Meralgia paresthetica is a mononeuropathy of the femoral cutaneous nerve with characteristic findings, usually secondary to injury or compression, being most common in the inguinal area. Exceptional cases associated with compressions caused by abdominal or pelvic tumors have been published, so it is always advisable to extend the study with imaging tests. We present a case associated with a renal tumor.

La meralgia parestésica es una mononeuropatía del nervio femorocutáneo con una presentación clínica característica, usualmente secundaria a lesión o atrapamiento en algún punto de su recorrido, siendo más habitual las producidas a nivel inguinal. Sin embargo, se publican casos excepcionales asociados a compresiones originadas por masas ocupantes de espacio a nivel retroperitoneal, por lo que se debería ampliar su estudio con pruebas de imagen ante dicho cuadro clínico. A continuación presentamos un caso asociado a un tumor renal.

Meralgia paresthetica (MP) is a mononeuritis of the femoral cutaneous nerve, a purely sensory nerve, which is characterized by pain and/or paresthesias in the anterolateral thigh and neurological involvement is caused mainly by trauma or compression at some point along its course, ranging from its origin at the root of L2–L3, crossing the lateral border of the psoas muscle (just above the iliac crest), out of the pelvis through the recess formed by the anterior superior and lower iliac notch, passing finally to the thigh1,2 below the inguinal ligament. This neuropathy usually occurs between 30 and 40 years of age, with an incidence of 0.43 per 10000 inhabitants according to some studies, with males being the most affected.3

Depending on its origin, it can be divided into spontaneous or iatrogenic, due to interventions such as orthopedic surgery, laparoscopy, intravascular access via femoral artery, fractures or bone graft extraction; the spontaneous form, in turn, can be divided into idiopathic, metabolic (related to diabetes, lead poisoning, leprosy or hypothyroidism) and/or mechanical, due to some kind of direct compression, internal or external, on the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve somewhere along its route.1 Causes of MP due to spontaneous external mechanical compression include obesity, increased abdominal pressure (such as pregnancy), pressure belts, corsets or tight trousers, secondary causes may be due to the internal compression of a,ass occupying space in the retroperitoneum, pelvic cavity or in the area of the inguinal ligament.4

Here, we present a case of MP with a typical clinical presentation but of an unusual etiology, diagnosed and treated early.

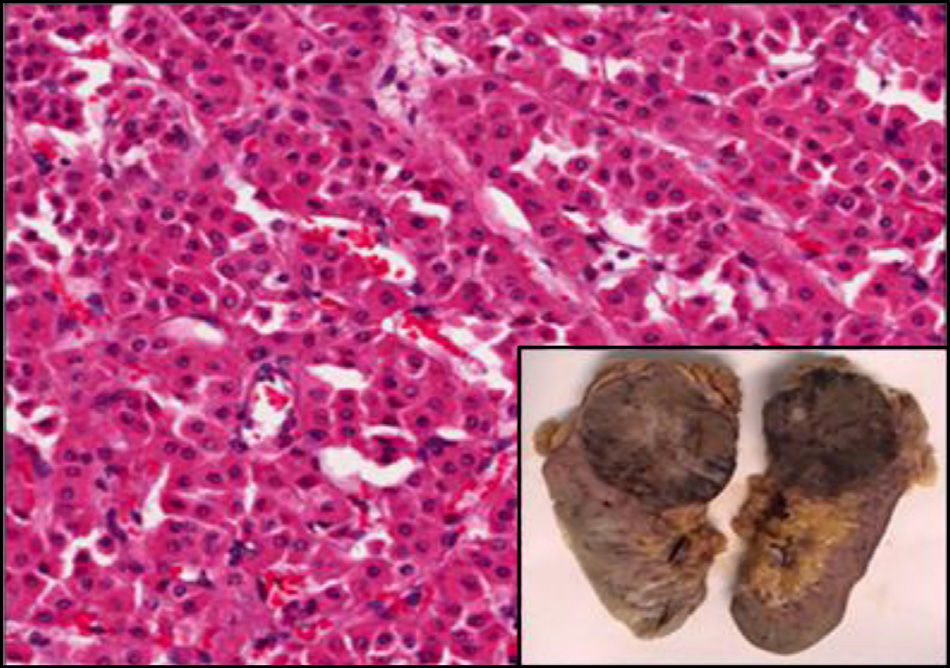

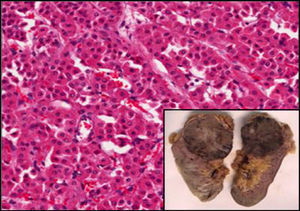

Case PresentationThe case is an obese man of 67 years of age with a history of hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease undergoing treatment and with good clinical stability. He was seen at the rheumatology outpatient clinic due to mechanical low back pain as well as paresthesias of moderate intensity in the anterolateral aspect of the left thigh of 3 months duration, which were exacerbated by prolonged standing and improved with rest, denying any other symptoms. Physical examination highlighted a large abdomen, no pain upon pressure of the spinous processes of the spine, negative root maneuvers and hip exploration within normal, compatible with a MP. Since spine and hip X-rays showed no significant alterations, we requested laboratory tests and an abdominal CT to complete the evaluation. The results of the blood count, biochemistry tests, tumor markers and urinalysis were within normal, but a computed tomography revealed a 79mm mass in the upper pole of the left kidney with a possible necrotic center and a perirenal fat invasion foci at the top corner, suggesting a malignancy, with no other involvement or enlarged lymph nodes (Fig. 1). Then the patient was referred to the urology department, who proceeded to perform a left nephrectomy with a favorable postoperative outcome. Subsequently, the patients back pain and paresthesias disappeared. The specimen was sent to pathology; histological findings showed a robust proliferation of monomorphic cells with little nuclear atypia and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with well defined limits, all compatible with a renal oncocytoma (Fig. 2).

The diagnosis of MP was established by its typical clinical presentation, associated with a characteristic neurological examination; however, it is important for an adequate differential diagnosis to investigate the presence of other associated symptoms, as well as other musculoskeletal, neurological, urogenital or gastrointestinal conditions that might be related to MP.4 Initially, the radiographic study and complete analysis allowed us to rule out the presence of bone tumors or metabolic disorders, respectively; the use of MRI, CT or ultrasound is also indicated in suspected pelvic or retroperitoneal tumors.5,6 Finally, neurophysiological studies using somatosensory evoked potentials, a conduction test and nerve blockage tests with anesthetics and corticosteroids can confirm the diagnosis.7,8

Compression injury of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is favored by its length and its particular anatomical characteristics, the most common are produced in the region of the groin, caused by external compression by the use of belts, tight clothing, a large abdomen2 or by the presence of anatomical abnormalities such as lipomas located at this level.9 Secondary MP due to femoral cutaneous nerve compression caused by intraabdominal retroperitoneal masses, such as hematomas, pseudoaneurysms,10 or soft tissue and bone tumors have been reported.4,11 In this case, after imaging revealed a large renal tumor with pathological features, and faced with a suspicion of malignancy, we decided to perform a left radical nephrectomy, revealing a well-differentiated renal oncocytoma. Subsequently, our patient had a good clinical progression with disappearance of his symptoms. Although renal oncocytoma is a benign neoplasm which constitutes a rare tumor of the kidney (3%–6% of all renal neoplasms), it is clinically and radiologically indistinguishable from renal cell carcinoma, and a definitive diagnosis is only made through histology; oncocytomas are usually asymptomatic (58%–83%), although sometimes they can present with hematuria, back pain or symptoms caused by a retroperitoneal mass effect. Due to all of these uncertainties regarding the preoperative diagnosis, the majority of authors have pointed out the need to treat these tumors aggressively with thermal ablation, partial nephrectomy or radical nephrectomy, according to individual clinical circumstances.12

ConclusionsOur case illustrates a presentation of MP in an obese patient with enough features that could have justified such a neuropathy; however, after studies to rule out other factors that could cause injury and/or entrapment at some point in the course of the femoral cutaneous nerve, we found a left renal tumor with a necrotic center, so faced with a suspicion of malignancy we resorted to radical treatment, with a good outcome.

This case and others mentioned in the literature justify imaging testing such as ultrasound and blood tests in patients with MP, even those with a typical presentation and without any other associated symptoms.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of People and AnimalsThe authors state that no experiments were performed on humans or animals.

Data ConfidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace regarding the publication of data from patients and all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Right to Privacy and Informed ConsentThe authors state that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of InterestThe authors have no disclosures to make.

Please, cite this article as: Ramírez Huaranga MA, et al. Lo que puede esconder una meralgia parestésica: tumor renal como causa infrecuente. Reumatol Clin. 2013;9:319–321.