Describe the demographic characteristics and disorders of patients with diagnosis of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) in the December 2008–January 2014 period.

MethodsMedical records were reviewed from diagnosis of MAS and after discharge until January 2014. Patients were divided into 4 groups according to the primary disease: autoimmune (AI), hemato-oncologic (HO), infectious (Inf) and oncologic (Onc). The variables were analyzed among the 4 groups and between AI and HO.

ResultsThirteen patients [7 men, with a median of 54 years (32–63)] were studied. The etiologies were: 5 AI, 5 HO, 2 Inf and 1 Onc disease. Hemophagocytic cells were found in the ascitic fluid of one patient. A patient with MAS secondary to IgG4-related disease was found.

ConclusionsMortality, prognosis and disease progression may be influenced by the delay in diagnosis, treatment initiation and etiology of MAS. HO ill patients had a worse prognosis.

Describir las características demográficas y trastornos de pacientes con diagnóstico de síndrome de activación macrofágica (SAM) en el periodo comprendido entre diciembre de 2008-enero de 2014.

MétodosSe revisaron las historias clínicas desde el diagnóstico de SAM y tras su alta hospitalaria hasta enero de 2014. Los pacientes se agruparon en 4 grupos: autoinmunes (AI), hemato-oncólogicas (HO), infecciosas (Inf) y oncológicas (Onc). Las variables fueron analizadas entre los 4 grupos y entre AI y HO.

ResultadosTrece pacientes (7 hombres, con una mediana de 54 años [32-63]) se estudiaron. Las etiologías encontradas fueron: 5 AI, 5 HO, 2 Inf y una Onc. Se encontraron células hemofagocíticas en el líquido ascítico en uno de los pacientes. Se encontró un paciente con SAM secundario a enfermedad relacionada con la IgG4.

ConclusionesLa mortalidad, el pronóstico y la evolución de la enfermedad puede verse influida por el retraso en el diagnóstico, el inicio del tratamiento y la etiología del SAM. Los pacientes con enfermedades HO presentaron peor pronóstico.

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is a group of diseases characterized by a severe acute inflammatory syndrome, usually underdiagnosed.1 The usual clinical manifestations are fever, rash, enlarged organs and central nervous system alterations. Laboratory analysis usually shows pancytopenia, hepatitis, coagulopathy, hyperferritinemia and hypertriglyceridemia, and histologically the presence of hemophagocytic cells (HC) on bone marrow (BM), spleen and/or lymph node biopsy.1,2

This disease is caused by proliferation and activation of T cells and macrophages, causing an inflammatory response characterized by hypersecretion of cytokines such as interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-18, and macrophage colony stimulating factor.1,2 Secondary MAS is the result of an immunological reaction caused by autoimmune disease, infection, exposure to drugs and neoplasms.2,3MAS secondary to autoimmune diseases (AD) has certain differences from the other types such as very high hyperferritinemia, a decrease in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, a mild cytopenia and a more pronounced initial3 coagulopathy. It can occur at any age, but especially at the beginning of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and adult Still's disease (ASD), and during the development of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It is estimated to occur in 7% of the patients with JIA, with a mortality rate ranging between 10 and 20%.2–4

In recent years we have witnessed an increased incidence of this disease, probably because before it was underdiagnosed due to lack of knowledge regarding it. It is for this reason that we decided to conduct a review of the cases to date in our hospital.

ObjectiveTo describe the demographic, clinical and laboratory data, treatment strategies, mortality and underlying disorders during hospitalization and after discharge of patients diagnosed with MAS during the period of December 2008–January 2014 in the Hospital Universitario Donostia, Gipuzkoa, Spain.

Materials and MethodsIn order to describe the clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with MAS we reviewed paper and computerized medical records. Following data collection patients were grouped into 4 groups according to the underlying disease: AD, hemato-oncologic (HO), infectious (Inf) and oncologic (Onc).

Nominal variables were diagnosis, possible triggers of MAS and treatments used during admission and currently. Dichotomous variables were gender, fever, organomegaly, hospital mortality after discharge, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and recurrence of MAS. Quantitative variables were age, analytical findings, hospital stay in days, days from admission to BM biopsy, days after the BM biopsy until discharge or death of the patient and the evolution time after discharge hospital in months. Quantitative variables with a skewed distribution are represented as median and interquartile range.

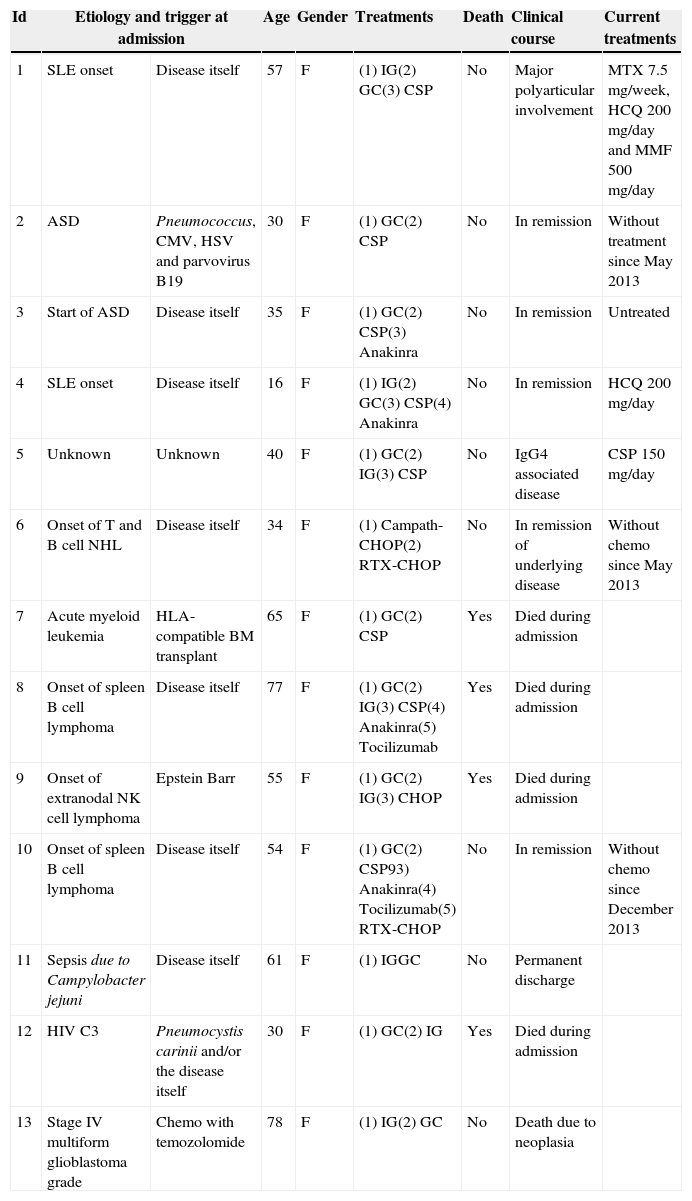

Results13 patients were found 5 with AD, 5 with HO diseases 2, with Inf diseases and one with Onc disease. Table 1 shows demographic characteristics, etiology, possible triggers of MAS, mortality, treatments used during admission and currently as well as clinical outcomes after hospital discharge.

Demographic Characteristics, Etiologies, Triggers, Clinical Course, Treatment and Mortality of Patients With Secondary Macrophage Activation Syndrome.

| Id | Etiology and trigger at admission | Age | Gender | Treatments | Death | Clinical course | Current treatments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SLE onset | Disease itself | 57 | F | (1) IG(2) GC(3) CSP | No | Major polyarticular involvement | MTX 7.5mg/week, HCQ200mg/day and MMF500mg/day |

| 2 | ASD | Pneumococcus, CMV, HSV and parvovirus B19 | 30 | F | (1) GC(2) CSP | No | In remission | Without treatment since May 2013 |

| 3 | Start of ASD | Disease itself | 35 | F | (1) GC(2) CSP(3) Anakinra | No | In remission | Untreated |

| 4 | SLE onset | Disease itself | 16 | F | (1) IG(2) GC(3) CSP(4) Anakinra | No | In remission | HCQ 200mg/day |

| 5 | Unknown | Unknown | 40 | F | (1) GC(2) IG(3) CSP | No | IgG4 associated disease | CSP150mg/day |

| 6 | Onset of T and B cell NHL | Disease itself | 34 | F | (1) Campath-CHOP(2) RTX-CHOP | No | In remission of underlying disease | Without chemo since May 2013 |

| 7 | Acute myeloid leukemia | HLA-compatible BM transplant | 65 | F | (1) GC(2) CSP | Yes | Died during admission | |

| 8 | Onset of spleen B cell lymphoma | Disease itself | 77 | F | (1) GC(2) IG(3) CSP(4) Anakinra(5) Tocilizumab | Yes | Died during admission | |

| 9 | Onset of extranodal NK cell lymphoma | Epstein Barr | 55 | F | (1) GC(2) IG(3) CHOP | Yes | Died during admission | |

| 10 | Onset of spleen B cell lymphoma | Disease itself | 54 | F | (1) GC(2) CSP93) Anakinra(4) Tocilizumab(5) RTX-CHOP | No | In remission | Without chemo since December 2013 |

| 11 | Sepsis due to Campylobacter jejuni | Disease itself | 61 | F | (1) IGGC | No | Permanent discharge | |

| 12 | HIV C3 | Pneumocystis carinii and/or the disease itself | 30 | F | (1) GC(2) IG | Yes | Died during admission | |

| 13 | Stage IV multiform glioblastoma grade | Chemo with temozolomide | 78 | F | (1) IG(2) GC | No | Death due to neoplasia | |

CHOP, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin and prednisone; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CSP, cyclosporin; ASD, Adult Still's disease; F, female; GC, glucocorticoids; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; HSV, herpes simplex virus; Id, identification; IG, immunoglobulin SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; NHL, non Hodgkins lymphoma; M, male; MMF, mycophenolate; MTX, methotrexate; NK, natural killer; Chemo, chemotherapy; RTX, rituximab; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

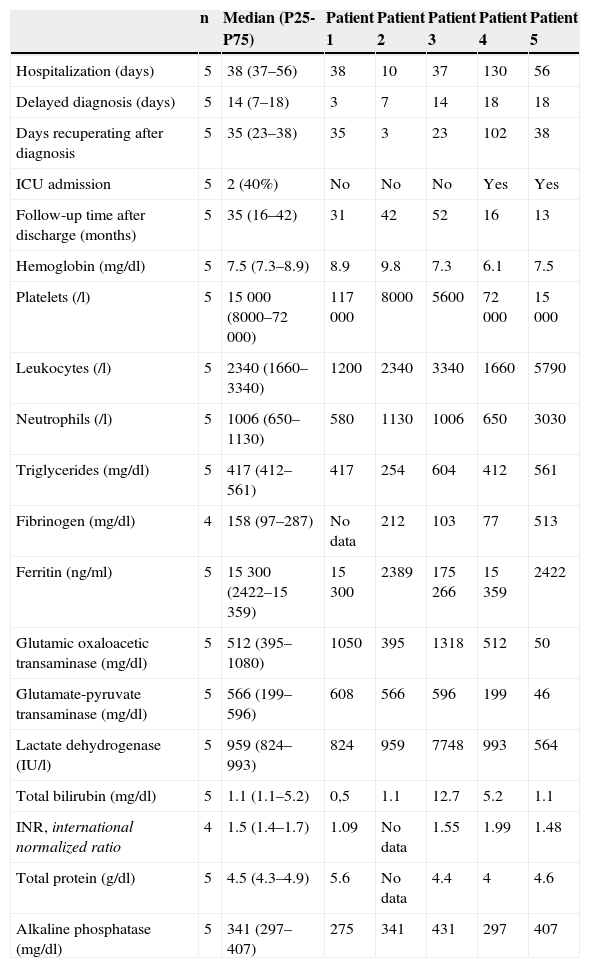

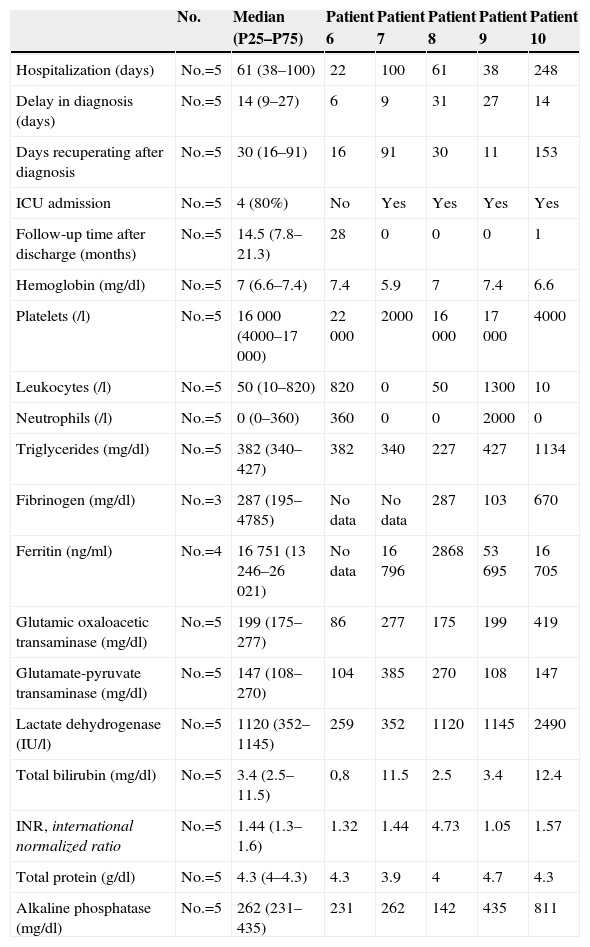

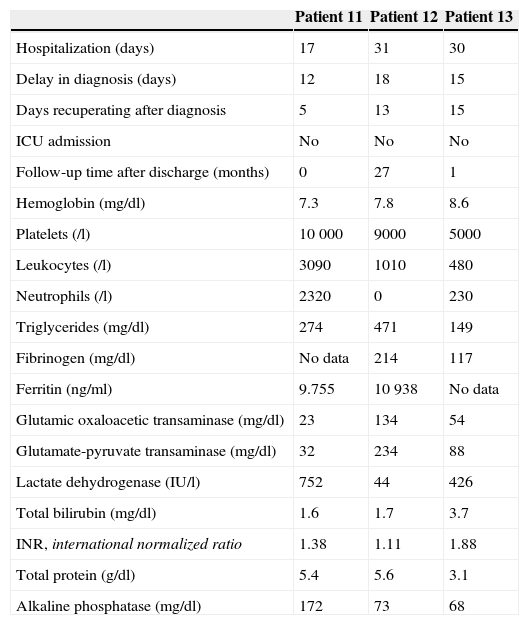

Fever was the only common criterion. Organomegaly (splenomegaly and/or hepatomegaly) was present in all patients except for patient 13. Tables 2–4 show the descriptive analysis of patients with secondary MAS shown by type of disease. Patients 6, 7 and 8 underwent more than one BM biopsy and patient 3 also presented HC and ascites.

Descriptive Analysis of the Variables of Patients With Macrophage Activation Syndrome Secondary to Autoimmune Diseases.

| n | Median (P25-P75) | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization (days) | 5 | 38 (37–56) | 38 | 10 | 37 | 130 | 56 |

| Delayed diagnosis (days) | 5 | 14 (7–18) | 3 | 7 | 14 | 18 | 18 |

| Days recuperating after diagnosis | 5 | 35 (23–38) | 35 | 3 | 23 | 102 | 38 |

| ICU admission | 5 | 2 (40%) | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Follow-up time after discharge (months) | 5 | 35 (16–42) | 31 | 42 | 52 | 16 | 13 |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dl) | 5 | 7.5 (7.3–8.9) | 8.9 | 9.8 | 7.3 | 6.1 | 7.5 |

| Platelets (/l) | 5 | 15 000 (8000–72 000) | 117 000 | 8000 | 5600 | 72 000 | 15 000 |

| Leukocytes (/l) | 5 | 2340 (1660–3340) | 1200 | 2340 | 3340 | 1660 | 5790 |

| Neutrophils (/l) | 5 | 1006 (650–1130) | 580 | 1130 | 1006 | 650 | 3030 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 5 | 417 (412–561) | 417 | 254 | 604 | 412 | 561 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 4 | 158 (97–287) | No data | 212 | 103 | 77 | 513 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 5 | 15 300 (2422–15 359) | 15 300 | 2389 | 175 266 | 15 359 | 2422 |

| Glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (mg/dl) | 5 | 512 (395–1080) | 1050 | 395 | 1318 | 512 | 50 |

| Glutamate-pyruvate transaminase (mg/dl) | 5 | 566 (199–596) | 608 | 566 | 596 | 199 | 46 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (IU/l) | 5 | 959 (824–993) | 824 | 959 | 7748 | 993 | 564 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 5 | 1.1 (1.1–5.2) | 0,5 | 1.1 | 12.7 | 5.2 | 1.1 |

| INR, international normalized ratio | 4 | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | 1.09 | No data | 1.55 | 1.99 | 1.48 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 5 | 4.5 (4.3–4.9) | 5.6 | No data | 4.4 | 4 | 4.6 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (mg/dl) | 5 | 341 (297–407) | 275 | 341 | 431 | 297 | 407 |

Descriptive Analysis of the Variables of Patients With Macrophage Activation Syndrome Secondary to Hemato-oncological Diseases.

| No. | Median (P25–P75) | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | Patient 9 | Patient 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization (days) | No.=5 | 61 (38–100) | 22 | 100 | 61 | 38 | 248 |

| Delay in diagnosis (days) | No.=5 | 14 (9–27) | 6 | 9 | 31 | 27 | 14 |

| Days recuperating after diagnosis | No.=5 | 30 (16–91) | 16 | 91 | 30 | 11 | 153 |

| ICU admission | No.=5 | 4 (80%) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Follow-up time after discharge (months) | No.=5 | 14.5 (7.8–21.3) | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dl) | No.=5 | 7 (6.6–7.4) | 7.4 | 5.9 | 7 | 7.4 | 6.6 |

| Platelets (/l) | No.=5 | 16 000 (4000–17 000) | 22 000 | 2000 | 16 000 | 17 000 | 4000 |

| Leukocytes (/l) | No.=5 | 50 (10–820) | 820 | 0 | 50 | 1300 | 10 |

| Neutrophils (/l) | No.=5 | 0 (0–360) | 360 | 0 | 0 | 2000 | 0 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | No.=5 | 382 (340–427) | 382 | 340 | 227 | 427 | 1134 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | No.=3 | 287 (195–4785) | No data | No data | 287 | 103 | 670 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | No.=4 | 16 751 (13 246–26 021) | No data | 16 796 | 2868 | 53 695 | 16 705 |

| Glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (mg/dl) | No.=5 | 199 (175–277) | 86 | 277 | 175 | 199 | 419 |

| Glutamate-pyruvate transaminase (mg/dl) | No.=5 | 147 (108–270) | 104 | 385 | 270 | 108 | 147 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (IU/l) | No.=5 | 1120 (352–1145) | 259 | 352 | 1120 | 1145 | 2490 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | No.=5 | 3.4 (2.5–11.5) | 0,8 | 11.5 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 12.4 |

| INR, international normalized ratio | No.=5 | 1.44 (1.3–1.6) | 1.32 | 1.44 | 4.73 | 1.05 | 1.57 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | No.=5 | 4.3 (4–4.3) | 4.3 | 3.9 | 4 | 4.7 | 4.3 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (mg/dl) | No.=5 | 262 (231–435) | 231 | 262 | 142 | 435 | 811 |

Descriptive Analysis of the Variables of Patients With Macrophage Activation Syndrome Secondary to Infectious and Oncological Diseases.

| Patient 11 | Patient 12 | Patient 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization (days) | 17 | 31 | 30 |

| Delay in diagnosis (days) | 12 | 18 | 15 |

| Days recuperating after diagnosis | 5 | 13 | 15 |

| ICU admission | No | No | No |

| Follow-up time after discharge (months) | 0 | 27 | 1 |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dl) | 7.3 | 7.8 | 8.6 |

| Platelets (/l) | 10 000 | 9000 | 5000 |

| Leukocytes (/l) | 3090 | 1010 | 480 |

| Neutrophils (/l) | 2320 | 0 | 230 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 274 | 471 | 149 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | No data | 214 | 117 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 9.755 | 10 938 | No data |

| Glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (mg/dl) | 23 | 134 | 54 |

| Glutamate-pyruvate transaminase (mg/dl) | 32 | 234 | 88 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (IU/l) | 752 | 44 | 426 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.6 | 1.7 | 3.7 |

| INR, international normalized ratio | 1.38 | 1.11 | 1.88 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 5.4 | 5.6 | 3.1 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (mg/dl) | 172 | 73 | 68 |

With regard to treatment strategies, all patients received glucocorticoids (GC), 8 patients (3 AD and 2 HO, 2 Inf and 1 Onc) received immunoglobulin (IG), 8 patients (5 AD and 3 HO) received cyclosporine (CSP), 4 patients (2 AD and 2 HO) received anakinra, 2 patients (2 HO) tocilizumab and chemotherapy. All patients received broad spectrum antibiotics, except patient 11. Most patients received maintenance therapy and transfusions of red blood cells and platelets, colony stimulating factor, erythropoietin and vasopressors. Patient 5 required three hemodialysis sessions during hospitalization due to fluid overload, and clinicians, during admission, did not reach a definite etiologic diagnosis but seven months after discharge identified it as an IgG4-related disease.

Patients 7, 8 and 9 died during admission with a diagnosis of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) and patient 12 presented massive hemoptysis; 13 patients died after discharge due to their underlying disease. Five patients were admitted to the ICU, all for MODS. Patients 4 and 7 had 2 admissions to the ICU each, with the second admission diagnosis being, in patient 7, MODS and sepsis as well as bacterial peritonitis in patient 4 due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecallis and Bacteroides fragillis, requiring up to 4 surgical cavity lavages. No patient had a recurrence of MAS after discharge.

DiscussionThe main diseases related to MAS in our study were AD and HO, these being the most frequent. With respect to AD, we found 3 patients who started with MAS and one that presented the ethological diagnosis after hospital discharge, which was associated with IgG4 disease, the first case reported of this association with MAS.

In a series of 18 patients in the US, one case was found after bone marrow transplantation.4,5 In a series of 58 patients with HIV in France, other infectious agents were described, including HIV, acting as triggers of MAS.6MAS cases secondary to Pneumocystis jirovecii have been reported in patients with HO disease and not in HIV.9 Patient 12 could be the first case of MAS secondary to P. jirovecii in a patient with HIV, although HIV could also be the cause of MAS.

The most common bacteria related to MAS are Salmonella, Tuberculosis and Pseudomonas,5 and within the Enterobacteriaceae isolated cases of Serratia, Klebsiella and Campylobacter have been reported.7–9 In 2001, the first described case of MAS secondary to Campylobacter fetus was reported in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Patient 11 is the first case of MAS secondary to Campylobacter jejuni.

Regarding MAS secondary to chemotherapy, cases have been rarely described. In 2012 a patient with neuroblastoma was associated to MAS after starting chemotherapy.10 Patient 13 is probably the first case of MAS secondary to chemotherapy with temozolomide, although MAS could also be attributed to the tumor itself, albeit less likely.

None of the patients underwent quantification of natural killer cells and sIL-2 receptor because these tests are not performed in our hospital. These tests are not available in all hospitals, and when performed, the results are often slow to come. It is for this and the high mortality related to MAS that these tests should not be decisive for the diagnosis, let alone onset of treatment, provided there is a high suspicion of MAS.1,10,11

In patient 3, HC were found in ascites. There are some reports in the literature of HC in pathological body fluids. The first case of HC in ascites was described in 2007 in a patient with liver cirrhosis and Escherichia coli, with another in 2008 in a patient after a cholecystectomy.12,13 In the pleural fluid 2 cases induced by EBV have been described.14,15 In 2007, the first case of HC in the cerebrospinal fluid in a patient with visceral leishmaniasis was described.16 This could lead us to the conclusion that HC could be found in any pathological body fluid before undertaking a BM biopsy, or when faced with inconclusive biopsies; this is another element to consider for the diagnosis.

A relationship was noted between more hospital days from admission to the BM biopsy and the onset of treatment with greater mortality, especially in patients with HO diseases. The main cause of mortality was MODS, although patients were treated with broad spectrum antibiotics, antifungals and antiretroviral drugs. This suggests that mortality is mainly due to MAS and not to a possible associated infection.

The goal of treatment is to stop the inflammatory process. Initial treatments are GC such as methylprednisolone or dexamethasone in children because they easily cross the blood brain barrier. IGs are another option when suspecting a viral infection and in severe cases where no expected response to GC is expected. GC should be reduced slowly and progressively in order to avoid reactivation.1 In refractory cases or reactivation, CSP doses between 2 and 8mg/kg/day could be associated. Biological treatments are used when GC and/or synthetic immunosuppressive drugs have not been effective. Receptor inhibitors of TNF, IL-1 and IL-6 are an option; these should be used with caution and monitoring of side effects or complications such as infections. Rituximab has proven effective in patients with MAS secondary to SLE.3,17 Anakinra is effective in MAS secondary to systemic JIA; it also shows an advantage over other biological treatments, and it is a drug with a short half-life.2 We must also remember that there have been reports of MAS secondary to biological treatment.5

Other measures to consider during immunosuppressive therapy are gastric protection, cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, oral antifungal drugs and evaluating the use of antiretrovirals.1 The onset of antibiotic therapy is controversial and depends on several factors such as comorbidities. In reactivation cases, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be employed, although some authors recommend their use at the start of immunosuppressive treatment.1

The objective of this study was to collect and analyze the experience in our hospital, and thus provide information for future work. We can see that MAS could be suspected in patients with prolonged fever unresponsive to broad-spectrum antibiotics and be accompanied by organomegaly, cytopenias, coagulopathy and hepatitis. The early diagnosis and initiation of treatment may improve the prognosis, and compliance with all diagnostic criteria should not be strictly necessary for initiating treatment, due to the diseases’ high mortality.

ConclusionsMortality, prognosis and disease progression may be influenced by delay in diagnosis, treatment initiation and etiology of MAS. HC may be present not only in the bone marrow, lymph nodes and spleen, but also in other pathological body liquids, such as ascites. The secondary MAS hemato-oncological diseases presented worse prognosis.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this research did not perform experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace regarding the publication of data from patients, and all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors state that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of InterestThe authors have no conflict of interest to state.

Please cite this article as: Egües Dubuc C, Aldasoro Cáceres V, Uriarte Ecenarro M, Errazquin Aguirre N, Hernando Rubio I, Meneses Villalba CF, et al. Síndrome de activación macrofágica secundario a enfermedades autoinmunes, hematológicas, infecciosas y oncológicas. Serie de 13 casos clínicos y una revisión bibliográfica. Reumatol Clin. 2015;11:139–143.