One of the missions of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology is to provide the necessary tools for excellence in health care. Currently, there is no reference point to quantify medical actions in this specialty, and this is imperative.

Material and methodA list of actions was drawn up and a hierarchical classification system was established by developing a complexity index, calculated based on the completion time and difficulty level of each action.

ResultsThe results of the Delphi method tended to the consensus opinion within a group (mean σ2−σ1=0.75–1.43=−0.68, mean IQR2–IQR1=0.8–1.9=−1.1). The values of the complexity index ranged between 48 and 465 points. Among consultation actions, those reaching the highest scores were the first inpatient visit (366) and visits to the patient's home (369). Among diagnostic techniques, biopsies were prominent, those with the highest score were: bone biopsy (465), sural nerve biopsy (416) and synovial biopsy (380). Ultrasound scan scored 204, capillaroscopy 113 and densitometry 112. Among therapeutic techniques, infiltration/arthrocentesis/articular injection in children reached the highest difficulty (388). The score for ultrasound-guided articular injection was 163. The score for clinical report on disability was 323 and expert report 370.

ConclusionsA nomenclature of 54 actions in Rheumatology was compiled. Biopsies (bone, sural nerve, synovial), inpatient visits, visits to the patient's home, infiltrations in children, and the preparation of the expert report were identified as the most complex actions. Musculoskeletal ultrasound is twice as complex as subsequent visits, capillaroscopy or bone densitometry.

Una misión de la Sociedad Española de Reumatología es aportar las herramientas necesarias para alcanzar la excelencia asistencial. En la actualidad no existe una referencia que cuantifique la complejidad de los actos médicos de esta especialidad.

Material y métodoSe elaboró una relación de los actos propios del reumatólogo y se estableció un sistema de clasificación jerárquica a partir de la construcción de un índice de complejidad, calculado mediante el tiempo de realización y el grado de dificultad de cada acto.

ResultadosLos resultados del método Delphi tendieron a una opinión grupal consensuada (media σ2 - σ1=0,75-1,43=-0,68, media IQR2 - IQR1=0,8-1,9=-1,1). El rango de valores del índice de complejidad osciló de 48 a 465 puntos. Entre las consultas, las que alcanzaron mayor gradación fueron la primera visita al paciente hospitalizado (366) y la visita a domicilio (369). Entre las técnicas diagnósticas, destacaron las biopsias. Las que puntuaron más alto fueron: biopsia ósea (465), de nervio sural (416) y sinovial (380). La ecografía tuvo una puntuación de 204, la capilaroscopia de 113 y la densitometría de 112. Entre las técnicas terapéuticas, la máxima dificultad (388), la alcanzó la infiltración/artrocentesis/inyección articular infantil. La puntuación de la inyección articular con control ecográfico fue de 163. El informe clínico de minusvalía, 323 y el informe pericial, 370.

ConclusionesEste trabajo ha permitido elaborar un nomenclátor de 54 actos en reumatología donde se identifican como actos más complejos la realización de biopsias (ósea, nervio sural, sinovial), la visita a paciente hospitalizado, la visita a domicilio, la infiltración infantil bajo sedación y la elaboración de un informe pericial. La ecografía osteomuscular es considerada el doble de compleja de una visita sucesiva, la capilaroscopia o la densitometría ósea.

Rheumatology is the part of medicine that studies, diagnoses and treats medical diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue.1

The rapid transformation undergone by rheumatology from the syndromes described a century ago (arthritis, arthrosis, gout) to our days has affected not only the pathologies that we can identify, but also the diagnostic techniques that have been developed and the treatments that are used. Rheumatology has clearly evolved more quickly than the resources and criteria which are allocated to our work.

One of the missions of the Sociedad Española de Reumatología (SER) is to supply all of the agents involved in treating rheumatological patients with the instruments that are necessary to improve their quality of life, ensuring they receive the best treatment. To this end it is necessary to create a list of the services that are available in excellent rheumatological care in the 21st century, while also determining their degree of complexity. This list will make it possible to offer the whole range of diagnostic-therapeutic procedures used in rheumatology, together with the standardised degree of complexity of each intervention. It will also be a fundamental instrument for minimising geographical variability in the offer of medical procedures, ensuring that excellent rheumatological care is available throughout Spanish territory.

A list of updated medical interventions agreed by rheumatology professionals and ranked according to their level of complexity would function as a reference to reduce variability in resource availability and improve the quality of care for patients with rheumatic pathology. Although several working criteria currently exist for this purpose, they are obsolete and none of them meets the needs of doctors. The nomenclature of the Organización Médica Colegial does not cover a large part of the work in the speciality of rheumatology2 (Appendix B). On the other hand, the terms applied by insurance companies are very short and incomplete, and they vary widely from province to province.

There is therefore a need to update, broaden and standardise these criteria. In 2006 Olivé et al. prepared a nomenclature for the speciality of Rheumatology with the aim of validating acronyms.3 Although this work covered medical interventions, it did not take their complexity into account. This study has the aim of preparing a nomenclature of medical interventions that is based on a complexity index (CI) which includes the difficulty of the said interventions as well as how long they take to implement. The duration that is desirable in carrying out each medical intervention was stipulated in the work by Alonso et al.4 using the criterion of care quality. This was set in their work using a similar method to ours, that of agreement by a panel of experts using the two-round Delphi process.

The CI was suggested as an approximate measurement of the difficulty of care, with all of the limitations that this involves, as there is no precedent at all in the literature in this field that could be used as a standardised template. Other complex elements such as doctors’ experience or training, the possibility of access to technology or the cost of materials were not included, to prevent increasing variability and arbitrariness.

MethodsGroup of expertsA group of experts was formed to prepare the CI, composed of a head researcher and 30 panellists. The panellists were selected on the basis of their level of knowledge of the subject and degree of collaboration, regardless of their training, their function or the level of their position. The selection criteria were years of experience and representativeness in terms of sex, geographical distribution and public and private care.

Identification and selection of rheumatological interventionsThe first step towards obtaining a nomenclature of medical, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures was to identify rheumatological interventions using the studies published with this purpose3,4 and the opinion of the panel of experts. The study of the definition of each one of them may be consulted in Tables 1–3 of Appendix B (supplementary material available in Internet).

Data gatheringData was gathered using questionnaires sent to the experts, and consensus was achieved using the two-round Delphi method.

QuestionnairesThe questionnaires were sent to the experts by email, so that it was easy for them to answer while ensuring anonymity. Questions were prepared on the degree of difficulty of techniques and their experience in certain processes associated with rheumatological interventions. Experience was defined as their experience in performing the said technique at some time during their clinical practice. The degree of complexity was defined on a scale of from 0 to 10, where 0 was the lowest degree of complexity and 10 the highest.

Data from the first round of questions were analysed to give the general opinion. To this end the average, standard deviation (SD), the median and the interquartile range (IQR) were given for each rheumatological intervention. Once the data from the first round had been collected and analysed, a new questionnaire was designed and sent to the group of experts by email. This second questionnaire asked the experts again for their opinion on the complexity of rheumatological interventions, showing the results of the first round. The aim of this second round was to reduce the scatter of the first round opinions (measured with standard deviation and interquartile range) specifying the agreed average opinion. The experts gave their opinion, justifying it when it diverged strongly from the group view. Analysis of this second round took the same form as it had for the first. When an expert did not answer the second round of questionnaires, they were eliminated from the analysis.

Methodology for the preparation of the complexity indexTo obtain the nomenclature of rheumatological procedures, a hierarchical classification system was created according to their degree of complexity and how long each one takes to perform. A complexity index was calculated as the product of the degree of complication of the procedure and the number of minutes it takes to perform. The degree of difficulty of each rheumatological intervention was obtained using the Delphi process, while the time each rheumatological intervention takes was determined by the findings published by Alonso et al.4

Validation of the complexity indexThe complexity index was validated by a mass survey of the rheumatologists who are members of the SER, asking them about the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with the results obtained. A Likert scale from 1 to 5 was used for this, where 1 was maximum disagreement and 5 was maximum agreement. The quantitative descriptive statistics were summarised to analyse the results (the average and confidence interval, the median and interquartile range) and the frequency of the degree of agreement-disagreement with the results for each intervention.

ResultsA total of 54 interventions were identified and evaluated. 93.3% (28/30) of the panellists took part in the Delphi method.

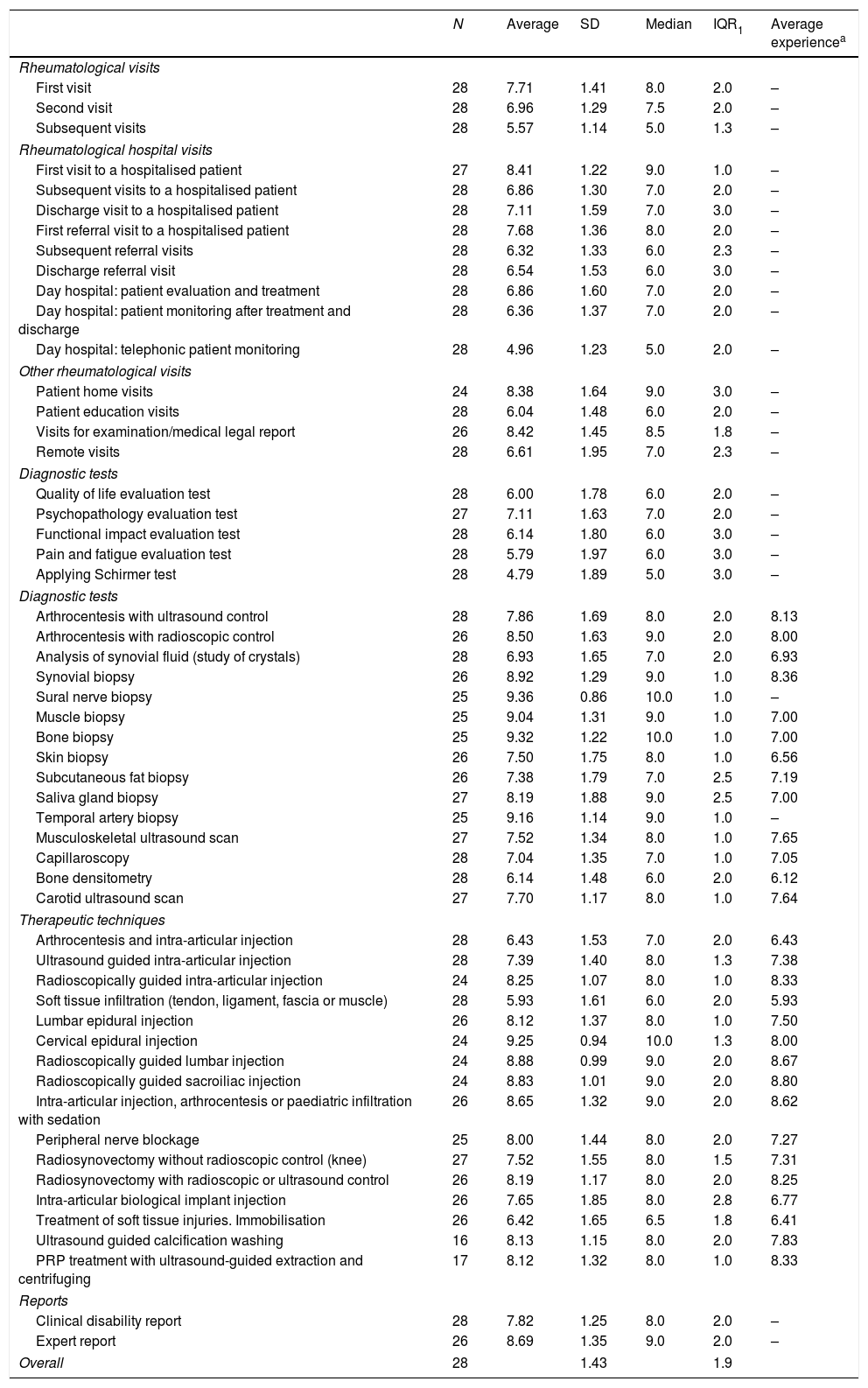

First round DelphiTable 1 shows the results of the first Delphi round. It can be seen that the dispersion of the opinions of the 28 experts amounted to 1.4 points (SD) and 1.9 points (IQR). Only 3 interventions of the 54 had a SD of less than 1 point, and no intervention had an IQR of less than 1 point.

Complexity of medical, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in rheumatology. First round Delphi.

| N | Average | SD | Median | IQR1 | Average experiencea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatological visits | ||||||

| First visit | 28 | 7.71 | 1.41 | 8.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Second visit | 28 | 6.96 | 1.29 | 7.5 | 2.0 | – |

| Subsequent visits | 28 | 5.57 | 1.14 | 5.0 | 1.3 | – |

| Rheumatological hospital visits | ||||||

| First visit to a hospitalised patient | 27 | 8.41 | 1.22 | 9.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Subsequent visits to a hospitalised patient | 28 | 6.86 | 1.30 | 7.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Discharge visit to a hospitalised patient | 28 | 7.11 | 1.59 | 7.0 | 3.0 | – |

| First referral visit to a hospitalised patient | 28 | 7.68 | 1.36 | 8.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Subsequent referral visits | 28 | 6.32 | 1.33 | 6.0 | 2.3 | – |

| Discharge referral visit | 28 | 6.54 | 1.53 | 6.0 | 3.0 | – |

| Day hospital: patient evaluation and treatment | 28 | 6.86 | 1.60 | 7.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Day hospital: patient monitoring after treatment and discharge | 28 | 6.36 | 1.37 | 7.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Day hospital: telephonic patient monitoring | 28 | 4.96 | 1.23 | 5.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Other rheumatological visits | ||||||

| Patient home visits | 24 | 8.38 | 1.64 | 9.0 | 3.0 | – |

| Patient education visits | 28 | 6.04 | 1.48 | 6.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Visits for examination/medical legal report | 26 | 8.42 | 1.45 | 8.5 | 1.8 | – |

| Remote visits | 28 | 6.61 | 1.95 | 7.0 | 2.3 | – |

| Diagnostic tests | ||||||

| Quality of life evaluation test | 28 | 6.00 | 1.78 | 6.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Psychopathology evaluation test | 27 | 7.11 | 1.63 | 7.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Functional impact evaluation test | 28 | 6.14 | 1.80 | 6.0 | 3.0 | – |

| Pain and fatigue evaluation test | 28 | 5.79 | 1.97 | 6.0 | 3.0 | – |

| Applying Schirmer test | 28 | 4.79 | 1.89 | 5.0 | 3.0 | – |

| Diagnostic tests | ||||||

| Arthrocentesis with ultrasound control | 28 | 7.86 | 1.69 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 8.13 |

| Arthrocentesis with radioscopic control | 26 | 8.50 | 1.63 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 8.00 |

| Analysis of synovial fluid (study of crystals) | 28 | 6.93 | 1.65 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 6.93 |

| Synovial biopsy | 26 | 8.92 | 1.29 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 8.36 |

| Sural nerve biopsy | 25 | 9.36 | 0.86 | 10.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Muscle biopsy | 25 | 9.04 | 1.31 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 7.00 |

| Bone biopsy | 25 | 9.32 | 1.22 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 7.00 |

| Skin biopsy | 26 | 7.50 | 1.75 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 6.56 |

| Subcutaneous fat biopsy | 26 | 7.38 | 1.79 | 7.0 | 2.5 | 7.19 |

| Saliva gland biopsy | 27 | 8.19 | 1.88 | 9.0 | 2.5 | 7.00 |

| Temporal artery biopsy | 25 | 9.16 | 1.14 | 9.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Musculoskeletal ultrasound scan | 27 | 7.52 | 1.34 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 7.65 |

| Capillaroscopy | 28 | 7.04 | 1.35 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 7.05 |

| Bone densitometry | 28 | 6.14 | 1.48 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 6.12 |

| Carotid ultrasound scan | 27 | 7.70 | 1.17 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 7.64 |

| Therapeutic techniques | ||||||

| Arthrocentesis and intra-articular injection | 28 | 6.43 | 1.53 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 6.43 |

| Ultrasound guided intra-articular injection | 28 | 7.39 | 1.40 | 8.0 | 1.3 | 7.38 |

| Radioscopically guided intra-articular injection | 24 | 8.25 | 1.07 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 8.33 |

| Soft tissue infiltration (tendon, ligament, fascia or muscle) | 28 | 5.93 | 1.61 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 5.93 |

| Lumbar epidural injection | 26 | 8.12 | 1.37 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 7.50 |

| Cervical epidural injection | 24 | 9.25 | 0.94 | 10.0 | 1.3 | 8.00 |

| Radioscopically guided lumbar injection | 24 | 8.88 | 0.99 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 8.67 |

| Radioscopically guided sacroiliac injection | 24 | 8.83 | 1.01 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 8.80 |

| Intra-articular injection, arthrocentesis or paediatric infiltration with sedation | 26 | 8.65 | 1.32 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 8.62 |

| Peripheral nerve blockage | 25 | 8.00 | 1.44 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 7.27 |

| Radiosynovectomy without radioscopic control (knee) | 27 | 7.52 | 1.55 | 8.0 | 1.5 | 7.31 |

| Radiosynovectomy with radioscopic or ultrasound control | 26 | 8.19 | 1.17 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 8.25 |

| Intra-articular biological implant injection | 26 | 7.65 | 1.85 | 8.0 | 2.8 | 6.77 |

| Treatment of soft tissue injuries. Immobilisation | 26 | 6.42 | 1.65 | 6.5 | 1.8 | 6.41 |

| Ultrasound guided calcification washing | 16 | 8.13 | 1.15 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 7.83 |

| PRP treatment with ultrasound-guided extraction and centrifuging | 17 | 8.12 | 1.32 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 8.33 |

| Reports | ||||||

| Clinical disability report | 28 | 7.82 | 1.25 | 8.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Expert report | 26 | 8.69 | 1.35 | 9.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Overall | 28 | 1.43 | 1.9 | |||

SD: standard deviation; PRP: platelet-rich plasma; IQR: interquartile range [percentile25-percentile75].

These results suggest the need for a new phase to reach a higher level of agreement in expert opinions of the complexity of each intervention.

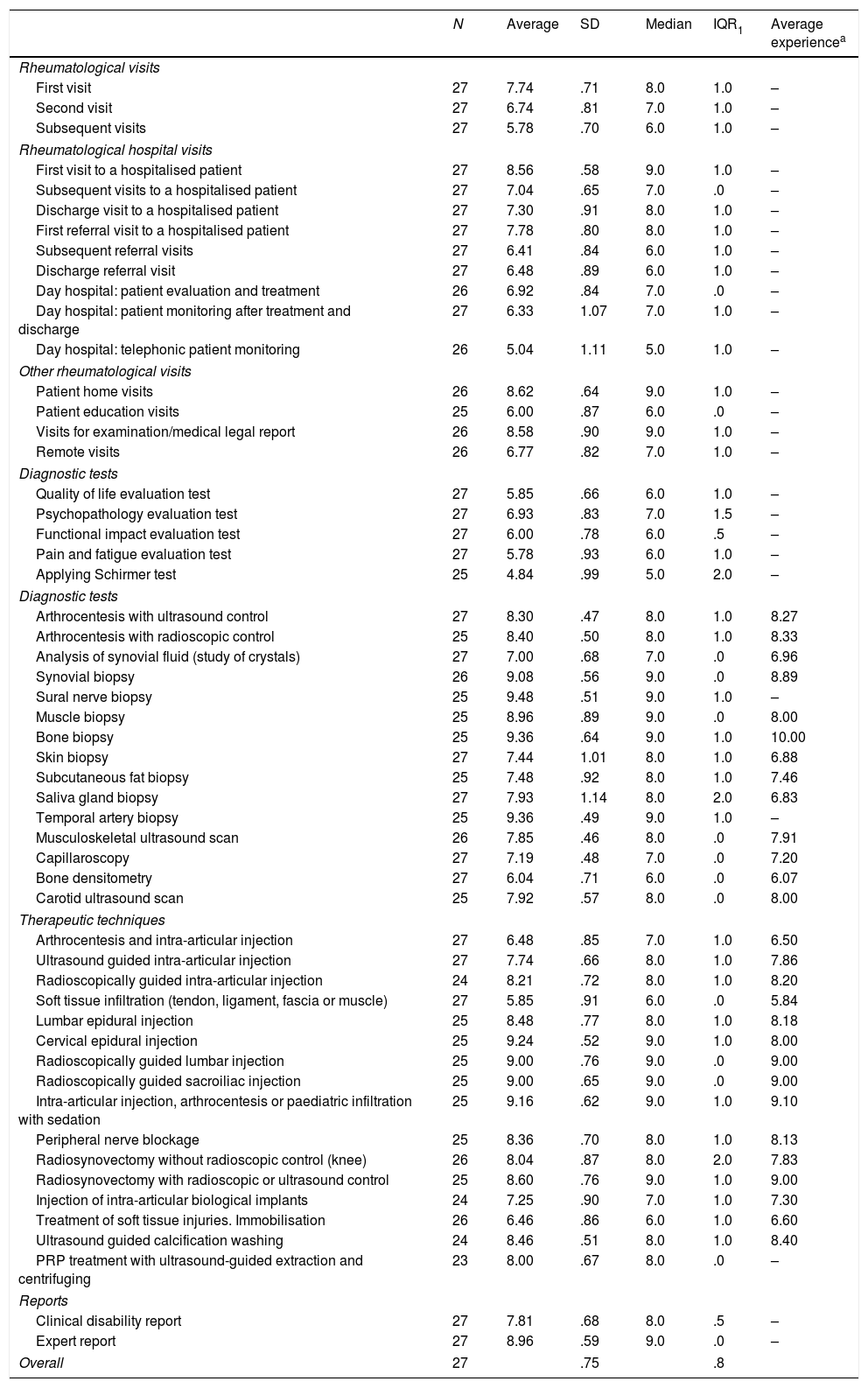

Second round DelphiAfter the second phase of the Delphi method, a higher level of agreement was attained in the overall opinion of the complexity of rheumatological interventions. Thus the SD of opinions was 0.75 points and the IQR was 0.8 points. Only 4 of the 54 interventions had a SD higher than 1 point, while 4 of the 54 interventions had an IQR higher than 1 point. The results of the second round of Delphi are shown in Table 2.

Complexity of medical, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in rheumatology. Second round Delphi.

| N | Average | SD | Median | IQR1 | Average experiencea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatological visits | ||||||

| First visit | 27 | 7.74 | .71 | 8.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Second visit | 27 | 6.74 | .81 | 7.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Subsequent visits | 27 | 5.78 | .70 | 6.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Rheumatological hospital visits | ||||||

| First visit to a hospitalised patient | 27 | 8.56 | .58 | 9.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Subsequent visits to a hospitalised patient | 27 | 7.04 | .65 | 7.0 | .0 | – |

| Discharge visit to a hospitalised patient | 27 | 7.30 | .91 | 8.0 | 1.0 | – |

| First referral visit to a hospitalised patient | 27 | 7.78 | .80 | 8.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Subsequent referral visits | 27 | 6.41 | .84 | 6.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Discharge referral visit | 27 | 6.48 | .89 | 6.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Day hospital: patient evaluation and treatment | 26 | 6.92 | .84 | 7.0 | .0 | – |

| Day hospital: patient monitoring after treatment and discharge | 27 | 6.33 | 1.07 | 7.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Day hospital: telephonic patient monitoring | 26 | 5.04 | 1.11 | 5.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Other rheumatological visits | ||||||

| Patient home visits | 26 | 8.62 | .64 | 9.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Patient education visits | 25 | 6.00 | .87 | 6.0 | .0 | – |

| Visits for examination/medical legal report | 26 | 8.58 | .90 | 9.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Remote visits | 26 | 6.77 | .82 | 7.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Diagnostic tests | ||||||

| Quality of life evaluation test | 27 | 5.85 | .66 | 6.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Psychopathology evaluation test | 27 | 6.93 | .83 | 7.0 | 1.5 | – |

| Functional impact evaluation test | 27 | 6.00 | .78 | 6.0 | .5 | – |

| Pain and fatigue evaluation test | 27 | 5.78 | .93 | 6.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Applying Schirmer test | 25 | 4.84 | .99 | 5.0 | 2.0 | – |

| Diagnostic tests | ||||||

| Arthrocentesis with ultrasound control | 27 | 8.30 | .47 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 8.27 |

| Arthrocentesis with radioscopic control | 25 | 8.40 | .50 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 8.33 |

| Analysis of synovial fluid (study of crystals) | 27 | 7.00 | .68 | 7.0 | .0 | 6.96 |

| Synovial biopsy | 26 | 9.08 | .56 | 9.0 | .0 | 8.89 |

| Sural nerve biopsy | 25 | 9.48 | .51 | 9.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Muscle biopsy | 25 | 8.96 | .89 | 9.0 | .0 | 8.00 |

| Bone biopsy | 25 | 9.36 | .64 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 10.00 |

| Skin biopsy | 27 | 7.44 | 1.01 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 6.88 |

| Subcutaneous fat biopsy | 25 | 7.48 | .92 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 7.46 |

| Saliva gland biopsy | 27 | 7.93 | 1.14 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 6.83 |

| Temporal artery biopsy | 25 | 9.36 | .49 | 9.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Musculoskeletal ultrasound scan | 26 | 7.85 | .46 | 8.0 | .0 | 7.91 |

| Capillaroscopy | 27 | 7.19 | .48 | 7.0 | .0 | 7.20 |

| Bone densitometry | 27 | 6.04 | .71 | 6.0 | .0 | 6.07 |

| Carotid ultrasound scan | 25 | 7.92 | .57 | 8.0 | .0 | 8.00 |

| Therapeutic techniques | ||||||

| Arthrocentesis and intra-articular injection | 27 | 6.48 | .85 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 6.50 |

| Ultrasound guided intra-articular injection | 27 | 7.74 | .66 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 7.86 |

| Radioscopically guided intra-articular injection | 24 | 8.21 | .72 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 8.20 |

| Soft tissue infiltration (tendon, ligament, fascia or muscle) | 27 | 5.85 | .91 | 6.0 | .0 | 5.84 |

| Lumbar epidural injection | 25 | 8.48 | .77 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 8.18 |

| Cervical epidural injection | 25 | 9.24 | .52 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 8.00 |

| Radioscopically guided lumbar injection | 25 | 9.00 | .76 | 9.0 | .0 | 9.00 |

| Radioscopically guided sacroiliac injection | 25 | 9.00 | .65 | 9.0 | .0 | 9.00 |

| Intra-articular injection, arthrocentesis or paediatric infiltration with sedation | 25 | 9.16 | .62 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 9.10 |

| Peripheral nerve blockage | 25 | 8.36 | .70 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 8.13 |

| Radiosynovectomy without radioscopic control (knee) | 26 | 8.04 | .87 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 7.83 |

| Radiosynovectomy with radioscopic or ultrasound control | 25 | 8.60 | .76 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 9.00 |

| Injection of intra-articular biological implants | 24 | 7.25 | .90 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 7.30 |

| Treatment of soft tissue injuries. Immobilisation | 26 | 6.46 | .86 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 6.60 |

| Ultrasound guided calcification washing | 24 | 8.46 | .51 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 8.40 |

| PRP treatment with ultrasound-guided extraction and centrifuging | 23 | 8.00 | .67 | 8.0 | .0 | – |

| Reports | ||||||

| Clinical disability report | 27 | 7.81 | .68 | 8.0 | .5 | – |

| Expert report | 27 | 8.96 | .59 | 9.0 | .0 | – |

| Overall | 27 | .75 | .8 | |||

SD: standard deviation; PRP: platelet-rich plasma; IQR: interquartile range [percentile25-percentile75].

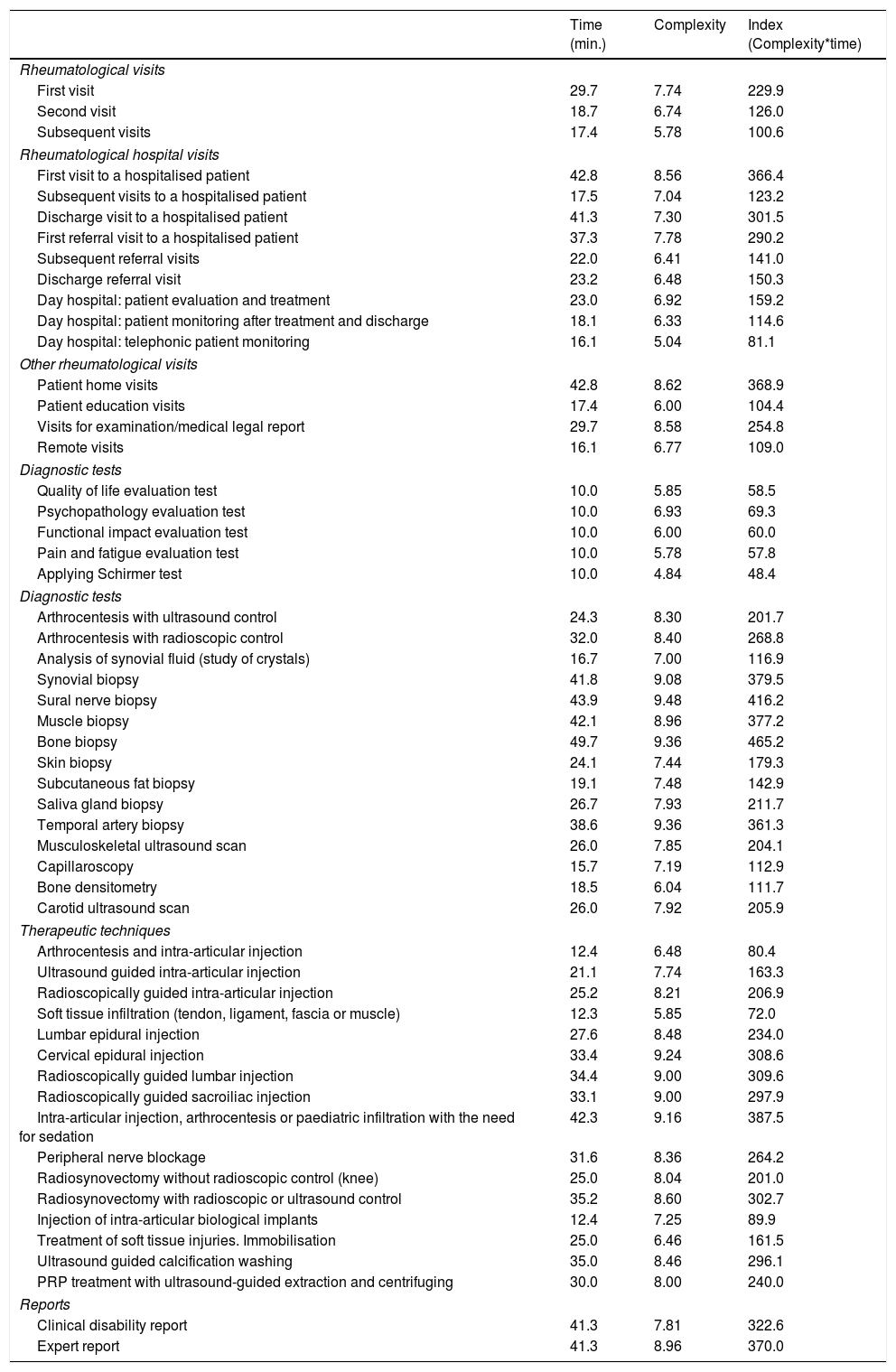

The interventions that were evaluated scored from 48 to 465 points for complexity. When they were classified according to the type of intervention (consultation, diagnosis and therapeutic), the consultations which scored the highest were the first visit to a hospitalised patient (366) and home visits (369).

Biopsies scored the highest for diagnostic techniques: bone (465), sural nerve (416) and synovial (380) biopsy. Ultrasound scans scored 204, capillaroscopy 113 and densitometry 112.

Of the therapeutic techniques, intra-articular injection/arthrocentesis/infiltration in children under sedation all scored 388 for complexity, while ultrasound scan-controlled intra-articular injection scored 163. A clinical report of disability was agreed to score 323 on the index, and an expert report 370. The complexity index for all of the interventions evaluated is shown in Table 3.

Complexity of medical, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in rheumatology.

| Time (min.) | Complexity | Index (Complexity*time) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatological visits | |||

| First visit | 29.7 | 7.74 | 229.9 |

| Second visit | 18.7 | 6.74 | 126.0 |

| Subsequent visits | 17.4 | 5.78 | 100.6 |

| Rheumatological hospital visits | |||

| First visit to a hospitalised patient | 42.8 | 8.56 | 366.4 |

| Subsequent visits to a hospitalised patient | 17.5 | 7.04 | 123.2 |

| Discharge visit to a hospitalised patient | 41.3 | 7.30 | 301.5 |

| First referral visit to a hospitalised patient | 37.3 | 7.78 | 290.2 |

| Subsequent referral visits | 22.0 | 6.41 | 141.0 |

| Discharge referral visit | 23.2 | 6.48 | 150.3 |

| Day hospital: patient evaluation and treatment | 23.0 | 6.92 | 159.2 |

| Day hospital: patient monitoring after treatment and discharge | 18.1 | 6.33 | 114.6 |

| Day hospital: telephonic patient monitoring | 16.1 | 5.04 | 81.1 |

| Other rheumatological visits | |||

| Patient home visits | 42.8 | 8.62 | 368.9 |

| Patient education visits | 17.4 | 6.00 | 104.4 |

| Visits for examination/medical legal report | 29.7 | 8.58 | 254.8 |

| Remote visits | 16.1 | 6.77 | 109.0 |

| Diagnostic tests | |||

| Quality of life evaluation test | 10.0 | 5.85 | 58.5 |

| Psychopathology evaluation test | 10.0 | 6.93 | 69.3 |

| Functional impact evaluation test | 10.0 | 6.00 | 60.0 |

| Pain and fatigue evaluation test | 10.0 | 5.78 | 57.8 |

| Applying Schirmer test | 10.0 | 4.84 | 48.4 |

| Diagnostic tests | |||

| Arthrocentesis with ultrasound control | 24.3 | 8.30 | 201.7 |

| Arthrocentesis with radioscopic control | 32.0 | 8.40 | 268.8 |

| Analysis of synovial fluid (study of crystals) | 16.7 | 7.00 | 116.9 |

| Synovial biopsy | 41.8 | 9.08 | 379.5 |

| Sural nerve biopsy | 43.9 | 9.48 | 416.2 |

| Muscle biopsy | 42.1 | 8.96 | 377.2 |

| Bone biopsy | 49.7 | 9.36 | 465.2 |

| Skin biopsy | 24.1 | 7.44 | 179.3 |

| Subcutaneous fat biopsy | 19.1 | 7.48 | 142.9 |

| Saliva gland biopsy | 26.7 | 7.93 | 211.7 |

| Temporal artery biopsy | 38.6 | 9.36 | 361.3 |

| Musculoskeletal ultrasound scan | 26.0 | 7.85 | 204.1 |

| Capillaroscopy | 15.7 | 7.19 | 112.9 |

| Bone densitometry | 18.5 | 6.04 | 111.7 |

| Carotid ultrasound scan | 26.0 | 7.92 | 205.9 |

| Therapeutic techniques | |||

| Arthrocentesis and intra-articular injection | 12.4 | 6.48 | 80.4 |

| Ultrasound guided intra-articular injection | 21.1 | 7.74 | 163.3 |

| Radioscopically guided intra-articular injection | 25.2 | 8.21 | 206.9 |

| Soft tissue infiltration (tendon, ligament, fascia or muscle) | 12.3 | 5.85 | 72.0 |

| Lumbar epidural injection | 27.6 | 8.48 | 234.0 |

| Cervical epidural injection | 33.4 | 9.24 | 308.6 |

| Radioscopically guided lumbar injection | 34.4 | 9.00 | 309.6 |

| Radioscopically guided sacroiliac injection | 33.1 | 9.00 | 297.9 |

| Intra-articular injection, arthrocentesis or paediatric infiltration with the need for sedation | 42.3 | 9.16 | 387.5 |

| Peripheral nerve blockage | 31.6 | 8.36 | 264.2 |

| Radiosynovectomy without radioscopic control (knee) | 25.0 | 8.04 | 201.0 |

| Radiosynovectomy with radioscopic or ultrasound control | 35.2 | 8.60 | 302.7 |

| Injection of intra-articular biological implants | 12.4 | 7.25 | 89.9 |

| Treatment of soft tissue injuries. Immobilisation | 25.0 | 6.46 | 161.5 |

| Ultrasound guided calcification washing | 35.0 | 8.46 | 296.1 |

| PRP treatment with ultrasound-guided extraction and centrifuging | 30.0 | 8.00 | 240.0 |

| Reports | |||

| Clinical disability report | 41.3 | 7.81 | 322.6 |

| Expert report | 41.3 | 8.96 | 370.0 |

PRP: platelet-rich plasma.

* Likert scale distribution grouped as % of disagreement (1 and 2), % of indifferent (3) and % of agreement (4 and 5).

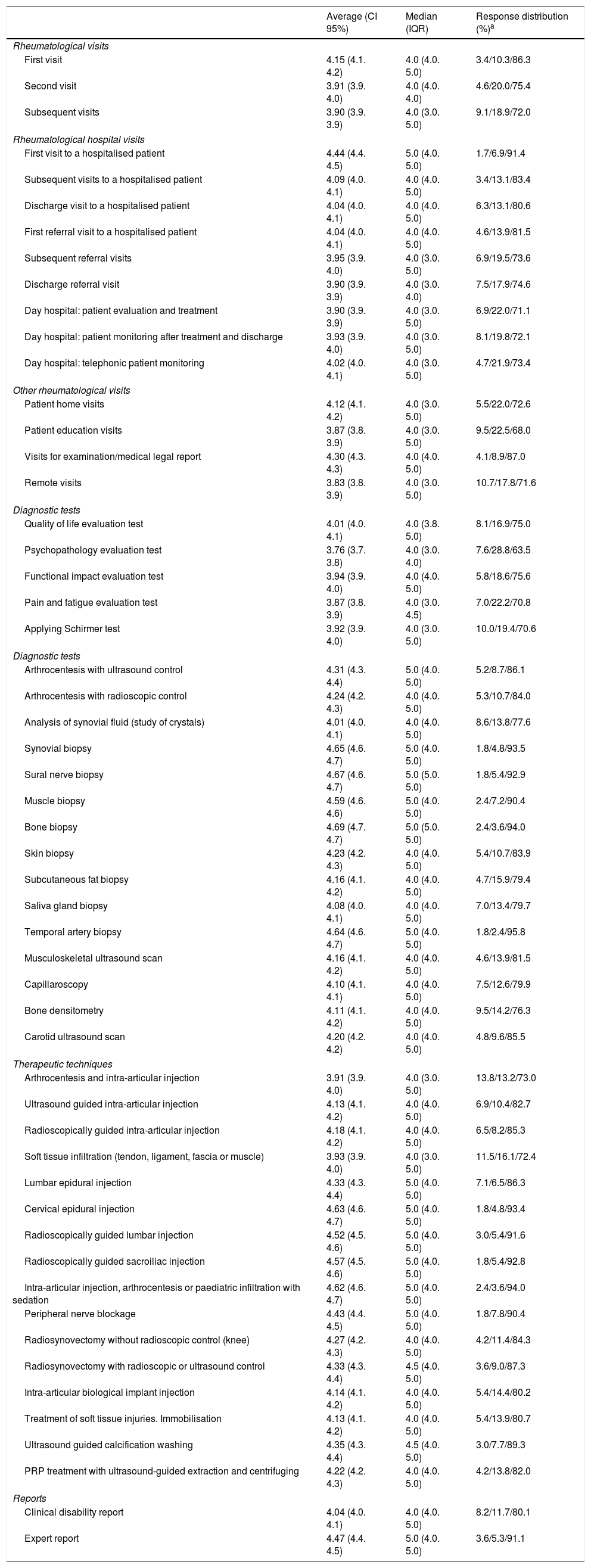

The complexity index was sent to a total of 1144 rheumatologists for validation; 175 answered, so that the response rate amounted to 15.3%. At least 70% of the respondents agreed or agreed strongly with the complexity index obtained for each intervention. The validation results are shown in Table 4.

Validation of the complexity index.

| Average (CI 95%) | Median (IQR) | Response distribution (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatological visits | |||

| First visit | 4.15 (4.1. 4.2) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 3.4/10.3/86.3 |

| Second visit | 3.91 (3.9. 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0. 4.0) | 4.6/20.0/75.4 |

| Subsequent visits | 3.90 (3.9. 3.9) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 9.1/18.9/72.0 |

| Rheumatological hospital visits | |||

| First visit to a hospitalised patient | 4.44 (4.4. 4.5) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 1.7/6.9/91.4 |

| Subsequent visits to a hospitalised patient | 4.09 (4.0. 4.1) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 3.4/13.1/83.4 |

| Discharge visit to a hospitalised patient | 4.04 (4.0. 4.1) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 6.3/13.1/80.6 |

| First referral visit to a hospitalised patient | 4.04 (4.0. 4.1) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 4.6/13.9/81.5 |

| Subsequent referral visits | 3.95 (3.9. 4.0) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 6.9/19.5/73.6 |

| Discharge referral visit | 3.90 (3.9. 3.9) | 4.0 (3.0. 4.0) | 7.5/17.9/74.6 |

| Day hospital: patient evaluation and treatment | 3.90 (3.9. 3.9) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 6.9/22.0/71.1 |

| Day hospital: patient monitoring after treatment and discharge | 3.93 (3.9. 4.0) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 8.1/19.8/72.1 |

| Day hospital: telephonic patient monitoring | 4.02 (4.0. 4.1) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 4.7/21.9/73.4 |

| Other rheumatological visits | |||

| Patient home visits | 4.12 (4.1. 4.2) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 5.5/22.0/72.6 |

| Patient education visits | 3.87 (3.8. 3.9) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 9.5/22.5/68.0 |

| Visits for examination/medical legal report | 4.30 (4.3. 4.3) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 4.1/8.9/87.0 |

| Remote visits | 3.83 (3.8. 3.9) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 10.7/17.8/71.6 |

| Diagnostic tests | |||

| Quality of life evaluation test | 4.01 (4.0. 4.1) | 4.0 (3.8. 5.0) | 8.1/16.9/75.0 |

| Psychopathology evaluation test | 3.76 (3.7. 3.8) | 4.0 (3.0. 4.0) | 7.6/28.8/63.5 |

| Functional impact evaluation test | 3.94 (3.9. 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 5.8/18.6/75.6 |

| Pain and fatigue evaluation test | 3.87 (3.8. 3.9) | 4.0 (3.0. 4.5) | 7.0/22.2/70.8 |

| Applying Schirmer test | 3.92 (3.9. 4.0) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 10.0/19.4/70.6 |

| Diagnostic tests | |||

| Arthrocentesis with ultrasound control | 4.31 (4.3. 4.4) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 5.2/8.7/86.1 |

| Arthrocentesis with radioscopic control | 4.24 (4.2. 4.3) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 5.3/10.7/84.0 |

| Analysis of synovial fluid (study of crystals) | 4.01 (4.0. 4.1) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 8.6/13.8/77.6 |

| Synovial biopsy | 4.65 (4.6. 4.7) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 1.8/4.8/93.5 |

| Sural nerve biopsy | 4.67 (4.6. 4.7) | 5.0 (5.0. 5.0) | 1.8/5.4/92.9 |

| Muscle biopsy | 4.59 (4.6. 4.6) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 2.4/7.2/90.4 |

| Bone biopsy | 4.69 (4.7. 4.7) | 5.0 (5.0. 5.0) | 2.4/3.6/94.0 |

| Skin biopsy | 4.23 (4.2. 4.3) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 5.4/10.7/83.9 |

| Subcutaneous fat biopsy | 4.16 (4.1. 4.2) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 4.7/15.9/79.4 |

| Saliva gland biopsy | 4.08 (4.0. 4.1) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 7.0/13.4/79.7 |

| Temporal artery biopsy | 4.64 (4.6. 4.7) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 1.8/2.4/95.8 |

| Musculoskeletal ultrasound scan | 4.16 (4.1. 4.2) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 4.6/13.9/81.5 |

| Capillaroscopy | 4.10 (4.1. 4.1) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 7.5/12.6/79.9 |

| Bone densitometry | 4.11 (4.1. 4.2) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 9.5/14.2/76.3 |

| Carotid ultrasound scan | 4.20 (4.2. 4.2) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 4.8/9.6/85.5 |

| Therapeutic techniques | |||

| Arthrocentesis and intra-articular injection | 3.91 (3.9. 4.0) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 13.8/13.2/73.0 |

| Ultrasound guided intra-articular injection | 4.13 (4.1. 4.2) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 6.9/10.4/82.7 |

| Radioscopically guided intra-articular injection | 4.18 (4.1. 4.2) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 6.5/8.2/85.3 |

| Soft tissue infiltration (tendon, ligament, fascia or muscle) | 3.93 (3.9. 4.0) | 4.0 (3.0. 5.0) | 11.5/16.1/72.4 |

| Lumbar epidural injection | 4.33 (4.3. 4.4) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 7.1/6.5/86.3 |

| Cervical epidural injection | 4.63 (4.6. 4.7) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 1.8/4.8/93.4 |

| Radioscopically guided lumbar injection | 4.52 (4.5. 4.6) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 3.0/5.4/91.6 |

| Radioscopically guided sacroiliac injection | 4.57 (4.5. 4.6) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 1.8/5.4/92.8 |

| Intra-articular injection, arthrocentesis or paediatric infiltration with sedation | 4.62 (4.6. 4.7) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 2.4/3.6/94.0 |

| Peripheral nerve blockage | 4.43 (4.4. 4.5) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 1.8/7.8/90.4 |

| Radiosynovectomy without radioscopic control (knee) | 4.27 (4.2. 4.3) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 4.2/11.4/84.3 |

| Radiosynovectomy with radioscopic or ultrasound control | 4.33 (4.3. 4.4) | 4.5 (4.0. 5.0) | 3.6/9.0/87.3 |

| Intra-articular biological implant injection | 4.14 (4.1. 4.2) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 5.4/14.4/80.2 |

| Treatment of soft tissue injuries. Immobilisation | 4.13 (4.1. 4.2) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 5.4/13.9/80.7 |

| Ultrasound guided calcification washing | 4.35 (4.3. 4.4) | 4.5 (4.0. 5.0) | 3.0/7.7/89.3 |

| PRP treatment with ultrasound-guided extraction and centrifuging | 4.22 (4.2. 4.3) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 4.2/13.8/82.0 |

| Reports | |||

| Clinical disability report | 4.04 (4.0. 4.1) | 4.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 8.2/11.7/80.1 |

| Expert report | 4.47 (4.4. 4.5) | 5.0 (4.0. 5.0) | 3.6/5.3/91.1 |

CI: confidence interval; PRP: platelet-rich plasma; IQR: interquartile range.

This work made is possible to prepare an updated ranked nomenclature of the 54 medical procedures undertaken by Spanish rheumatologists in their habitual clinical practice.

The reference criterion for the whole state is the one approved by the Organización Médica Colegial,2 with data from the year 2003. This only includes 20 procedures, of which 4 are hospital visits on different days after admission. This criterion contains no more than half of the interventions which are intrinsic to rheumatology. Individually, each hospital and each insurance company applies a different list of care interventions, and these lists vary widely.

Caring for patients with systemic or inflammatory pathology requires the quantification of outcome assessments to establish treatment strategies, in the search for a therapeutic objective. For decades, patient perception of their own health and how disease affects different areas of their life has been taken into account in evaluating quality of life. It is also used as a disease activity parameter. These assessments are obtained in part from questionnaires completed by patients, which are routinely applied in medical departments (Patient Reported Outcomes). Their use and application are considered to be indispensible for the standardised quantification of working in many pathologies.5–7 This is also the case for therapeutic decision-making and measuring the results of clinical trials, so that they have to be included as tasks which are intrinsic to the speciality. Depending on whether they consist of evaluations of quality of life, psychopathological factors, functional impact or pain, their complexity index is said to stand at from 58.5 to 69.3.

In recent decades rheumatology has seen exponential progress in new treatments. The administration of intravenous therapies such as bisphosphonates in metabolic bone diseases, biological therapies in systemic or inflammatory diseases and intravenous immunoglobulin or cyclophosphamide all form part of the usual routine in contemporary rheumatology. Due to the need to administer these drugs, rheumatology departments began to include day hospital care departments, and this is now habitual. They also include the administration of diagnostic or therapeutic techniques, as well as support for clinical trials. 77.7% of rheumatologists have a day hospital (unpublished SER data). In the VALORA study, 91% of Day Hospital Units use integrated visits that cover clinical evaluation, analysis and procedures. The average number of treatments carried out in these units by rheumatology amounted to 748.3, while it totalled 1126.73 in complex hospitals.8 It was found that work in these units should be updated and included within our nomenclature, and it was evaluated with a resulting complexity index of from 159 to 114, depending on whether it was the first or a post-treatment visit.

Rheumatology has progressed thanks to the inclusion of new treatments, and another major revolution has occurred in the use of new diagnostic and therapeutic tools and techniques such as capillaroscopy, which are intrinsic to the speciality and in widespread use. In fact, 72.1% of rheumatologists have direct access to this technique (unpublished SER data) together with, and more recently, ultrasound scan imaging.

Ultrasound imaging really has become a highly useful complementary form of examination for rheumatologists. It permits the harmless, static and dynamic evaluation of joint, muscle, tendon and ligament pathologies, as well as compression and vascular neuropathies. Given its usefulness, the SER founded an ultrasound imaging school in 1996. This has a teaching staff of 28 experts, and they have taught 420 courses to date, training more than 1000 rheumatologists. 71.7% of rheumatologists had their own ultrasound scan device in 2014 (unpublished SER data). Ultrasound imaging has attained a position of honour in the current nomenclature of the speciality. It is an effective diagnostic tool as it offers a good approximate view of lesion anatomy and inflammatory activity by using a scale of greys9 and the Doppler signal,10,11 respectively. It is a technique that supports other imaging tests for ultrasound-guided intra-articular contrast injection. For treatment, the spread of ultrasound imaging has led rheumatologists to adopt new interventionist techniques that can be undertaken with greater precision. These include blockages, arthrocentesis or infiltrations and ultrasound-guided treatments. These processes were graded with a complexity index of up to 387, in the case of paediatric joint puncture with sedation.

Although some techniques such as synovial, nerve, saliva gland, temporal artery or bone biopsy are not exclusive to rheumatologists, it should not be forgotten that they are habitually performed in some rheumatology units. Nor should it be forgotten that in other rheumatology units, rheumatologists themselves control pain by using more specific interventionist techniques such as epidural infiltrations.12 The interventionist techniques defined as the most complex were biopsies, particularly bone biopsy.

Densitometry has been validated as a bone density quantification technique13 and its result may form part of the international indexes used to calculate the risk of fracture.14 Rheumatologists perform this test or evaluate its results regularly in their work for the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. In fact, 20% of rheumatology departments have their own densitometer (unpublished SER data) so that we agree that they should be present in all lists of medical procedures concerning our speciality, with a complexity rating somewhat higher than that of a successive visit (111 vs 100).

Rheumatic diseases are one of the main causes of disability and disease burden worldwide. Data on the impact of musculoskeletal diseases on health indicate that almost 1 in 4 Spanish people have a rheumatic disease; neck pain and lumbago were the chief causes of disability in Spain in 2016.15,16 This justifies the frequency with which rheumatologists are asked for reports in their clinical practice that officially justify some type of disability or handicap. Moreover, rheumatologists may intervene as experts or prepare special expert reports as a part of their work outside care. Such reports were evaluated as having a complexity index of 322 and 370.

This work supplies the first ranked and agreed nomenclature of a medical speciality undertaken by a state scientific society. A tool has been constructed to improve patient care and minimise geographical variations in all areas of care.

FinancingThis work was financed by the Sociedad Española de Reumatología from the assignment for Services to Members and Private Practice.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank the panel of experts (Dr. Susana Gerechter, Dr. Juan Carlos Duró, Dr. Antonio Gómez Centeno, Dr. María Rocío González, Dr. Javier Calvo Catalá, Dr. José Ivorra, Dr. Rosa Roselló, Dr. Manuel Tenorio, Dr. Paloma Vela, Dr. Encarna Pagán, Dr. Montserrat Romera, Dr. Manuel Acasuso, Dr. Georgina Salvador, Dr. Ana Urruticoechea, Dr. Marta Larrosa, Dr. Mónica Vázquez, Dr. Cayetano Alegre, Dr. José Luis Guerra, Dr. Ana Cruz Valenciano, Dr. Emilio Martín Mola, Dr. Jesús Tornero, Dr. Javier del Pino, Dr. Julio Medina, Dr. José Manuel Rodríguez Heredia, Dr. Eugenio Chamizo, Dr. Miguel Ángel Abad, Dr. María Luz García Vivar, Dr. Santiago Muñoz Fernández, Dr. Sara Manrique Arija and Dr. María Alcalde) for their collaboration in this project, together with all of the SER staff for their professionalism and dedication.

Please cite this article as: Yoldi Muñoz B, Martín Martínez MA, Valero Expósito M, Plana Veret C, Andreu Sánchez JL, Moreno Muelas JV. Nomenclátor jerarquizado en reumatología. Reumatol Clin. 2020;16:3–10.