We describe a case of a male patient with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and lupus nephritis. A patient who was initially diagnosed with multibacillary leprosy, an infectious disease, with clinical symptoms for two years. However, after hospitalization and investigation, his diagnosis was revoked and replaced with SLE. The aim of this study is to emphasize the importance of knowing the most important and significant clinical changes in SLE and thus allowing an accurate diagnosis, preventing disease progression with target organ involvement, and allowing better clinical management.

Describimos el caso de un varón con lupus eritematoso sistémico y nefritis lúpica. Se trata de un paciente con diagnóstico inicial de lepra multibacilar, una enfermedad infecciosa con síntomas clínicos desde hacía 2 años. Sin embargo, tras su hospitalización e investigación, se revocó dicho diagnóstico, sustituyéndose por lupus eritematoso sistémico. El objetivo de este estudio es resaltar la importancia de conocer los cambios clínicos más importantes y significativos del lupus eritematoso sistémico, permitiendo así su diagnóstico preciso y previniendo la progresión de la enfermedad con compromiso de órganos diana, así como un mejor manejo clínico.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a rare, chronic inflammatory disease of connective tissue, of an autoimmune nature and whose pathogenesis is heterogeneous, generally characterized by the deposition of immune complexes and production of autoantibodies.1 The clinical presentation of SLE is variable and can affect any organ, singly or cumulatively, at any age. As its clinical status is variable and sometimes nonspecific, the diagnosis can be delayed and patients are often treated for conditions other than SLE.2,3 In the literature there are already descriptions of several cases of SLE that mimic leprosy and vice versa,4–10 although it is still difficult to establish the prevalence of these conditions given that patients can spend a lot of time treating diseases with incorrect diagnosis.

Clinical observationPatient, male, 33 years old, admitted in hospital due to adverse reaction to treatment for multibacillary leprosy (dapsone) after less than 1 month of use and presence of difficult-to-heal ulcers in lower limbs for 2 years, even with previous antibiotic therapy. Diagnosis of multibacillary leprosy through February/2022 biopsy, consistent with erythema nodosum leprosum with scar areas and negative AFB test. Previous pathology reported treatment for tertiary syphilis 3 years ago, without other comorbidities. On admission, evaluated by a dermatologist, who questioned the initial diagnosis, however, he advised the use of empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy, suspension of treatment for leprosy, request markers for SLE and activity of rheumatologic disease, in addition to the evaluation of rheumatology for a possible diagnosis of lupus.

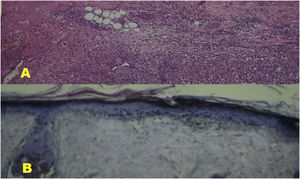

In the rheumatological evaluation, he had the criteria of non-scarring alopecia, discoid lupus, photosensitivity, hemolytic anemia, leukopenia and pericardial effusion on echocardiography. As for the results of the rheumatological markers, they demonstrated, through indirect immunofluorescence, an ANA fine speckled nuclear pattern (AC-4) greater than 1/640 and ANTI-dsDNA 1/10; through the enzyme-immunoassay method, an Anti-SSA of 49.7U (positive), anticardiolipin IGG of 34.3 GPL (positive) and anticardiolipin IGM of 145.5 MPL (positive); the lupus anticoagulant, through the coagulometric method, was also positive with 1.22; and through turbidimetry, a reduction in serum complement proteins C3 and C4 was also evidenced, with 35mg/dL and <8mg/dL, respectively. Thus scoring 28 points by the EULAR/ACR-2019 criteria. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis established for lupus, as well as the result of a new biopsy (scalp) compatible with lupus erythematosus (comparative between first and second biopsy in Fig. 1). The SELENA-SLEDAI criteria were used to initiate immunosuppressive therapy, which considered vasculitis in the lower limbs (ulcers without healing for 2 years), 24-h proteinuria greater than 0.5g, alopecia, hypocomplementemia, leukopenia, fever, scoring 19 and characterizing severe disease activity. Opted for pulse therapy 3:1 for 6 months, with 3 days of methylprednisolone followed by 1 day of cyclophosphamide. Patient was later discharged with prescription of hydroxychloroquine, prednisone, folic acid, acetylsalicylic acid, vitamin and mineral supplementation and follow-up with rheumatology, infectiology and ophthalmology. After 1 month, the patient returned for evaluation with a rheumatologist and presented with improvement of the vasculitis lesions, although still without complete healing and maintained normal renal function values. However, he maintained the same values of proteinuria in the follow-up after one month: proteinuria>0.5g/24h. After 1 month, the patient was referred to another reference unit for his own interest, as this other unit was closer to where he lived.

(A) Histological section of the lateral foot (scar area) revealing small vessel vasculitis associated with areas of scarring fibrosis and dystrophic calcification. There are no alcohol-acid-resistant bacilli. Compatible with erythema nodosum leprosum with scar areas. (B) Histological section of the scalp region revealing mild hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, ballooning of basal keratinocytes and discrete perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Compatible with lupus erythematosus.

Some forms of leprosy, such as lepromatous and borderline leprosy, may present with serological alterations and clinical alterations that are also consistent with other rheumatic pathologies, mainly rheumatoid arthritis and SLE.8–10 Among the most common serological abnormalities we have rheumatoid factor (which may even be present in population without disease), ANA, anti-DNA and anticardiolipin antibody.6,7 Clinical changes involve erythema nodosum and vasculitis, skin changes that are very common in leprosy and which should be considered by health professionals, especially in regions where this disease is endemic. Other similar clinical manifestations between the two conditions can also occur such as livedo reticularis, malar rash, skin thickening, Raynaud's phenomenon, oral ulcers and even glomerulonephritis.8–11 There are several goals when developing a treatment plan for the patient with SLE: reducing disease activity (induction of remission), preventing exacerbations, treating them when they occur, and decreasing damage to organs and systems, as well as complications of the disease. disease and treatment.3,11 Among the drugs available today, corticosteroids and immunosuppressants are generally used, which protect the organs from the inflammatory aggression caused by disorders in the immune system and induce remission of the disease, but do not prevent or reverse the initial failure of the system.12–14 Just as the diagnostic criteria allowed greater sensitivity to detect those affected by SLE, some criteria were also developed to identify disease activity, such as the SLEDAI (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index), widely used and reproducible in Brazil.15,16

ConclusionAlthough less frequent in men, the diagnostic hypothesis of SLE should always be considered in patients with a chronic history of conditions without clinical improvement even after undergoing various therapies. The case presented reveals that, even showing typical changes for the disease with photosensitivity, non-scarring alopecia and discoid lupus for more than 2 years, the diagnosis of the disease was initially wrong, requiring even a biopsy.

InformationConsent was obtained for experimentation with human subjects.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.