Recent data published on biological therapy in axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) since the last publication of the recommendations of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER) has led to the generation of a review of these recommendations based on the best possible evidence. These recommendations should be a reference for rheumatologists and those involved in the treatment of patients with axSpA.

MethodsRecommendations were drawn up following a nominal group methodology and based on systematic reviews. The level of evidence and grade of recommendation were classified according to the model proposed by the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine at Oxford. The level of agreement was established through the Delphi technique.

ResultsIn this review, we did an update of the evaluation of disease activity and treatment objectives. We included the new drugs with approved therapeutic indication for axSpA. We reviewed both the predictive factors of the therapeutic response and progression of radiographic damage. Finally, we drafted some recommendations for the treatment of patients refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor, as well as for the possible optimisation of biological therapy. The document also includes a table of recommendations and a treatment algorithm.

ConclusionsWe present an update of the SER recommendations for the use of biological therapy in patients with axSpA.

La aparición de nueva información sobre las terapias biológicas en la espondiloartritis axial (EspAax) ha impulsado una nueva revisión de las recomendaciones de la Sociedad Española de Reumatología (SER) basadas en la mejor evidencia posible. Estas nuevas recomendaciones pueden servir de referencia para reumatólogos implicados en el tratamiento de estos pacientes.

MétodosSe creó un panel formado por nueve reumatólogos expertos en EspAax, previamente seleccionados por la SER mediante una convocatoria abierta. Las fases del trabajo fueron: identificación de las áreas clave para la actualización del consenso anterior, análisis y síntesis de la evidencia científica (sistema modificado de Oxford, CEBM, 2009) y formulación de recomendaciones a partir de esta evidencia y de técnicas de consenso.

ResultadosEsta revisión de las recomendaciones comporta una actualización en la evaluación de actividad de la enfermedad y objetivos de tratamiento. Incorpora también los nuevos fármacos disponibles, así como sus nuevas indicaciones, y una revisión de los factores predictivos de respuesta terapéutica y progresión del daño radiográfico. Finalmente, estas recomendaciones abordan también las situaciones de fracaso a un primer anti-TNF, así como la posible optimización de la terapia biológica. El documento incluye una tabla de recomendaciones y un algoritmo de tratamiento.

ConclusionesSe presenta la actualización de las recomendaciones SER para el uso de terapias biológicas en pacientes con EspAax.

This document is the third update of the consensus of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER) on the Use of Biological Therapies in Axial Spondyloarthritis (AxSpA). It includes recommendations intended for use as benchmarks to help and improve therapeutic decision-making by rheumatologists, and across the various care and management levels involved in the treatment of this disease. Due to their high cost and safety margins, use of BT must be rational and thoughtful, based on solid evidence, well-designed studies, registry results, and accumulated experience. Treatment with BT must be included in a broad therapeutic strategy for the disease, considering all potential pharmacological and non-pharmacological actions, and taking the opinion of the patient into account.

AxSpA is characterised by involvement of the sacroiliac joints and spine. Diagnosis was traditionally based on the 1984 Modified New York criteria for ankylosing spondylitis (AS) that require the presence of chronic, irreversible structural damage to the sacroiliac joints, detectable on plain radiography, and involved significant diagnostic delay. The recent publication in 2009 of the Assessment of Ankylosing Spondylitis International Society (ASAS) criteria has improved the classification of patients with spondyloarthritis (SpA) in general and has enabled the inclusion of patients in the earlier stages of the disease. These published criteria define the AxSpA group of patients with predominantly axial symptoms but who might also have peripheral symptoms, as well as the peripheral SpA group.1

AxSpA includes patients with AxSpA who also have radiographic sacroiliitis (AS defined according to the modified New York criteria), along with individuals with non-radiographic AxSpA (nr-AxSpA). Although there is still intense debate as to whether these are two different entities or a single entity with different clinical phenotypes, following the recent EULAR recommendations, we will consider it a single entity in this document.2

The group of SpA has major social and health impact. In general, the prevalence in Spain is between .1% and 2.5% of the population. There is an estimated incidence of between .84 and 77 cases per 100,000 inhabitants4 per year, which counts for 13% of the patients in Spanish rheumatology departments. A considerable number of patients with AxSpA develop debilitating disease, with impaired functional capacity and quality of life, even from the onset of the disease, resulting in a loss of productive capacity.5

Although education, physical therapy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) remain the mainstay of treatment for AxSpA, the evidence for the efficacy of TNFα antagonists for all aspects of the disease is notably increasing.6 There are no data to support the preferential use of one NSAID over another, although those with a long half-life tend to be used in clinical practice. Specific cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors are a very effective group of anti-inflammatory drugs and therefore should be taken into consideration in the treatment of these patients.7–9 The published studies do not support the use of any of the traditional disease-modifying drugs (DMARDs) for axial manifestations of the disease. Sulfasalazine has proved to be effective in controlled studies, although to a moderate extent, for peripheral joint manifestations.10 There are no controlled studies that support the efficacy of other DMARDs, such as methotrexate or leflunomide for peripheral joint manifestations, although their use for the peripheral forms cannot be discounted in clinical practice.3

Material and MethodsIn this project we used a qualitative synthesis of the scientific evidence and consensus methods (“reasoned judgement” and “modified Delphi”) to express the agreement of experts based on their clinical experience and scientific evidence.

Phases of the ProcessThe drafting phases of the Recommendations document are outlined as follows:

- 1.

Creation of the working group. The drafting of the document started with the formation of a panel of experts chosen through an open call to all members of SER. The SER Clinical Practice Guidelines and Recommendations Commission assessed the applicants’ curriculum vitae according to objective criteria regarding their contribution to the knowledge of AxSpA, principally through participating in publications in journals of impact over the past 5 years. The final panel of experts comprised 9 SER member rheumatologists. One of these rheumatologists, as the principal investigator, and a methodology specialist from SER's Research unit coordinated the clinical and methodological aspects.

- 2.

Identification of the key areas for updating the previous consensus. All the members of the working group participated in structuring the document and establishing the contents and key aspects. It was decided that the recommendations of the previous Consensus and those of the last version of ESPOGUIA 20153 should be updated. The clinical questions that might most affect use of BT for AxSpA were identified first, and then the content and results that did not need to answer the research question formulation. The methodology to be used in the process for drawing up the recommendations was also defined.

- 3.

Literature search. The clinical questions were reformulated into four questions in PICO format. A search strategy was designed to answer the questions, and a review of the scientific evidence in studies published up until February 2016. The databases used were: PubMed (Medline), EMBASE, and Cochrane Library (Wiley Online). The process was completed with a manual search of references and posters, and conference abstracts that the reviewers and experts considered of interest. The literature search strategies of the seven systematic reviews (SR) can be found in Supplementary material (in a methodological appendix on the SER website).

- 4.

Analysis and synthesis of the scientific evidence. Six rheumatologists, from the SER working group of evidence reviewers, oversaw the systematic review of the available scientific evidence. After critical reading of the full text of the studies chosen for each review, they prepared an abstract using a standardised form including tables and text to describe the methodology, the results, and the quality of each study. The reasons were detailed for excluding the articles that were not included in the selection. The overall level of scientific evidence was evaluated using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (CEBM) modified levels of evidence (http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009).

- 5.

Formulation of recommendations. On completion of the critical reading, the principal investigator and the group of experts proceeded to formulate specific recommendations based on scientific evidence. This formulation was based on “formal evaluation” or “reasoned judgement”, summarising beforehand the evidence for each of the clinical questions. The quality, quantity and consistency of the evidence, the applicability and generalisability of the research results and their clinical impact were also considered. Two consensus rounds were used to formulate the general recommendations: first, in a face-to-face meeting, using the “reasoned judgement” consensus system, all the experts drafted and discussed the recommendations in the presence of the methodologist; then, using a Delphi questionnaire, the experts’ level of agreement was agreed with the drafting of each of the recommendations using a Likert scale of 1–5 (1: strongly disagree, 2: moderately disagree, 3: neither agree nor disagree, 4: moderately agree, 5: strongly agree). A high level of agreement was established when more than 75% of the panellists awarded scores ≥4 on the Likert scale. The level of evidence and the grading of the strength of the recommendations were established based on the modified Oxford system 2009. There were some comments to some of the recommendations (to which the level of evidence and degree of agreement were added) that the drafting group considered relevant to include as clarifications or consequences of what is expressed in the recommendation itself.

- 6.

Public exposure. The draft of this SER Recommendations document was put through a process of public exposure by the SER members, and by various interest groups (the pharmaceutical industry, other scientific societies and patient associations), for assessment and their scientific argumentation for the methodology or the recommendations.

The document sets out all the recommendations formulated and subdivided into two sections: general principles and specific recommendations. A therapeutic algorithm was prepared based on the recommendations presenting a summarised form of the treatment approach to AxSpA.

Previous ConsiderationsAvailable Biological TherapyTNF-alpha Inhibitor (Anti-TNF) DrugsThere are currently three monoclonal antibodies available to us (infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab), a fusion protein with the soluble p75 receptor (etanercept) and a PEGylated Fab’ fragment of a recombinant humanised monoclonal antibody (certolizumab pegol). The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has approved these drugs for both AS and nr-AxSpA, except for infliximab, which is only indicated for AS.11 These drugs have been demonstrated to improve not only the clinical symptoms of the disease, but also axial mobility, physical function, quality of life and biological inflammation parameters, as well as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein (CRP) the signs of vertebral and sacroiliac inflammation (seen on MRI).12,13 The response rate for all patients with AS is similar (ASAS20 58%–61% vs 10%–20% of the placebo), therefore the specific choice will depend on the clinician's judgement and each patient's particular circumstances.12,13 For more information, see the previous consensus14 and the table in Supplementary material.

Certolizumab (CZP)This is the most recently licensed anti-TNF that was not included the previous consensus. The recommended dose is 200mg every 2 weeks, or 400mg every 4 weeks subcutaneously. CZP has proven equally effective for patients with AS and those with nr-AxSpA in reducing the signs and symptoms of the disease.15,16 The safety profile was consistent with the safety data presented for other anti-TNF drugs. Due to the absence of the Fc region, CZP does not bind to human FcRn and consequently does not undergo the placental transfer that is mediated by the other monoclonal antibodies, and neither have significant levels of CZP been detected in breast milk.17

Biosimilar drugsA biosimilar is a biological drug that contains a version of the active substance of an original biological product that has already been licensed (benchmark drug). The development of biosimilars is not aimed at demonstrating a clinical benefit as such, but rather to demonstrate efficacy and safety similar to those of the benchmark drug.18,19 Because biosimilars are not exact copies of the benchmark biological agent, they occasionally require specific clinical trials for each of the benchmark drug's indications. Given the lack of published demonstration studies, interchangeability and therapeutic substitution of an original biological drug for a biosimilar should not be automatic or for purely financial reasons; the interest of the patient must prevail.18 Biosimilars should be used under strict pharmacovigilance follow-up programmes. Biosimilar infliximab and etanercept are the biosimilar drugs that are currently licensed by the EMA.

The licensed biosimilar infliximabs (three are already available to us)20–22 are Remicade® (infliximab) and they have the same indications, dosage and administration times as the benchmark drug. Like infliximab, they are not indicated for nr-AxSpA. Based on data provided by the industry, the EMA approved the biosimilar infliximabs for all the Remicade® indications, considering the data from trials performed on patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and AS,23,24 although they requested additional studies for them to be licensed for the treatment of Crohn's disease and ulcerating colitis.

The biosimilar etanercept (only one is currently available to us) was approved by the EMA for the same indications and circumstances as the benchmark drug (to treat AS and nr-AxSpA). The registry study (SB4-G31-AR) was performed on patients with RA, and the biosimilar indication extrapolated to all the indications and circumstances of the benchmark drug, including AS and nr-AxSpA.25

Anti-IL-17 DrugsSecukinumabThis is a fully human recombinant monoclonal antibody that targets IL-17ª.26 Secukinumab is indicated for the treatment of active AS in adults after an inadequate response to conventional treatment. In registry studies on the drug to establish their therapeutic indication, secukinumab had an ASAS20 response (primary objective at 16 weeks) of 59%, compared to 28% in the placebo group; these results were maintained until week 52, even in patients with a previous inadequate response to the anti-TNF drugs. An improvement was also achieved in ASAS40, BASDAI, CRP and quality of life.27 The persistence of the observed clinical response was confirmed in an extension to 2 years, and that 80% of the patients treated with secukinumab showed no radiographic progression.28 Secukinumab can increase the risk of infections: most were mild or moderate upper respiratory tract infections that did not require discontinuation of the treatment. Care should be taken in evaluating administration of secukinumab in patients with chronic infections or a history of recurrent infections. The same recommendations as for the anti-TNF drugs apply to tuberculosis, although no cases of tuberculosis were reported in the clinical trials. An increased incidence of candidiasis mucocutaneous infections were observed with an adjusted rate of .9 per 100 patients, but these resolved with antifungal treatment without having to discontinue the secukinumab. Neutropenia (.3%) and hypersensitivity reactions (.6%) were observed infrequently and were mild in most cases. The immunogenicity profile seems to be very low (.7% development of antibodies at 52 weeks, almost half neutralising antibodies). There is insufficient evidence for the efficacy of anti-IL-17 for treating SpA-associated uveitis. Secukinumab did not prove effective for treating active moderate/severe Crohn's disease and showed a rate of adverse events above that of the placebo.29 Secukinumab is not contraindicated with congestive heart failure (CHF) or with demyelinating diseases. Finally, the currently available data do not suggest that secukinumab increases the risk of cardiovascular events or neoplasia. There is insufficient data on the use of secukinumab in pregnancy or hepatropic viruses (BHV and CHV), or its concomitant use with live vaccines. Therefore, in these situations, the same measures as for anti-TNF therapy should apply.

Potential Future TargetsThere are currently many molecules under study for indication in the treatment of AxSpA patients that will certainly add to our therapeutic arsenal. In the line of IL-23 and IL-17, ustekinumab (monoclonal antibody targeting the p40 subunit common to IL-23 and IL-12) is the only molecule with published preliminary data.30 With regard to the so-called “small molecules” or DMARDs with a specific therapeutic target, there is already published preliminary data for apremilast (selective oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor) and tofacitinib (oral Janus kinase inhibitor) for patients with SA.31,32

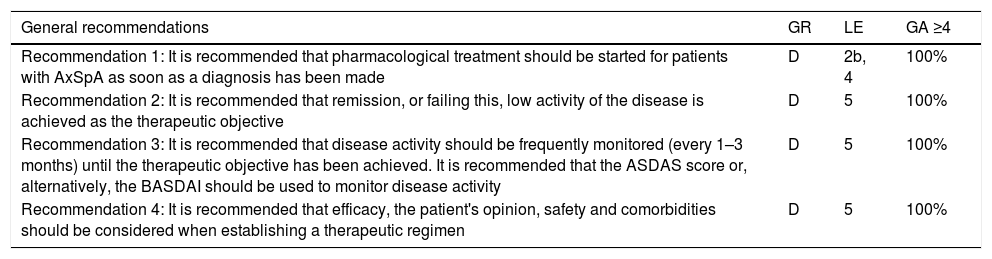

ResultsWe formulated a total of 14 recommendations on the use of biological therapies for AxSpA (Tables 1 and 2).

SER Recommendations on the Use of Biological Therapies for Axial Spondyloarthritis. General Recommendations.

| General recommendations | GR | LE | GA ≥4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation 1: It is recommended that pharmacological treatment should be started for patients with AxSpA as soon as a diagnosis has been made | D | 2b, 4 | 100% |

| Recommendation 2: It is recommended that remission, or failing this, low activity of the disease is achieved as the therapeutic objective | D | 5 | 100% |

| Recommendation 3: It is recommended that disease activity should be frequently monitored (every 1–3 months) until the therapeutic objective has been achieved. It is recommended that the ASDAS score or, alternatively, the BASDAI should be used to monitor disease activity | D | 5 | 100% |

| Recommendation 4: It is recommended that efficacy, the patient's opinion, safety and comorbidities should be considered when establishing a therapeutic regimen | D | 5 | 100% |

ASDAS: ASAS-endorsed disease activity score; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; AxSpA: axial spondyloarthritis; GA: grade of agreement; GR: grade of recommendation; LE: level of evidence.

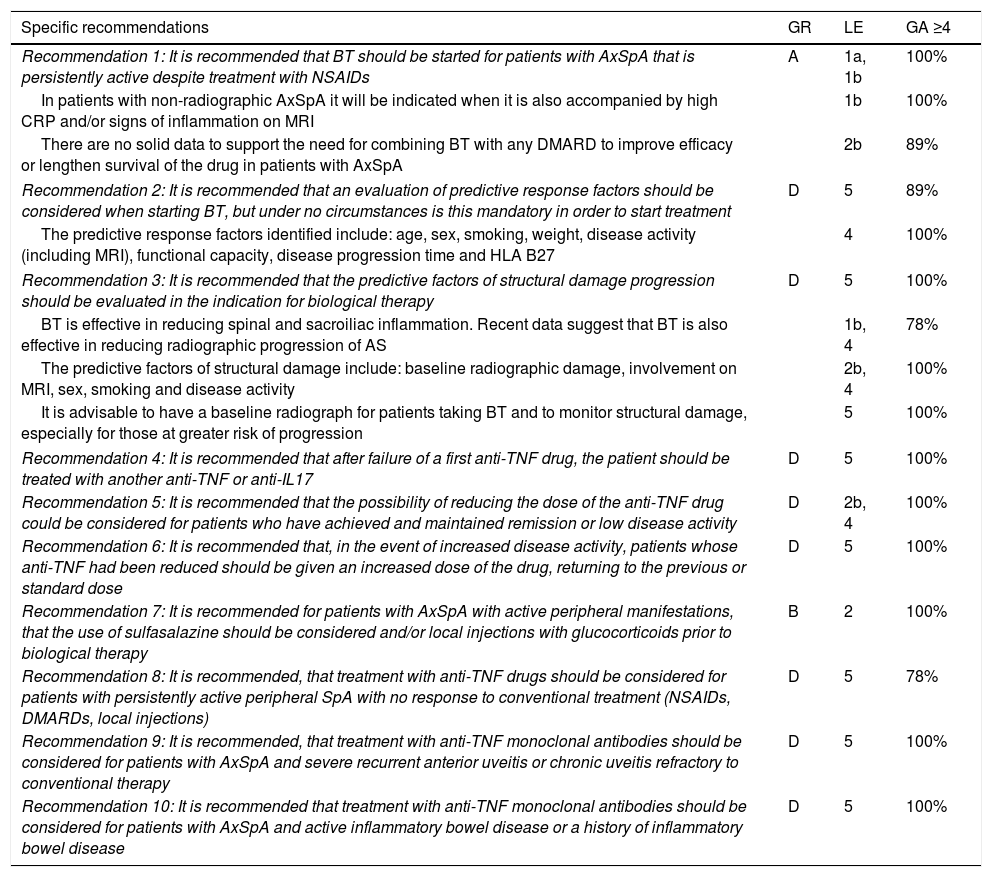

SER Recommendations on the Use of Biological Therapies for Axial Spondyloarthritis. Specific Recommendations.a

| Specific recommendations | GR | LE | GA ≥4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation 1: It is recommended that BT should be started for patients with AxSpA that is persistently active despite treatment with NSAIDs | A | 1a, 1b | 100% |

| In patients with non-radiographic AxSpA it will be indicated when it is also accompanied by high CRP and/or signs of inflammation on MRI | 1b | 100% | |

| There are no solid data to support the need for combining BT with any DMARD to improve efficacy or lengthen survival of the drug in patients with AxSpA | 2b | 89% | |

| Recommendation 2: It is recommended that an evaluation of predictive response factors should be considered when starting BT, but under no circumstances is this mandatory in order to start treatment | D | 5 | 89% |

| The predictive response factors identified include: age, sex, smoking, weight, disease activity (including MRI), functional capacity, disease progression time and HLA B27 | 4 | 100% | |

| Recommendation 3: It is recommended that the predictive factors of structural damage progression should be evaluated in the indication for biological therapy | D | 5 | 100% |

| BT is effective in reducing spinal and sacroiliac inflammation. Recent data suggest that BT is also effective in reducing radiographic progression of AS | 1b, 4 | 78% | |

| The predictive factors of structural damage include: baseline radiographic damage, involvement on MRI, sex, smoking and disease activity | 2b, 4 | 100% | |

| It is advisable to have a baseline radiograph for patients taking BT and to monitor structural damage, especially for those at greater risk of progression | 5 | 100% | |

| Recommendation 4: It is recommended that after failure of a first anti-TNF drug, the patient should be treated with another anti-TNF or anti-IL17 | D | 5 | 100% |

| Recommendation 5: It is recommended that the possibility of reducing the dose of the anti-TNF drug could be considered for patients who have achieved and maintained remission or low disease activity | D | 2b, 4 | 100% |

| Recommendation 6: It is recommended that, in the event of increased disease activity, patients whose anti-TNF had been reduced should be given an increased dose of the drug, returning to the previous or standard dose | D | 5 | 100% |

| Recommendation 7: It is recommended for patients with AxSpA with active peripheral manifestations, that the use of sulfasalazine should be considered and/or local injections with glucocorticoids prior to biological therapy | B | 2 | 100% |

| Recommendation 8: It is recommended, that treatment with anti-TNF drugs should be considered for patients with persistently active peripheral SpA with no response to conventional treatment (NSAIDs, DMARDs, local injections) | D | 5 | 78% |

| Recommendation 9: It is recommended, that treatment with anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies should be considered for patients with AxSpA and severe recurrent anterior uveitis or chronic uveitis refractory to conventional therapy | D | 5 | 100% |

| Recommendation 10: It is recommended that treatment with anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies should be considered for patients with AxSpA and active inflammatory bowel disease or a history of inflammatory bowel disease | D | 5 | 100% |

NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; anti-IL17: interleukin 17 inhibitor; anti-TNF: tumour necrosis factor inhibitor; AS: ankylosing spondylitis; AxSpA: axial spondyloarthritis; DMARDs: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; GA: grade of agreement; GR: grade of recommendation; HLA B27: human leucocyte antigen B27; LE: level of evidence; CPR: C-reactive protein; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; BT: biological therapy.

a The statements that are not in bold are corollaries derived from the immediately preceding recommendation.

General recommendation 1

It is recommended that pharmacological treatment should be started for patients with AxSpA as soon as a diagnosis has been made (GR: D; LE: 2b, 4; GA: 100%).

Early diagnosis appears to be key, since there are many studies that show that a delayed diagnosis results in poorer outcomes (BASDAI, BASFI, axial mobility, radiological progression).33–35

The NSAIDs and BT are the only drugs that have been demonstrated to be effective for treating axial manifestations. Several studies on patients with early AxSpA who have been given NSAIDs and anti-TNF therapy report encouraging results with a higher treatment response rate than studies performed on patients with more advanced disease and with defined AS.36 In this regard, several studies suggest that progression time is an important factor in predicting response to treatment,37,38 and in predicting clinical flare-up of the disease after discontinuing anti-TNF therapy.39 The data on reducing radiographic progression are controversial for both NSAIDs and BT. However, there is some evidence to suggest that when the treatment manages to maintain strict control of the disease (low disease activity) it can reduce radiographic progression in these patients.40

General recommendation 2

It is recommended that remission, or failing this, low activity of the disease should be achieved as the therapeutic objective (GR: D; LE: 5; GA: 100%).

General recommendation 3

It is recommended that disease activity should be frequently monitored (every 1–3 months) until the therapeutic objective has been achieved. It is recommended that the ASDAS score or, alternatively, the BASDAI should be used to monitor disease activity (GR: D; LE: 5; GA: 100%).

The treatment objective of AxSpA is to achieve remission of the disease or, failing this, to reduce the inflammatory activity to the maximum to achieve significant improvement of signs and symptoms (joint inflammation, pain, axial and peripheral rigidity, etc.), to preserve functional capacity, maintain a good quality of life, and to control structural damage.

Evaluation of Disease ActivityBecause AxSpA presents heterogeneously, and because various clinical manifestations can co-exist, the use of isolated variables to measure disease activity can give a false impression and therefore, it is recommended that composite indices should be used together with the physician's assessment to comprehensively demonstrate disease activity.41

The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) is traditionally used to monitor disease activity, and to indicate BT.42 Based on this index, remission of the disease is usually defined as BASDAI ≤2 and serum C-RP within the normal range. However, this is a difficult objective to achieve, and occasionally a BASDAI <4 can be considered acceptable (this is the cut-off point that is usually used to define low disease activity) together with a serum C-RP within the normal range. Nonetheless, the main limitation of the BASDAI is that it is a completely subjective index. Therefore, the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) was created in 2009, which includes subjective variables as well as an objective variable of inflammation.43 Since its publication, the ASDAS has been validated in different populations including a SpA cohort recently started in Spain.44 The discriminatory capacity and sensitivity to change of the ASDAS have also been demonstrated in many studies, and are superior to those of the BASDAI or any other isolated measurement.45 Moreover, the ASDAS has proved the clinical measurement tool that best relates to the degree of inflammation detected on MRI of the sacroiliac joints and spine, and to the degree of radiographic progression in longitudinal studies.40,46 In light of all of this, the members of the panel for this document recommend using the ASDAS-CRP as the main index for monitoring disease activity. Based on this scale, the therapeutic objective is to achieve an ASDAS-CRP <1.3. However, the panel considers that an ASDAS-CRP <2.1 could be considered acceptable.47

In any case, when assessing whether a patient with AxSpA has achieved remission or low disease activity, the physician's overall assessment as well as one of the composite indices (preferably the ASDAS) should be considered, preferably expressed on a visual analogue scale of 0.1 and based on clinical history-taking, physical examination, complementary tests, and the absence of extra-articular manifestations of the disease.

The role of MRI in monitoring disease activity in patients with AxSpA is yet to be defined. To date its added value compared to the composite clinical indices is unknown, and therefore its use is not routinely indicated to monitor disease activity. However, MRI of the sacroiliac joints and/or spine can be used to evaluate and monitor AxSpA disease activity in some cases, providing additional information to the clinical and biochemical assessments. The decision as to when to repeat MRI in these cases depends on the clinical circumstances.48

Assessment of Physical Function and Quality of LifeThe panel recommends using the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Function Index (BASFI) questionnaire to measure the functional capacity of patients with AxSpA.49 In special situations if peripheral arthritis predominates, the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) might be more appropriate.

The Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life (ASQoL) questionnaire has been used traditionally to evaluate the quality of life of patients with AxSpA. The ASAS group is currently developing a new health index, the ASAS Health Index (ASAS-HI), that comprises 17 questions and has been translated into Spanish; however, the cut-off points for defining the different health statuses are yet to be established.50

Definition of Active DiseaseWhen deciding a BT for patients with AxSpA, active disease is understood as a BASDAI ≥4 or alternatively an ASDAS-PRC ≥2.1, together with the physician's overall assessment that the disease is active (≥4 on VAS of 0–10cm) based on their experience, clinical history-taking, physical examination, and complementary tests.

Definition of Therapeutic ResponseA patient is considered to be responding to BT if after 3 months of treatment there is: (a) a reduction of the BASDAI of 50% or absolute reduction of more than 2 points compared to the previous values,37 or (b) reduction of the ASDAS ≥1.1 (clinically significant improvement).41 In patients who are refractory to BT and in the absence of a therapeutic alternative, a minimally acceptable response in order to continue with the drug will be an improvement of 20% compared to the baseline situation prior to starting the biological treatment. In any case and in all situations, the physician's opinion based on their experience and the patient's clinical data are essential when deciding whether to continue the treatment.

General recommendation 4

It is recommended that efficacy, the patient's opinion, safety and comorbidities should be considered when establishing a therapeutic regimen (GR: D; LE: 5; GA: 100%).

There are no direct comparative data that demonstrate differences in terms of efficacy and safety between the different anti-TNF drugs or between the different anti-TNF drugs and secukinumab.13,27 In this regard, the choice or one or other drug will be made in line with the recommendations of most of the guidelines,3,14 according to other factors associated with the administration features and particularities of each drug, such as the availability of a day hospital and the ease of intravenous cannulation, the patient's occupation (which might affect the possibility of receiving treatment as an inpatient), and the patient's personal preferences. Finally, it is important when prescribing a drug to bear in mind the presence of extra-articular manifestations and comorbidities.

NSAIDs are considered the cornerstone and initial treatment for patients with AxSpA. However, their continuous use has been associated with greater difficulty in controlling blood pressure and heart failure, impaired renal function, and increased mortality long term.51,52 Therefore, it is considered important to evaluate the cardiovascular risk profile and assess therapeutic alternatives when prescribing and chronically treating these patients with NSAIDs, particularly when there is evidence that anti-TNF treatment seems to reduce endothelial dysfunction, and might stabilise subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with AS.53,54

Specific Recommendations- 1.

It is recommended that BT should be started for patients with AxSpA that is persistently active despite treatment with NSAIDs (GR: A; LE: 1a, 1b; GA: 100%).

Comments about this recommendation:

In patients with non-radiographic AxSpA it will be indicated when it is also accompanied by high CRP and/or signs of inflammation on MRI (LE: 1b; GA: 100%).

There are no solid data to support the need for combining BT with a DMARD to improve efficacy or lengthen survival of the drug in patients with AxSpA (LE: 2b; GA: 89%).

Several studies indicate that the clinical manifestations and disease load in patients with nr-AxSpA and in defined AS are comparable.55,56 Therefore, both clinical phenotypes require treatment, irrespective of the presence of structural damage.

TNF inhibitors and secukinumab have proved effective in the treatment of AS refractory to NSAIDs, with significant reduction in clinical symptoms, inflammatory activity measured by CRP and/or MRI, functional capacity and quality of life,26,57–59 and there are even data to show a potential slowing effect associated with BT on radiographic spinal progression.33,60,61

The TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept and golimumab) have been demonstrated as effective in treating NSAID-refractory nr-AxSpA, with a significant reduction of clinical symptoms and improved functional capacity and quality of life, similar to that observed in patients with AS.16,62–64 An improved clinical response has also been observed in these studies in patients whose clinical symptoms were associated with high CRP and/or inflammation on sacroiliac MRI. Not all the patients with nr-AxSpA progressed to defined AS: various studies have shown that the presence of high CRP and sacroiliac inflammation measured by MRI are predictive factors of disease progression, and of response to anti-TNF therapy.63,65,66 In this regard, it is reasonable that patients with nr-AxSpA will require the clinical activity of the disease to be accompanied by a high CRP and/or sacroiliitis on MRI before establishing an indication for BT.

There are no data yet of the efficacy of infliximab or secukinumab in patients with nr-AxSpA, therefore these drugs are not licensed for this indication. There are no data on patients with AxSpA to support the need to combine BT (anti-TNR and/or secukinumab) with a DMARD to improve efficacy.12,13,26 Although the data on survival are more controversial, the panel formulating these recommendations consider that, as yet, these data are insufficient to support the systematic combination of BT with a DMARD.67–70

- 2.

It is recommended that an evaluation of predictive response factors should be considered when starting BT, but under no circumstances is this mandatory in order to start treatment (GR: D; LE: 5; GA: 89%).

Comments about this recommendation:

The predictive response factors identified include: age, sex, smoking, weight, disease activity (including MRI), functional capacity, disease progression time, and HLA B27 (LE: 4; GA: 100%).

Numerous studies have associated certain variables of the disease with a better response to treatment with anti-TNF drugs. Treatment started at a younger age and shorter progression time have been associated with a better response in patients with AS37,71–74 as well as in patients with nr-AxSpA.63,75 Greater disease activity at the start of treatment is one of the best predictive factors of a good response that is shown in most studies on patients with AS and on patients with nr-AxSpA.63,75 Various studies state that males will show a better therapeutic response.71,73,74 In contrast, females76 and greater disability at the start of treatment (elevated initial BASFI) would be associated with a poorer therapeutic response.37,72,74 Excess weight expressed as a high body mass index (BMI) has been associated in some studies with a poorer response to treatment, and an independent association has also been described between BMI >30 and treatment failure.76 Smokers have less reduction in disease activity (BASDAI, ASDAS), especially when the CRP is high, and poorer response to treatment, even if they are ex-smokers.77 There are contradictory data regarding HLA B27, although most studies indicate a better therapeutic response in B27-positive individuals.74 A recent study suggests that an early response to anti-TNF therapy is one of the factors most associated with a good response in the long term.78

There are currently no contrasted predictive factors available of response to treatment with secukinumab.

Many studies evaluate the usefulness of new biomarkers in improving the prediction of response to anti-TNF therapy. Calprotectin is one that shows better results, although to date none have demonstrated conclusive results.79

There are many factors associated with response to anti-TNF therapy. None of these factors, in isolation or in combination, enable safe prediction of the final observed response, therefore their absence should not impede starting BT. However, based on the results shown, it appears important to improve therapeutic response to BT that treatment should not be delayed in active patients even if they are being treated with NSAIDs, and that they should lead a healthy lifestyle (avoiding smoking and excess weight).

- 3.

It is recommended that the predictive factors of structural damage progression should be evaluated in the indication for biological therapy (GR: D; LE: 5; GA: 100%).

Comments about this recommendation:

BT is effective in reducing spinal and sacroiliac inflammation. Recent data suggest that BT is also effective in reducing radiographic progression of AS (LE: 1b, 4; GA: 78%).

The predictive factors of structural damage include: baseline radiographic damage, involvement on MRI, sex, smoking and disease activity (LE: 2b, 4; GA: 100%).

It is advisable to have a baseline radiograph for patients taking BT and to monitor structural damage, especially for those at greater risk of progression (LE: 5; GA: 100%).

The presence of baseline radiographic damage (syndesmophytes on spinal X-ray) is the most important predictive factor of progression.80,81 Other factors that have been associated with greater progression of radiographic damage are being male, smoking and, especially, persistent inflammatory activity of the disease (clinically evaluated by serum CRP levels and/or the presence of bone oedema on MRI).81,82

BT has shown an early effect of inhibiting spinal inflammation and SI evaluated by MRI that is already visible from 6 weeks after starting treatment. This effect is clearly better than that obtained with NSAIDs or sulfasalazine (SSZ).62,83–85 There is a “therapeutic window of opportunity” in the earlier stages of the disease (nr-AxSpA) where BT appears to be particularly effective in inhibiting foci of osteitis at the level of the SI or spine.86 Reduction of bone oedema after BT is correlated with control of clinical disease activity and CRP, particularly in nr-AxSpA. However, in the first studies at 2 years, the disappearance of bone oedema after BT with anti-TNF drugs, especially in patients with more advanced disease, was not shown to halt the appearance of foci of fat degeneration or the progression of structural damage (syndesmophytes).87–89 In this regard, there are data to support that the association of inflammation plus fat degeneration, or fat degeneration with no previous inflammation, are significantly associated with the formation of syndesmophytes after 5 years’ treatment with infliximab.90 Recent data, however, indicate that continuous treatment with anti-TNF drugs over periods of more than 4 years is associated with significant reduction in structural spinal damage assessed by plain X-ray (mSASSS).33,60 Structural damage progression was less the earlier treatment was started, especially in the case of <5 years’ disease progression, and the longer treatment with anti-TNF drugs was maintained.33

The data from the main trials of secukinumab assessed at 2 years seem to indicate that a reduction of osteitic damage is associated with the non-progression of fatty lesions, and reduced progression of structural damage at the level of the spine. The patients with greater radiographic progression risk factors (previous baseline syndesmophytes and high CRP) showed a higher reduction in progression.61 The data, which are encouraging, are still preliminary and require confirmation in clinical practice and over longer periods to assess potential differences with the anti-TNF drugs.

There is little information on radiographic progression and BT combined with NSAIDs. In a single study with 40 patients with AS, radiographic progression at 2 years assessed by mSASSS was lower in the combined treatment with anti-TNF+NSAID group than in the group treated with an anti-TNF alone.91 But the available data are still too preliminary and scarce to support systematically taking this therapeutic approach.

Because structural damage progression is one of the key factors in determining the degree of long-term disability,92 in patients with BT it is advisable to have a baseline radiograph and to monitor the structural damage radiologically, particularly for those at greater risk of radiographic progression. There is no consensus as to the frequency of radiographic monitoring, since this depends on the degree of disease activity among other many factors and is therefore usually left to the judgement of the physician. However, in active patients and in line with the recent EULAR48 recommendations, it seems reasonable to SASS monitor in periods of 2 years.

- 4.

It is recommended that after failure of a first anti-TNF drug, the patient should be treated with another anti-TNF or anti-IL17 (GR D; LE: 4; GA: 100%).

Treatment with a second anti-TNF drug or secukinumab for patients with AS where a previous anti-TNF has failed is effective in a high number of patients, although experience with secukinumab is still limited. Nonetheless, the clinical response observed is less than that of patients receiving a first biological drug.93–99 There are no data on differences in efficacy or survival between a change of anti-TNF or change of therapeutic target (secukinumab). Efficacy reduces with the use of successive biological treatments, but a response is still found after the third.93–99 There are data that suggest a better response in patients who change to a second anti-TNF due to secondary inefficacy or toxicity of the first compared to patients with a primary lack of response to the anti-TNF drug.

Survival of the drug was shorter after successive changes of anti-TNF93,97; however, the differences did not achieve statistical significance, possibly due to the small sample size. Although there do seem to be differences in survival in favour of changes made due to secondary inefficacy and toxicity compared to primary inefficacy.100 In the case of primary inefficacy of the anti-TNF agent, it would be reasonable to consider changing the therapeutic target and use secukinumab.

There is still no evidence regarding the efficacy of changing to an anti-TNF after failure with secukinumab, but the panel members consider it reasonable to use an anti-TF in these situations. The recommendation could have been formulated perhaps changing the term “first anti-TNF” to “first biological drug”, but at the time of drawing up this document there was no evidence or experience on failure with anti-IL-17A, and the subsequent use of an anti-TNF.

There is no data on changes of anti-TNF therapy for patients with nr-AxSpA, but we assume that the response would be no different from that of patients with AS.

No evidence was found on the efficacy of other biological drugs, such as rituximab or abatacept, after failure with anti-TNF therapy. There is no published data on ustekinumab.

- 5.

It is recommended that the possibility of reducing the dose of the anti-TNF drug could be considered for patients who have achieved and maintained remission or low disease activity (GR D; LE: 2b, 4; GA: 100%).

- 6.

It is recommended that, in the event of increased disease activity, patients whose anti-TNF had been reduced should be given an increased dose of the drug, returning to the previous or standard dose (GR: D; LE: 5; GA: 100%).

We found 13 studies in our systematic literature review on this subject.101–113 Few of these specified the time in remission of the disease before optimisation. However, most of the studies reported that this period varied between 6 months and one year,105,111–114 therefore it seems reasonable to ait for at least 6 months of disease remission before considering optimisation.

The recurrence rate in patients with AS for whom dose reduction strategies were used varied between 0% and 47%.101,102,104–106,108,109,111–113 Moreover, one recent study that was mentioned in the ACR conference of 2016115 showed that in patients with AS in clinical remission (BASDAI ≤2, with no arthritis or enthesitis and normal CRP) maintained for a minimum of 6 months, the treatment regimen with reduced doses of anti-TNF (approximately 40% of the standard dose) was not significantly inferior in terms of either efficacy or safety to the standard dose regimen.

There are no studies that specifically assess factors to predict outcomes after a BT dose reduction. Some indicate that a shorter duration of remission before dose reduction, shorter duration of treatment, and shorter duration of the disease are factors associated with recurrence.111 In contrast, a higher ASQoL score before optimisation, being male and not having received previous anti-TNF treatment were associated with a good response to optimisation.109,112 It is not considered a reasonable option to reduce BT in patients with AxSpA who have not achieved the therapeutic objective (remission or low disease activity), since the persistence of disease activity is the most important factor for clinical flare-up.

To date we only have results of optimisation with anti-TNF drugs. The long-term effects of reducing the BT dose on drug survival or structural damage are not known. Recent data suggest that patients with prior radiographic spinal damage receiving a reduced dose will progress more than those receiving full doses.116

There are too few data about optimisation in patients with nr-AxSpA to formulate an evidence-based recommendation. However, the same disease load of both populations55,56 and the similar response rate to BT observed in both populations16,62–64 would advise that nr-AxSpA patients should follow the same regimen as AS patients.

In most of the studies in which, after relapse, the doses prior to optimisation or standard doses were resumed, clinical response was recovered with response rates above 75%.104,106,109,112

There is no established definition of relapse, and different measurements have been used to establish flare-up of disease activity. The panel of experts considered any situation that involves a loss of the therapeutic target established at the start of treatment, either due to an increased BASDAI and CRP or an increased ASDAS, to be clinical flare. The panel also considers it essential when deciding how to manage this flare, either by readjusting the treatment with NSAID and/or restarting BT (returning to the dose prior to optimisation or to the standard dose), to take into account the physician's overall assessment of the flare and its circumstances (severity of flare, persistence over time and/association with other manifestations), as well as the opinion of the patient.

If reducing treatment is an option to be considered for patients who have achieved the therapeutic target and maintained it over a certain amount of time, discontinuing treatment is not an objective per se, and there are no data to support systematically taking this approach. Based on some series and isolated cases the possibility has been suggested of stopping treatment on an individual basis for patients who have achieved their therapeutic target and maintained it after reducing the biological treatment to the maximum.117 However, the data is currently too sparse to support this therapeutic approach.

- 7.

It is recommended for patients with AxSpA with active peripheral manifestations, that the use of sulfasalazine should be considered and/or local injections with glucocorticoids prior to BT (GR: B; LE: 2b; GA: 100%).

Between 30% and 50% of patients with AxSpA also have peripheral involvement in the form of arthritis, enthesitis or dactylitis, and there is a similar frequency among patients with AS and nr-AxSpA.118 In patients with AxSpA with stable axial symptoms but with active peripheral manifestations, particularly arthritis and dactylitis, treatment with NSAIDs and local glucocorticoid injections should be considered initially. In patients with enthesitis, if local injections are given, direct injection over the tendon should be avoided, especially the large tendons, such as the Achilles, patellar and quadriceps tendons.

The DMARDs have not proven their efficacy in the treatment of axial disease symptoms, and neither is there evidence to support their use in enthesitis. They might be indicated for patients with active arthritis who have shown intolerance or a lack of response to previous treatments. Sulfasalazine has been demonstrated to be effective in controlled studies, although only moderately, for joint manifestations at doses from 2 to 3g per day.119,120 There are no evidence-based recommendations to support treatment with other DMARDs such as methotrexate or leflunomide, and therefore the choice of drug will depend on comorbidities, the clinician's experience and the preferences of the patient. In any case, treatment with DMARDs should be maintained for at least 3 months before considering it to have been ineffective.

BT will be indicated for patients with AxSpA with active peripheral manifestations that do not respond to conventional treatment. The efficacy of the anti-TNF drugs and secukinumab has not only been demonstrated for patients with AxSpA with or without associated peripheral manifestations,26,121–123 but also for other forms of SpA where peripheral arthritis is the predominating clinical manifestation, such as psoriatic arthritis124,125 and inflammatory bowel disease-related arthritis.126

- 8.

It is recommended, that treatment with anti-TNF drugs should be considered for patients with persistently active peripheral SpA with no response to conventional treatment (NSAIDs, DMARDs, local injections) (GR: D; LE: 5; GA: 78%).

Patients with SpA of exclusively peripheral predominance comprise a specific subgroup, but if patients with psoriatic arthritis are excluded, the remainder, being a more clinically heterogeneous group, are not usually included in controlled clinical trials for the evaluation of new treatments. Therefore, there are few studies that assess the treatment of these patients; and the majority are not controlled clinical trials and are performed with small patient numbers. Although there are no specific studies with DMARDs, the results in patients with psoriatic arthritis with peripheral involvement, and clinical practice, suggest that they are useful. Several studies with adalimumab and golimumab, two of which are contrasted, clearly show that anti-TNF therapy is efficacious in these situations, although all of them had certain methodological limitations.127–129 The efficacy of treatment with anti-TNF drugs has also been observed in various observational studies performed on patients with reactive arthritis,130,131 which also enabled treatment to be stopped due to clinical remission in a third of the patients.131

There are no randomised controlled trials (RCT) in which other BT have been used, and neither are there any long-term studies to confirm the efficacy and safety of the anti-TNF drugs in patients with peripheral SpA. However, numerous RCT have been performed on patients with AxSpA and psoriatic arthritis that show that the different existing anti-TNF drugs are efficacious in treating peripheral arthritis, enthesitis and dactylitis.121–124 Therefore, anti-TNF treatment is recommended for patients with active peripheral SpAs that are refractory to conventional therapy including the DMARDs, as has been outlined in previous sections.

- 9.

It is recommended, that treatment with anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies should be considered for patients with AxSpA and severe recurrent anterior uveitis or chronic uveitis refractory to conventional therapy (GR: D; LE: 5; GA: 100%).

It is not part of the aim of this document to give recommendations on the ophthalmological treatment of SpA-associated uveitis, but we should mention that, given the efficacy shown in this situation by the various biological therapies, they should be considered with the agreement of the ophthalmologist for patients with acute anterior uveitis refractory to conventional therapy, or severe recurrent uveitis refractory to conventional therapy (very recurrent with more than 3 flares per year or the presence of ocular sequelae compromising vision).

The data published and reported from studies and registries suggest that therapy with anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies reduces the number of new episodes of uveitis in patients with AxSpA better than treatment with etanercept.132–135 However, there is no evidence that etanercept increases the number of episodes of uveitis in these patients. Moreover, in a controlled study comparing etanercept with sulfasalazine, the drug that is usually used to reduce uveitis flares in patients with AxSpA, no significant differences were found in the rate of onset of uveitis between either treatment.136

There is insufficient evidence for the efficacy of the new anti-IL-12/23 or anti-IL-17 therapies in treating SpA-associated uveitis. However, the data from the different clinical trials of secukinumab do not show that its administration is associated with an increased incidence of uveitis flares in these patients.26

- 10.

It is recommended that treatment with anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies should be considered for patients with AxSpA and active inflammatory bowel disease or a history of inflammatory bowel disease (GR: D; NE: 5; GA: 100%).

Neither is it part of the objective of this document to give recommendations on the specific treatment of inflammatory bowel disease-associated SpA, but it should be mentioned that, given the efficacy shown in this situation by the anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies, they should be considered, in agreement with the gastroenterologist, for these patients, in an attempt to coordinate the management of the disease's different domains: articular and digestive. The biological drugs currently indicated in Spain for Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis are infliximab, adalimumab and vedolizumab (humanised monoclonal antibody IgG1 that binds to α4β7 integrin). The latter is not effective for joint involvement; therefore, its use is restricted to intestinal activity. Golimumab is indicated for ulcerative colitis but not for Crohn's disease. Certolizumab has not been licensed by the EMA for any inflammatory bowel disease, but it has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of Crohn's disease.

The soluble receptor, etanercept, is not indicated with inflammatory bowel disease, and there are no data that show efficacy in this situation. However, neither are there any data to show that its use aggravates or increases the number of episodes of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with AS.137

Ustekinumab has recently been licensed by the FDA for treatment of Crohn's disease refractory to anti-TNF drugs, based on the published evidence.138 Although there is preliminary data on the efficacy of ustekinumab for patients with AS,30 there is no definitive data available yet and, therefore, it has no approved indication for patients with AxSpA.

There is no data to support the efficacy of secukinumab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's and ulcerative colitis) associated with AxSpA. In a study on patients with active moderate/severe Crohn's disease, treatment with secukinumab showed no efficacy, and had a higher adverse event rate than the placebo.29 However, from the data published in the registry studies with secukinumab for AS, and their extensions, the drug has not been shown to increase the number of episodes of inflammatory bowel disease in these patients.139

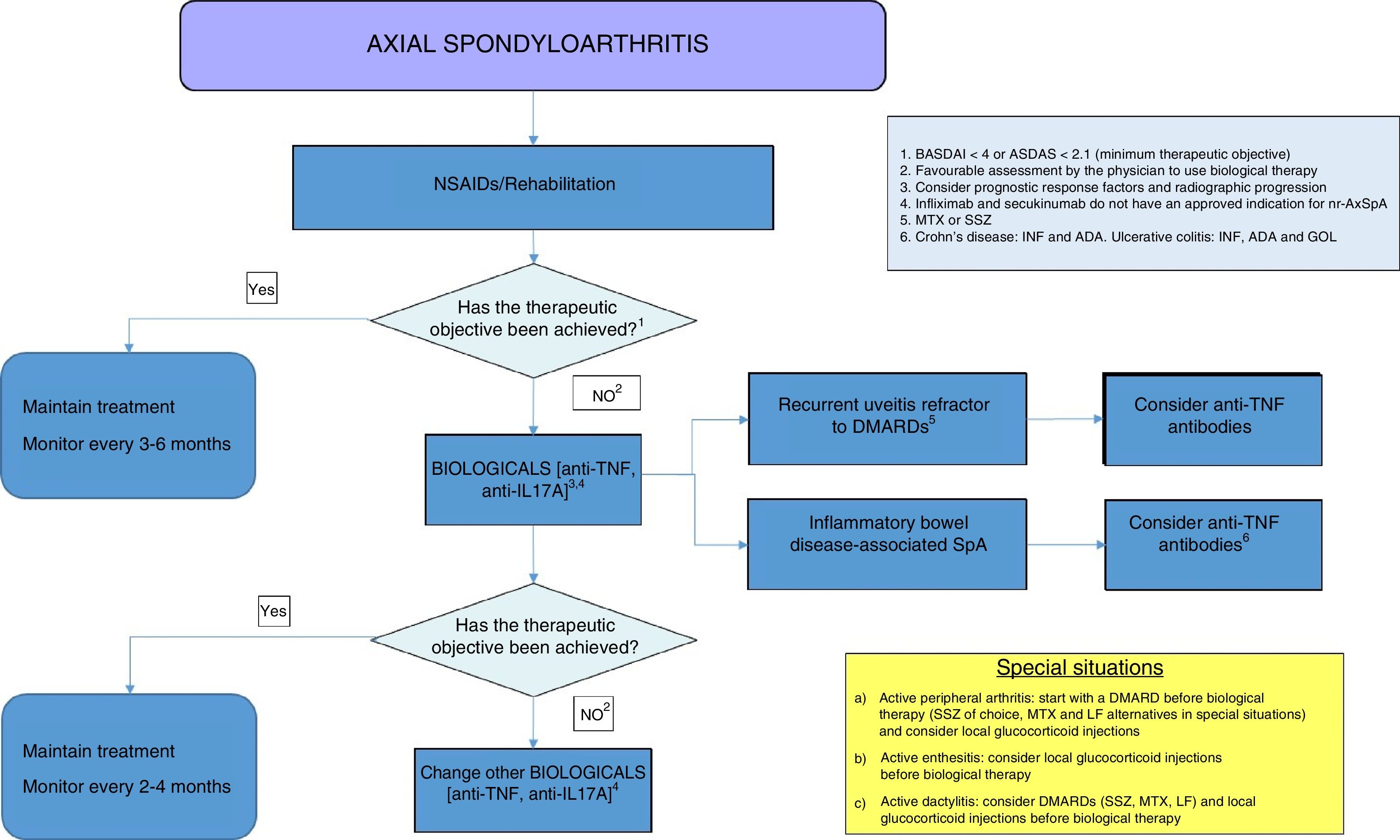

DiscussionThis document forms part of the third update of the SER Consensus on the use of BT for AxSpA. The document is supported in the revisions and recommendations of the recent update of ESPOGUÍA3 and in a critical revision of the previous consensus,14 and is based on the best available scientific evidence and expert clinical experience. There is a change of structure from the previous consensus, based on drawing up a series of scientific evidence-based recommendations and shown in a table. Some of the recommendations included additional clarifications, with relevant information that we as panel members believed it necessary to highlight. Finally, the text also includes a treatment algorithm based on the recommendations made (Fig. 1). We sincerely believe that this format will facilitate decision-making by our colleagues for patients with AxSpA who require BT.

Treatment algorithm for axial spondyloarthritis. ADA: adalimumab; NSAIDS: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; anti-IL17: interleukin 17 inhibitor; anti-TNF: tumour necrosis factor inhibitor; ASDAS: ASAS-endorsed disease activity score; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; DMARDs: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; GOL: golimumab; INF: infliximab; LF: leflunomide; MTX: methotrexate; SSZ: sulfasalazine.

We wanted to explicitly highlight in these recommendations, from the introduction, the unit that is comprised by AxSpA in the judgement of the panel members. We consider it to be a group of processes with similar clinical features and disease load and which, therefore, with subtle differences in their indication, could all be candidates for BT.

The section on new available biological drugs includes certolizumab pegol, a new anti-TNF, with a level of evidence in the treatment of AxSpA similar to that of the other available anti-TNF drugs. We have also included the concept of biosimilars, and their indications. We currently have 3 infliximab biosimilars and one etanercept biosimilar available to us. Finally, possibly the most novel drug secukinumab is included in the section on drugs (IL-17A inhibitor), the first molecule with a different therapeutic target to that of TF. The inclusion of secukinumab is not only relevant because it broadens the spectrum of possible therapeutic targets, but because it constitutes the culmination of an entire series of discoveries made over the past decade concerning the intestinal mucous membrane barrier and the IL-23/IL-17 axis that have enabled a better understanding of the pathophysiology of SpA.140

Another contribution included in the document, without completely abandoning the BASDAI, is the preferential inclusion of the ASDAS score to evaluate disease activity, and to establish therapeutic objectives. This decision is backed by the firm commitment on the part of the panel members to treat-to-target (T2T) strategies, with strict monitoring of the disease, a situation where the ASDAS has proven clearly superior to the BASDAI in predicting patient outcomes.45

In the section on patients with AS refractory to conventional therapy, we decided to place the anti-TNF drugs and secukinumab at the same level. This decision, also reflected in the therapeutic algorithm, is somewhat different to other recently published international recommendations,2 but is based, in our judgement, on the absence of differences between the different molecules, from the results of the registry trials.12,13,26 The panel members are, however, aware that there is much more efficacy and safety data available for the anti-TNF drugs that originate from clinical trials and from routine clinical practice over more than two decades, which places these drugs in a pre-eminent position in the treatment of these patients.

The new data published in the literature have enabled us to included new recommendations on predictive factors of response and structural damage progression which should facilitate decision-making in certain circumstances. We have also added recommendations for the treatment of patients who are refractory to anti-TNF (of special interest on this occasion since a molecule directed at a therapeutic target other than TNF is now available to us for the first time). And finally, we include recommendations for optimising BT in patients who have reached and maintained the therapeutic target for some time. The scientific evidence for the latter remains poor, but they have been endorsed through clinical practice.

We make these recommendations based on scientific evidence and have deliberately not included any reference to other pharmacoeconomic drugs. The members of the panel consider that these aspects change over time and differ throughout the country's different regions and hospitals and are therefore a matter for each rheumatologist to consider based on their own specific conditions. However, in a situation of identical efficacy and safety, cost must be borne in mind in decision-sharing between patients and physicians as to the BT that should be prescribed. Finally, we have also included recommendations for the management of patients with AxSpA and peripheral arthritis, because, although they do not fall within the objective of these recommendations, they might be useful to our colleagues, and have not been included in any other consensus.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingFundación Española de Reumatología (Spanish Rheumatology Foundation)

Conflict of InterestsJordi Gratacós Masmitjà has received funding from UCB, MSD, Pfizer, Abbvie, Janssen, Celgene and Novartis for attending courses/conferences and as a speaker; funding from Abbvie, MSD and Pfizer for undertaking educational programmes and courses and for taking part in a research study, and has received grants from Pfizer, Abbvie, Janssen, Celgene and Novartis as a consultant for pharmaceutical companies and other technologies.

Cristina Fernández Carballido has received funding from Abbvie, Pfizer, MSD, Celgene and Novartis for attending courses/conferences; speaker honoraria from Abbvie, UCB, Celgene and Novartis; funding from Abbvie and MSD for undertaking educational programmes and courses; funding from Novartis for taking part in a research study, and has received grants from Abbvie, Celgene and Novartis as a consultant for pharmaceutical companies and other technologies.

Xavier Juanola Roura has received funding from Abbvie, Pfizer and MSD for attending courses/conferences; speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Pfizer, UCB and MSD; funding from Abbvie for taking part in a research study, and has received grants from Celgene, Novartis and Abbvie as a consultant for pharmaceutical companies and other technologies.

Luis Francisco Linares Ferrando has received funding from Abbvie, Pfizer, Novartis and MSD for attending courses/conferences; speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Pfizer, Grunenthal, Jansen and MSD; funding from the Medical College of Murcia for undertaking educational programmes and courses; funding from Abbvie and Novartis for taking part in a research study and has received a grant from MSD as a consultant for pharmaceutical companies and other technologies.

Eugenio de Miguel Mendieta has received funding from Abbvie, Pfizer, Roche and MSD for attending courses/conferences; speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Janssen, Roche, UCB, Menarini, Celgene and MSD; funding from Abbvie and MSD for undertaking educational programmes and courses; funding from Pfizer for taking part in a research study, and has received grants from Abbvie and Astra-Zeneca as a consultant for pharmaceutical companies and other technologies.

Santiago Muñoz Fernández has received funding from Abbvie, Pfizer, Bioibérica, UCB, Actelion, Roche, Lilly and MSD for attending courses/conferences; speaker honoraria from Janssen, Novartis, UCB, MSD, Abbvie and Pfizer; funding from UCB, Abbvie, Janssen, MSD, Celgene, Sanofi and Roche for undertaking educational programmes and courses, and has received grants from BMS, Abbvie, Novartis, Janssen, Pfizer, Sanofi and Roche as a consultant for pharmaceutical companies and other technologies.

Victoria Navarro Compán has received funding from Abbvie, Bristol, MSD, Pfizer and UCB for attending courses/conferences; speaker and consultant honoraria from Abbvie, BMS, Novartis and Roche, and funding from Abbvie for research projects.

Jose Luis Rosales Alexander has received funding from Pfizer, Roche, BMS, Novartis, Celgene and UCB for attending courses/conferences; honoraria from UCB for attending a round table and as a consultant; funding from FAES for undertaking educational programmes and courses and has received a grant from Grunenthal as a consultant.

Pedro Zarco Montejo has received funding from Abbvie, Pfizer and MSD for attending courses/conferences; speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Pfizer, UCB and MSD, and from Pfizer and UCB as a consultant for pharmaceutical companies and other technologies.

The group of experts who drew up this paper would like to thank the rheumatologists who took part in the evidence review phase: Miguel Ángel Abad Hernández, Gloria Candelas Rodríguez, María Betina Nishishniya Aquino, Claudia Pereda Testa and Ana Ortiz García. We would also like to thank Dr. Federico Díaz González, Director of the SER Research Unit, for his participation in reviewing the final manuscript and for helping to preserve the confidentiality of this document, and Daniel Seoane, a methodologist from SER, for his collaboration in this paper.

Please cite this article as: Gratacós J, Díaz del Campo Fontecha P, Fernández-Carballido C, Juanola Roura X, Linares Ferrando LF, de Miguel Mendieta E, et al. Recomendaciones de la Sociedad Española de Reumatología sobre el uso de terapias biológicas en espondiloartritis axial. Reumatol Clin. 2018;14:320–333.