lupus nephritis represents a challenge in treatment. In spite of intensive therapy, is common a sustained renal incomplete response.

ObjectiveTo describe different responses to adequate/intensive treatment to lupus nephritis.

MethodsObservational retrospective study, including Mexican>18 years old patients with lupus nephritis who visited tertiary rheumatology centers in several urban cities in Mexico. SLE was diagnosed according to 1997 ACR. The exclusion criteria were follow-up<6 months and reduced GFR due to other comorbidities such as diabetes or other primary renal disease.

ResultsWe included 193 patients with a mean age of 34 years, 80% were women. Biopsy was available in 166 patients (86%): class IV in 42%, class III in 23%, the mean of activity and chronicity index were 6.4 and 2.6 respectively; class V represented 10.2%. The least frequent class was Class II (9%), and mixed classes (III or IV+V) accounted for 11%.

Cyclophosphamide (CYC) was used in 146 patients (76.6%), mycophenolate (MMF) in 144 and tacrolimus (TCR) in 28. In most cases, were used combination therapy.

Only 38 patients had a follow-up of less than 1 year; 16 (42%) had CR, 13 (34%) had NR, and 9 (23%) PR. 55% of patients with PR received a multitarget protocol, 75% of CR received the NIH protocol, and 61.5% of NR the NIH protocol.

Of patients followed up for more than a year (155), 35% had persistently inactive response, 24.5% were relapsing–remitting, 20% were chronically active, and 20% showed a mixed pattern.

ConclusionsPrevalence of persistent or intermittent activity patterns was high (64.5%). Most Mexican rheumatologists switched to more intensive treatment, adding a second or third drug.

la nefritis lúpica representa un gran reto de tratamiento. A pesar de terapia intensa es común la respuesta incompleta.

Objetivodescribir diferentes tipos de respuestas a tratamiento adecuado/intenso para nefritis lúpica, a 1 año y posterior al año de seguimiento.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo observacional, de pacientes mexicanos>18 años, con nefritis lúpica, atendidos en centros terciarios de atención reumatológica. El diagnóstico de lupus de acuerdo a criterios del ACR 1997. Criterios de exclusión fueron seguimiento<6 meses y daño renal por otras comorbilidades como diabetes u otra enfermedad renal primaria.

Resultadosincluimos 193 pacientes con edad promedio de 34 años, 80% mujeres. La biopsia renal disponible en 166 (86%): clase IV 42%, III 23%, con actividad y cronicidad de 6.4 y 2.6 respectivamente, clase V 10.2% y mixtas 11%; la menos frecuente la clase II en 9%.

Ciclofosfamida se empleó en 146 pacientes (76.6%), micofenolato en 144 y tacrolimus en 28; la mayoría de los pacientes recibieron terapia combinada.

Sólo 38 tuvieron menos de 1 año de seguimiento; 16 (42%) tuvieron remisión completa, 9 (23%) parcial y 13 (34%) sin respuesta. El 75% con RC y 61.5% NR con terapia como protocolo NIH; 55% de aquellos con RP recibieron terapia combinada.

Pacientes seguidos por más de 1 año (155), 35% persistentemente tuvieron respuesta, 24.5% cursaron con remisiones y exacerbaciones, 20% crónicamente activa y 20% patrón mixto.

Conclusionesla prevalencia de actividad persistente o intermitente fue alta (64.5%). La mayoría de los reumatólogos mexicanos decidió terapia más intensa con adición de 2 o más inmunosupresores.

Lupus nephritis affects 40–60% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, almost half of whom do not respond to initial treatment, and 20% will require renal replacement therapy.1–3

The most frequent pattern of renal activity was relapse, which was observed in 54% of these patients.4 In Hispanic ethnicity (particularly Mexican), lupus nephritis has a worse prognosis than in Asian and Caucasian populations, probably because of the inability to achieve complete renal response, poor treatment adherence, and lower sociocultural level.5

Lupus nephritis is associated with a high mortality rate. Therefore, it is important to look for new therapeutic options, such as belimumab and voclosporin, and to consider new schemes for well-known drugs, such as multitarget therapy.6–9 The clinical behavior of lupus nephritis patients in real-life settings regarding the frequency of change of therapeutic schemes is unknown, including new therapeutic schemes as well as switching diverse schemes.

This study aimed to describe the different patterns of clinical response to lupus nephritis and the different therapeutic schemes used for its induction and maintenance in several tertiary rheumatologic units in Mexico.

MethodsWe retrospectively enrolled patients with lupus nephritis who visited tertiary rheumatology centers in several urban cities in Mexico. We used the following inclusion criteria: adults (>18 years) diagnosed with lupus nephritis established through renal biopsy or UPCR>0.5, 24-h protein collection>500mg, or dysmorphic erythrocytes in urine sediment and/or renal biopsy. We used the 2012 SLICC criteria for SLE for diagnosis; the exclusion criteria were follow-up<6 months and reduced GFR due to other comorbidities such as diabetes or other primary renal disease.

Patients with less than a year of follow-up were classified according to therapeutic response as follows:

- •

Complete response (CR):

- a)

Creatinine less than 1.2mg/dL,

- b)

UPCR<0.5.

- a)

- •

Partial response (PR):

- a)

>50% reduction of baseline UPCR,

- b)

Normal creatinine levels.

- a)

- •

Non-respondents (NR): patients who failed to meet the above criteria.

Patients with follow-up>1 year were classified into one of the following patterns:

- •

Persistent inactive: Remission was achieved, and no relapse was observed during follow-up.

- •

Relapsing–remitting: More than one moderate/severe relapse after remission was observed.

- •

Mixed pattern: presence of more than two pattern during follow-up

- •

Chronically active: partial remission was achieved without recovery of GFR and had a gradual decrease in GFR of >25%, compared with the last GFR achieved in partial remission or had a UPCR>0.5, for 2 consecutive years.

The induction treatments used were the National Institutes of Health (NIH) lupus nephritis or EUROlupus protocols. We defined the multitarget step-up protocol as patients who started with either NIH or Eurolupus protocols but did not comply during the induction phase then received a new immunosuppressant during follow-up.10,11

Descriptive statistics were used for the analysis. We described the clinical, demographic, and treatment variables in patients with <1 year of follow-up and divided the patients according to whether they had partial, complete, or no response. In patients with >1 year of follow-up, we compared the same variables, but divided the patients into persistent inactive, relapsing–remitting-chronically active, or mixed patterns

ResultsWe included 193 patients with a mean age of 34 years (standard deviation [SD]=12.9); 80% were women. Biopsy was available in 166 patients (86%), the distribution of renal classification was as follows: class IV in 42%, class III in 23%, the mean of activity and chronicity index were 6.4 and 2.6 respectively; class V represented 10.2%. The least frequent class was Class II (9%). The mixed classes (III or IV+V) accounted for 11% of the total.

Regarding treatment, cyclophosphamide (CYC) was used in 146 patients (76.6%), with an accumulated dose of 6640mg; mycophenolate (MMF) was used in 144 patients and tacrolimus (TCR) in 28 patients. In most cases, these drugs were used in combination therapy: CYC+MMF 46%, CYC+MMF+TCR 10%, CYC as monotherapy 18%, and MMF as monotherapy 12%.

At baseline, the GFR was 95.8ml/min (SD 48.6), and at the end of the follow-up, it was 94.3ml/min (SD 39.5). Proteinuria at baseline was 1.7g (IQR, 2.8) and at the end of follow, 0.59g (IQR 1.8).

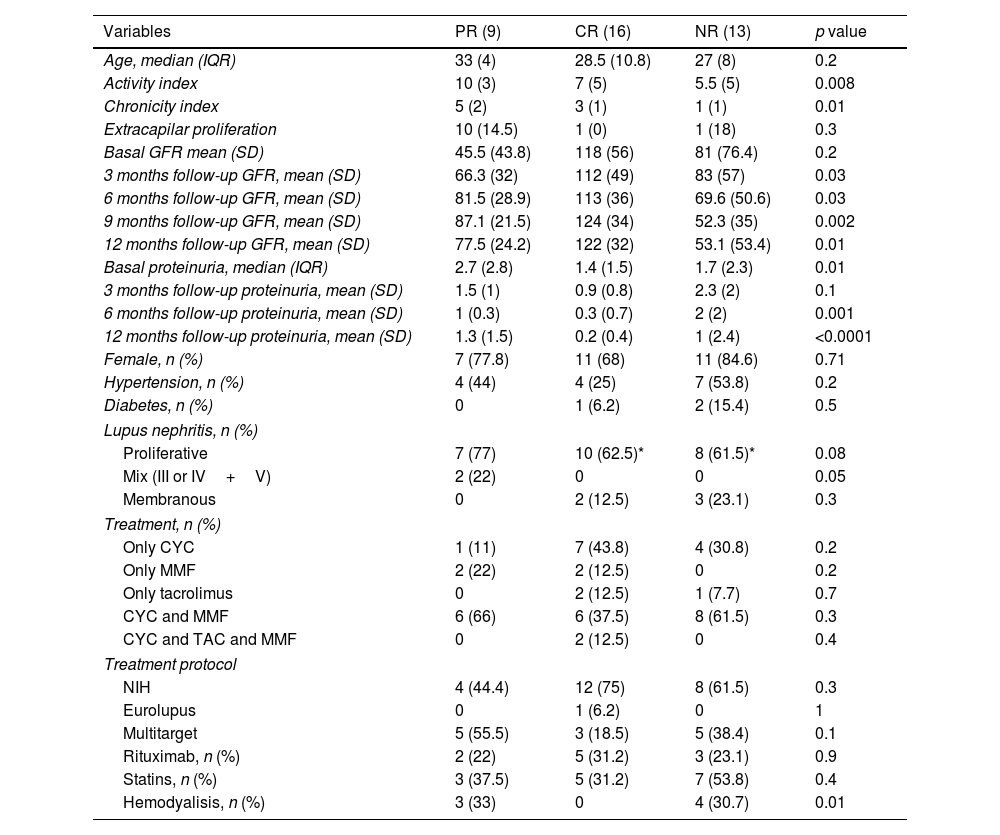

Patients with less than one year of follow-upOnly 38 patients had a follow-up of less than 1 year; 16 (42%) had complete response, 13 (34%) had no response, and 9 (23%) had partial response. In these cases, the predominant type of nephritis was proliferative. Patients with complete response had a median activity index of 7 and a chronicity index of 3.

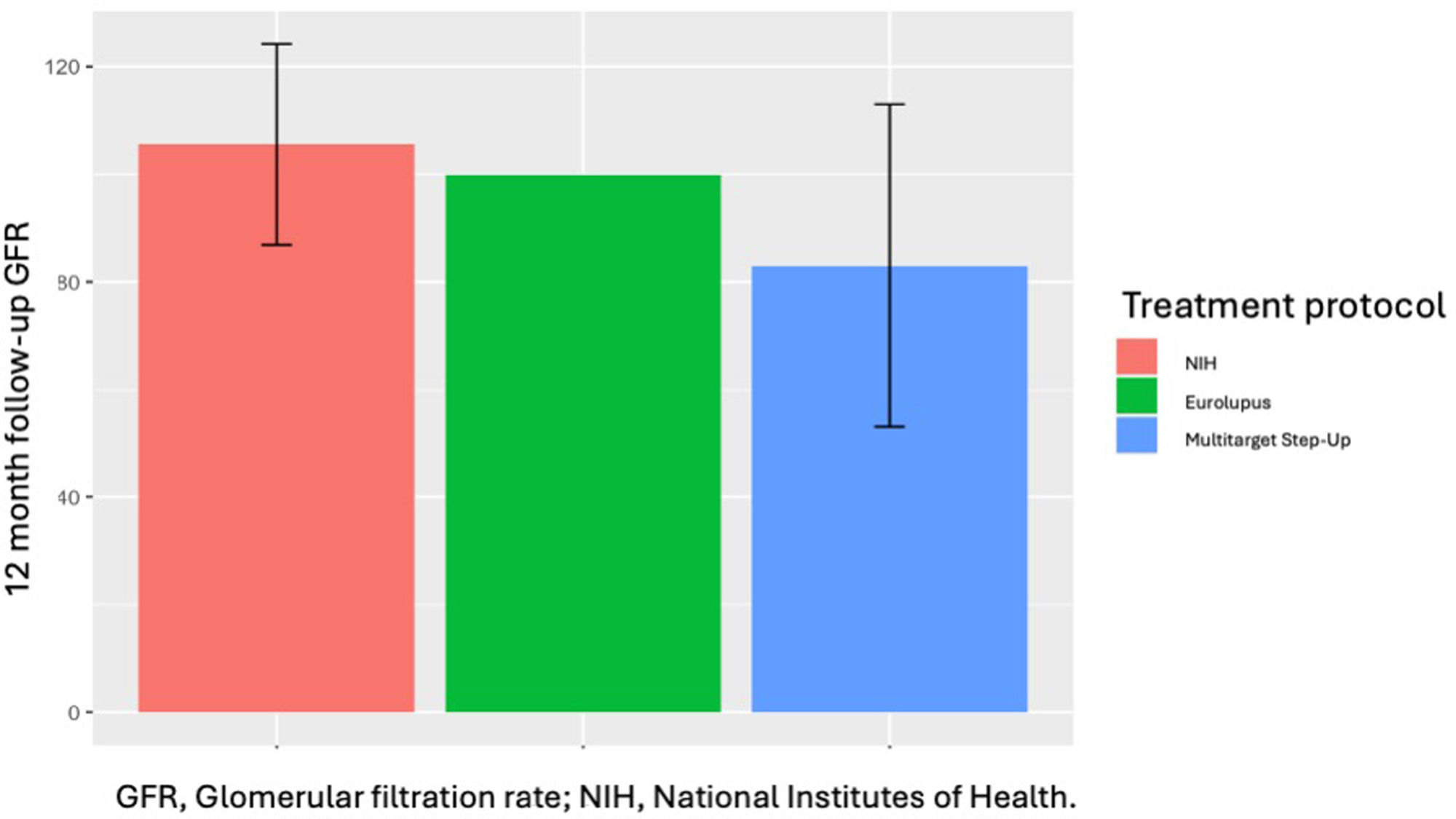

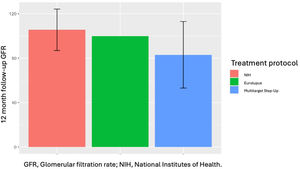

In the group that received the NIH treatment protocol, the mean glomerular filtration rate at the last visit was 100ml/m2 (SD 39.2), compared to 87ml/m2 (SD 37.9) in the non-NIH protocol (p=0.02). Regarding therapeutic responses, no significant differences were observed between NIH and no-NIH treatment protocols (Table 1).

Lupus nephritis patients with ≤1 year follow up.

| Variables | PR (9) | CR (16) | NR (13) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 33 (4) | 28.5 (10.8) | 27 (8) | 0.2 |

| Activity index | 10 (3) | 7 (5) | 5.5 (5) | 0.008 |

| Chronicity index | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.01 |

| Extracapilar proliferation | 10 (14.5) | 1 (0) | 1 (18) | 0.3 |

| Basal GFR mean (SD) | 45.5 (43.8) | 118 (56) | 81 (76.4) | 0.2 |

| 3 months follow-up GFR, mean (SD) | 66.3 (32) | 112 (49) | 83 (57) | 0.03 |

| 6 months follow-up GFR, mean (SD) | 81.5 (28.9) | 113 (36) | 69.6 (50.6) | 0.03 |

| 9 months follow-up GFR, mean (SD) | 87.1 (21.5) | 124 (34) | 52.3 (35) | 0.002 |

| 12 months follow-up GFR, mean (SD) | 77.5 (24.2) | 122 (32) | 53.1 (53.4) | 0.01 |

| Basal proteinuria, median (IQR) | 2.7 (2.8) | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.7 (2.3) | 0.01 |

| 3 months follow-up proteinuria, mean (SD) | 1.5 (1) | 0.9 (0.8) | 2.3 (2) | 0.1 |

| 6 months follow-up proteinuria, mean (SD) | 1 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.7) | 2 (2) | 0.001 |

| 12 months follow-up proteinuria, mean (SD) | 1.3 (1.5) | 0.2 (0.4) | 1 (2.4) | <0.0001 |

| Female, n (%) | 7 (77.8) | 11 (68) | 11 (84.6) | 0.71 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 4 (44) | 4 (25) | 7 (53.8) | 0.2 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0 | 1 (6.2) | 2 (15.4) | 0.5 |

| Lupus nephritis, n (%) | ||||

| Proliferative | 7 (77) | 10 (62.5)* | 8 (61.5)* | 0.08 |

| Mix (III or IV+V) | 2 (22) | 0 | 0 | 0.05 |

| Membranous | 0 | 2 (12.5) | 3 (23.1) | 0.3 |

| Treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Only CYC | 1 (11) | 7 (43.8) | 4 (30.8) | 0.2 |

| Only MMF | 2 (22) | 2 (12.5) | 0 | 0.2 |

| Only tacrolimus | 0 | 2 (12.5) | 1 (7.7) | 0.7 |

| CYC and MMF | 6 (66) | 6 (37.5) | 8 (61.5) | 0.3 |

| CYC and TAC and MMF | 0 | 2 (12.5) | 0 | 0.4 |

| Treatment protocol | ||||

| NIH | 4 (44.4) | 12 (75) | 8 (61.5) | 0.3 |

| Eurolupus | 0 | 1 (6.2) | 0 | 1 |

| Multitarget | 5 (55.5) | 3 (18.5) | 5 (38.4) | 0.1 |

| Rituximab, n (%) | 2 (22) | 5 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | 0.9 |

| Statins, n (%) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (31.2) | 7 (53.8) | 0.4 |

| Hemodyalisis, n (%) | 3 (33) | 0 | 4 (30.7) | 0.01 |

According to clinical responses, 55% of patients with partial response received a multitarget protocol, 75% of complete responders received the NIH protocol, and 61.5% of non-responders received the NIH protocol. Although most rheumatologists admittedly used the NIH treatment protocol as the initial treatment (97%), during follow-up, 34% of the same rheumatologists added mycophenolate and 11.4% added mycophenolate and tacrolimus.

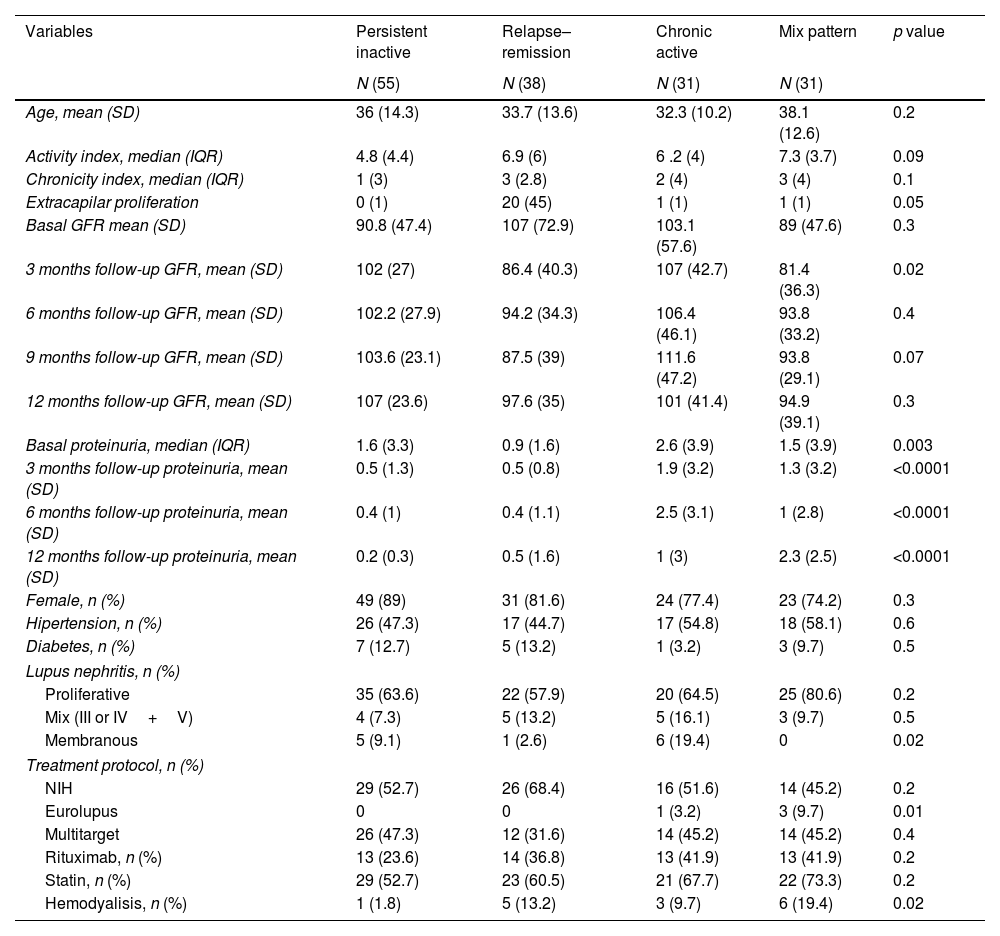

Patients with more than one year of follow-upThe remaining patients (n=155) were followed up for more than a year. The response patterns were as follows: 55 patients (35%) were persistently inactive, 38 were relapsing–remitting (24.5%), 31 (20%) were chronically active, and 31 (20%) showed a mixed pattern. The activity index was higher for relapsing–remitting patterns (6.9) and mixed patterns (7.3). Patients in the relapsing–remitting group exhibited higher extracapillary hypercellularity and crescents. The most common LN type of lupus nephritis was proliferative, with no intergroup differences (Table 2).

LN patients with more than one year of follow-up.

| Variables | Persistent inactive | Relapse–remission | Chronic active | Mix pattern | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (55) | N (38) | N (31) | N (31) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 36 (14.3) | 33.7 (13.6) | 32.3 (10.2) | 38.1 (12.6) | 0.2 |

| Activity index, median (IQR) | 4.8 (4.4) | 6.9 (6) | 6 .2 (4) | 7.3 (3.7) | 0.09 |

| Chronicity index, median (IQR) | 1 (3) | 3 (2.8) | 2 (4) | 3 (4) | 0.1 |

| Extracapilar proliferation | 0 (1) | 20 (45) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.05 |

| Basal GFR mean (SD) | 90.8 (47.4) | 107 (72.9) | 103.1 (57.6) | 89 (47.6) | 0.3 |

| 3 months follow-up GFR, mean (SD) | 102 (27) | 86.4 (40.3) | 107 (42.7) | 81.4 (36.3) | 0.02 |

| 6 months follow-up GFR, mean (SD) | 102.2 (27.9) | 94.2 (34.3) | 106.4 (46.1) | 93.8 (33.2) | 0.4 |

| 9 months follow-up GFR, mean (SD) | 103.6 (23.1) | 87.5 (39) | 111.6 (47.2) | 93.8 (29.1) | 0.07 |

| 12 months follow-up GFR, mean (SD) | 107 (23.6) | 97.6 (35) | 101 (41.4) | 94.9 (39.1) | 0.3 |

| Basal proteinuria, median (IQR) | 1.6 (3.3) | 0.9 (1.6) | 2.6 (3.9) | 1.5 (3.9) | 0.003 |

| 3 months follow-up proteinuria, mean (SD) | 0.5 (1.3) | 0.5 (0.8) | 1.9 (3.2) | 1.3 (3.2) | <0.0001 |

| 6 months follow-up proteinuria, mean (SD) | 0.4 (1) | 0.4 (1.1) | 2.5 (3.1) | 1 (2.8) | <0.0001 |

| 12 months follow-up proteinuria, mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.5 (1.6) | 1 (3) | 2.3 (2.5) | <0.0001 |

| Female, n (%) | 49 (89) | 31 (81.6) | 24 (77.4) | 23 (74.2) | 0.3 |

| Hipertension, n (%) | 26 (47.3) | 17 (44.7) | 17 (54.8) | 18 (58.1) | 0.6 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 7 (12.7) | 5 (13.2) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) | 0.5 |

| Lupus nephritis, n (%) | |||||

| Proliferative | 35 (63.6) | 22 (57.9) | 20 (64.5) | 25 (80.6) | 0.2 |

| Mix (III or IV+V) | 4 (7.3) | 5 (13.2) | 5 (16.1) | 3 (9.7) | 0.5 |

| Membranous | 5 (9.1) | 1 (2.6) | 6 (19.4) | 0 | 0.02 |

| Treatment protocol, n (%) | |||||

| NIH | 29 (52.7) | 26 (68.4) | 16 (51.6) | 14 (45.2) | 0.2 |

| Eurolupus | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) | 0.01 |

| Multitarget | 26 (47.3) | 12 (31.6) | 14 (45.2) | 14 (45.2) | 0.4 |

| Rituximab, n (%) | 13 (23.6) | 14 (36.8) | 13 (41.9) | 13 (41.9) | 0.2 |

| Statin, n (%) | 29 (52.7) | 23 (60.5) | 21 (67.7) | 22 (73.3) | 0.2 |

| Hemodyalisis, n (%) | 1 (1.8) | 5 (13.2) | 3 (9.7) | 6 (19.4) | 0.02 |

The treatment protocol was similar except for the EUROlupus protocol, which is the least common protocol (Fig. 1). In addition, there was no difference in the use of rituximab among the four groups. The proportion of patients using the multi-target step-up protocol was similar between the groups.

DiscussionWe observed a higher prevalence of persistent or intermittent activity patterns in our patients (64.5%). One-third of those with a follow-up<1 year had no response. In this group, although the initial intention was to use a specific treatment protocol, such as NIH, most rheumatologists switched to more intensive treatment by adding a second or third immunosuppressor. The real indication (whether it was due to intolerance or another issue) for this step-up treatment was not specified in the database.

In patients with >1 year follow up, the response rate was low. Only one-third had persistent inactive nephritis, and the rest behaved similarly to the group with less than a year of follow-up. Remarkably, a higher proportion of the patients in this group received rituximab. Similar findings were reported by in the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, in which they observed a mixed pattern of lupus activity was the most common one; and only a 30% had a “long quiescent” activity pattern in a 3 year follow up.4,12

The different responses to treatment protocols across sexes and races are a constant feature in systemic lupus erythematosus, which is also observed in lupus nephritis. The vast majority of lupus patients had a relapsing–remitting pattern and <5% maintained prolonged remission.13

Since the above examples focused on systemic manifestations, the main scores used to measure activity were the Physician Global Assessment, SLEDAI, and their multiple modifications. However, the main advantage of our study is that we focused on renal expression, and most of our patients received multitarget therapy; however, in spite of this combined immune-suppressive therapy the outcome in general was poor.

We must address that an important cause of persistent activity, or the presence of a relapsing–remitting pattern may be nonadherence to a specific treatment protocol, adding that unfortunately we didn’t have any data regarding adherence in this cohort. In this regard, non-adherence in patients with lupus ranges from 3 to 76%.14,15 Regardless, the response rate in our population was lower than expected, despite the use of combined or multitarget therapy.

In view of the above, we consider that Mexican patients with lupus nephritis should receive more intensive/adequate treatment for all histopathological LN classes. This recommendation should be kept in mind, with triple or at least dual immunosuppressive therapy, according with the recently published international guidelines.16–19

ConclusionThe most common scheme of treatment used in the cohort of Mexican patients in tertiary centers was the NIH, but almost half of rheumatologist added another immunosuppressor including rituximab due to partial response or no-response.

Thus, in our Mexican population, the use of combinated therapy or mulltitarget therapy, does not achieve the desired goals of complete/partial remission of lupus nephritis.

Informed consentAll patients had informed consent to realized renal biopsy.

Conflict of interestsAuthors mentioned any conflict of interest to declare.