Avascular hip necrosis (AHN) is characterized by the death of osteocytes and of the bone marrow caused by interruption of the blood supply to the femoral head.1–3

It commonly affects young adults.2,4,5 In the United States, the incidence is estimated to be between 10,000 and 30,000 cases each year, accounting for 5%–12% of the total hip arthroplasties performed to treat patients who have AHN.2,4,6–8 Despite the identification of a number of risk factors (RF), the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease remain unclear. A number of proposals have been made, including ischemia, direct cell toxicity and changes in the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells.4,6

Given the impact of this disease, which has an insidious onset and shows no clear symptoms or signs, it is necessary to be aware of those RF that promote it in order to maintain our vigilance in these patients. That will enable early diagnosis and the establishment of the necessary preventive measures and the proper treatment strategies.1,2

On this basis, the objective of our study was to estimate the prevalence of the different RF for AHN in patients admitted to Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre in Madrid, Spain. We included, from January 2010 to December 2015, a total of 129 patients with a diagnosis of AHN. The mean age±standard deviation was 58.35±15.33 years; 56.6% were men. The diagnostic criteria to define the presence of AHN were mainly obtained from the results of imaging studies. The study was approved by the clinical research ethic committee of our hospital.

The most prevalent RF were tobacco use (n=57; 44.2%) and dyslipidemia (n=46; 35.7%), which we consider to be associated. Among the RF with the greatest etiological burden for the development of AHN, the most prevalent were corticosteroid therapy (n=37; 28.7%), alcoholism (n=26; 20.2%) and previous traumatic injury (n=20; 15.5%). Of the 18 patients (13.9%) with autoimmune and/or inflammatory disease, 3 (16.7%) had systemic lupus erythematosus. The 3 were being treated with corticosteroids and 2 of the 3 were positive for antiphospholipid antibodies. In this respect, Gontero et al.9 found no differences in the total accumulated dose, daily dose and duration of steroid therapy or the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies.

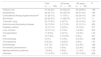

In 17 patients (13.2%), no RF was identified (Table 1). However, there were patients with several RF, with an accumulation of up to 6 in 1.6%. The most prevalent finding was 2 and 3 RF associated with 32 cases (24.8%) and with 27 cases (20.9%), respectively.

Risk Factors for Avascular Hip Necrosis.

| Total (n=129) | ≤50 years (n=46) | >50 years (n=83) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco use | 57 (44.2%) | 24 (52.2%) | 33 (39.8%) | .198 |

| Dyslipidemia | 46 (35.7%) | 20 (43.5%) | 26 (31.3%) | .184 |

| Corticosteroid therapy/hypercortisolisma | 37 (28.7%) | 17 (37%) | 20 (24.1%) | .155 |

| Alcoholism | 26 (20.2%) | 13 (28.3%) | 13 (15.7%) | .11 |

| Traumatic injury | 20 (15.5%) | 4 (8.7%) | 16 (19.3%) | .133 |

| Autoimmune/inflammatory disease | 18 (13.9%) | 8 (17.4%) | 10 (12.1%) | .434 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13 (10.1%) | 3 (6.5%) | 10 (12%) | .377 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 13 (10.1%) | 6 (13%) | 7 (8.4%) | .543 |

| Transplantation | 11 (8.5%) | 4 (8.7%) | 7 (8.4%) | 1.00 |

| HIV | 10 (7.8%) | 5 (10.9%) | 5 (6%) | .327 |

| Chemotherapy | 9 (7%) | 6 (13%) | 3 (3.6%) | .068 |

| Thrombophilia | 8 (6.2%) | 3 (6.5%) | 5 (6%) | 1.00 |

| Radiotherapy | 6 (4.7%) | 4 (8.7%) | 2 (2.4%) | .186 |

| Pro-embolic phenomenon | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.4%) | .538 |

| Myeloproliferative syndrome | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1.00 |

| Unknown | 17 (13.2%) | 1 (2.2%) | 16 (19.3%) | .006 |

The sample was divided into 2 groups to study the differences between the younger and older patients, randomly setting 50 years as the cutoff point. We found that there was an absence of known RF in the individuals over 50 years of age, resulting in a statistically significant difference (P=.006).

As other authors have indicated, this disease has a gradual onset, without specific symptoms or signs, meaning that the diagnosis is established late.2 Malizos et al.2 mention that, given the numerous associated factors that have recently been described, it is now less common to classify osteonecrosis as idiopathic. The results of our study concur in terms of our findings in the group of patients aged 50 years or less (2.2%). The prevalence of idiopathic AHN in patients over the age of 50 years in our series (19.3%) is similar to that reported by other authors (20%–25%).1,8,10 It is certain that, although this study is retrospective, it has its limitations. For example, missing information because these RF are not recorded in the medical records, contributing to the number of patients without associated factors. In our series, the most prevalent of the RF associated with AHN were tobacco use, dyslipidemia, corticosteroid therapy and alcoholism. Knowledge and detection of the RF associated with this disease will aid in taking preventive measures to delay its development and improve the prognosis.

Please cite this article as: de Sautu de Borbón EC, Morales Conejo M, Guerra Vales JM. Prevalencia de los factores de riesgo para el desarrollo de necrosis avascular de cadera en un hospital de tercer nivel. Reumatol Clin. 2018;14:122–123.