need of correction and elements that need to be improved. This makes the service offered more attractive to patients so that they return to receive the care they need13,14. There are national studies showing higher patient-perceived quality and better clinical outcomes in rheumatology services with nursing staff15,16. However, to date, no study of perceived quality has been published in Spain that focuses on gout patients seen in a consultation with a CNS.

The aim of this study was to determine the factors affecting the perceived quality and satisfaction of gout patients attended and to identify areas for improvement, and to explore how the role of the nurse influences the care and follow-up of these patients in rheumatology practice.

Material and methodsStructure of the nursing consultationIn 2018, a dedicated CNS gout clinic was implemented in the rheumatology department of the Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor, including a structured protocol of visits (Table 1). Patients are referred to this clinic through different channels: primary care, emergency and other of the centre’s medical and surgical departments (outpatient and inpatient). From the initial visit, we apply the treat-to-target (T2T) therapeutic strategy in accordance with international recommendations, aiming to maintain serum urate (SU) levels <6 mg/dl (<5 in tophaceous or severe gout)17. Patients can contact and access the service in the event of an attack, side effects or with any concerns, and they are encouraged to take part in therapeutic decision-making. The CNS provides health education and offers printed material explaining the disease and treatment to the patient and the people accompanying them, along with leaflets with advice on diet and healthy lifestyle habits. They also record and monitor vital signs and anthropometric measurements, and laboratory tests. They directly monitor blood pressure, smoking, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle, and actively monitor analytical parameters such as SU, liver and kidney function, cholesterol, triglycerides, glycaemia, and glycosylated haemoglobin. They establish pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures, seeking the collaboration of the patient, their relatives, and friends, and that of other specialties (primary care, cardiology, pulmonology, internal medicine, endocrinology, and nutrition).

Structured visit protocol for gout patients in the rheumatology clinic with the clinical nurse specialist.

| Visit | Modality | Staff | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Face-to-face | Rheumatologist and nurse | History taking, examination, blood pressure, anthropometric measures |

| Introduction to treatment, approach to comorbidities, health education | |||

| 2nd (one month after the first) | Telephone | Nurse | Monitoring of adherence to medication, side effects and gout attacks |

| Blood pressure monitoring | |||

| Encouraging healthy lifestyle habits and therapeutic adjustment | |||

| 3rd (3−6 months after the first) | Face-to-face | Rheumatologist and nurse | Targeted questioning |

| Examination | |||

| Therapeutic adjustment | |||

| Reinforcing health education | |||

| 4th (12 months after the first)a | Face-to-face | Rheumatologist and nurse | Targeted questioning |

| Examination | |||

| Therapeutic adjustment | |||

| Reinforcing health education |

A cross-sectional observational study using a survey based on the SERVQUAL quality questionnaire model, with demographic data and questions on care aspects (Appendix B Supplementary material)18. This study, with the informed consent of all participants, was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor (HUIL-R050-20).

The questionnaire was developed jointly with the nurse in charge of the consultation, using as a model quality surveys used in previous rheumatology service publications19. Inclusion criteria: patients aged ≥18 years and diagnosed with gout (ACR/EULAR 2015 criteria20 and/or demonstration of urate crystals in synovial fluid examination with optical microscopy) who agreed to answer the surveys anonymously and voluntarily, with a follow-up period of at least 6 months in our department’s dedicated clinic. Any reason that prevented the patient from understanding or correctly completing the survey was the only exclusion criterion.

In the first phase, the survey was collected, and the information was transferred to the electronic data collection notebook. A descriptive statistical analysis was then performed, expressing the absolute values and percentages of the qualitative variables collected in the questionnaires.

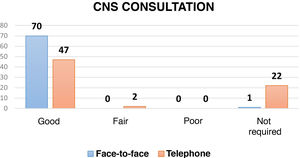

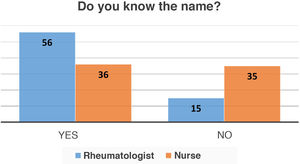

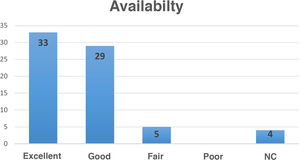

ResultsOf the 80 surveys that were distributed between September 2019 and September 2020, 71 were returned correctly completed. Of the patients who responded to the survey, 85% were male. Most were over 45 years of age: 52% were aged 46–60 years, 35% over 60 years. All the respondents were satisfied with the joint face-to-face consultation with the CNS and 66% considered telephone consultation with the nurse to be good (Fig. 1). Sixty-two percent considered the referral time to consultation reasonable, while 18% found the referral time too long (Fig. 2). Forty-nine percent of the patients admitted not knowing or not remembering the name of the nurse, compared to 21% who did not know the name of the rheumatologist (Fig. 3). Ninety-four percent felt that sufficient time was devoted to explanations and questions. The availability of the nurse and rheumatologist was considered good by 41%, and excellent by 46% (Fig. 4). In terms of overall satisfaction, 39% were satisfied with the care received at the gout clinic, and 55% were very satisfied (Fig. 5). A free text box at the end of the survey was used to collect different suggestions or complaints from patients regarding aspects of the care received and the healthcare staff in charge of the gout clinic. Although some stressed improving referral times from primary care to the rheumatology clinic, most of the opinions collected were related to other aspects, such as the waiting room or the staffing of the department.

DiscussionThis is the first study conducted to date in Spain on perceived quality in patients with gout seen in a CNS clinic. From our results, we highlight the high degree of acceptance by patients of the CNS in the gout clinic, and the high level of satisfaction with the availability of care and the time devoted to explanations about the disease and treatment. This reinforces the added value of this nurse in the management of this chronic disease.

Nurses have been present in Spanish rheumatology services for more than four decades21, and their level of professionalisation and specialisation has progressively increased; they have acquired a greater number of care and research competencies in recent years22. Together with the T2T strategy, they comprise a pillar on which to base interventions to improve gout treatment adherence11. This is key, as although gout is one of the most prevalent and disabling rheumatological conditions, with increased mortality compared to the general population, it has low therapeutic adherence12 and losses to follow-up of up to 50%23,24.

The design of the structure and dynamics of our gout clinic builds on previous work by investigators in other countries who have demonstrated how the management of gout patients can be improved by involving specialist nurses. Doherty et al.9 demonstrated in a clinical trial the efficacy of combining nursing intervention with the T2T strategy in gout, a higher number of patients achieving their SU target than with the therapeutic approach with their usual general practitioner (95% vs. 30% after 24 months; RR: 3.18; 95% CI: 2.42–4.18; P < .0001), and better outcomes in terms of cost-effectiveness (savings >£5000 per quality-adjusted life year). A later study by the same group with interviews with participants in this trial concludes that the keys to improved adherence achieved by nurses were patient education about gout and its treatment, greater knowledge about the benefits of treatment, and encouraging patient participation in therapeutic decision-making25. The NOR-Gout study by Uhlig et al.26, combining nurse intervention and ULT (at 12 months, 85% of patients achieved target uricaemia), also shows good results. For all these reasons, we included education with the CNS in our visits (especially in the first visit) and followed a T2T strategy placing the patient at the core.

Our results are consistent with international studies, such as that of Fuller et al.27, in which participants treated by the CNS showed greater satisfaction with the healthcare received compared to that of the general practitioner (outperformed by the CNS in satisfaction rates; 41%–63% preferred treatment by a nurse versus 5%–20% by a general practitioner), better knowledge of the disease, fewer gout attacks, and greater adherence to ULT (92.7% versus 76.6%; RR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.09–1.30; P < .001). At the national level, regarding how well CNS care is perceived, we present figures for gout (100% for face-to-face, 66% for telephone) like the overall figures for rheumatology patients of Garrido et al.19 (76% for face-to-face or telephone). We obtained positive responses in relation to perceived availability and explanations offered by the CNS, with percentages (good or excellent availability, 87%; sufficient time for explanations, 94%) like those of Garrido et al. for their patients (sufficient availability, 92%; satisfactory explanations, 96%). These data are relevant, as other studies suggest nurses need more time to offer gout patients the care they require28.

Our study also highlights the role of the CNS in monitoring traditional cardiovascular risk factors in gout patients, as recommended by national and international rheumatological scientific societies. Ours is consistent with other studies, such as that of McLachlan et al.10, which have shown very positive contributions by nurses at the cardiovascular level in gout (smoking cessation, improvement in blood pressure and physical activity figures, etc.). In fact, the role of the CNS is becoming increasingly evident at the European level in the management of cardiovascular risk in inflammatory joint disease29.

Although our study is limited to a single centre, it has several strengths: high participation, with a higher percentage of respondents (88.8%) than other publications (Rees et al.8, 55%; Fuller et al.27, 81,7%); it offers a global view of the "T2T consultation" for gout and positive patient feedback, and from it we can extract aspects that could be improved. These include shortening referral times by working together with primary care and other specialists, as one in five patients still find them excessively long, similar to that reported in other clinics (Garrido et al.19, 24%); optimising telephone contact (only 3% considered telematic consultation to be regular, but one in three answered "DK/NC", with comments such as "they have not called me"); making our nametags more visible and legible and introducing ourselves to the patient, as one in two does not know the name of the nurse and one in five does not know the name of the rheumatologist, similar to that published by Garrido et al.19 (20% do not know the name of the rheumatologist).

Future lines of work include studying the influence of CNS intervention on clinical outcomes and adherence to treatment in our cohort. We hope that our experience will serve as an example and stimulus to encourage nurse participation in the care of patients with gout in rheumatology clinics.

ConclusionsWe found a high degree of satisfaction among patients with gout monitored in the clinic, with very positive assessment of face-to-face and telephone care with the rheumatology specialist nurse, and the availability of the staff, and their ability and dedication in addressing concerns and offering explanation.

Quality of care indicators are important instruments to guide healthcare staff in managing patients with gout. Knowing and systematising patient feedback is essential to improve the care provided. This builds trust, improves communication and expectations, and can help to optimise adherence to treatment and follow-up.

We must work to improve on our availability, especially at the telematic level, and to identify the healthcare professionals attending patients, and the time it takes for patients to be referred to us.

All of this helps us to provide patients with a better experience in their relationship with the hospital and helps to empower them.

FundingNo funding was received for this funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank Dr Marta Novella for her critical reading of the draft manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Calvo-Aranda E, Sánchez-Aranda FM, Cebrián Méndez L, Matías de la Mano MÁ, Lojo Oliveira L, Navío Marco MT. Estudio de calidad percibida en pacientes con gota atendidos en una consulta de reumatología con enfermería especializada. Reumatol Clín. 2022;18:608–613.